This is the second installment of the revised and expanded 2017 edition of my regimental history of the 38th Mississippi Infantry. It will cover the regiment’s participation in the battle of Corinth and the siege of Vicksburg. This portion of the history will also detail the 38th’s reorganization after Vicksburg, and the regiment’s change into a mounted infantry unit in 1864. I hope you enjoy this portion of Beneath Torn and Tattered Flags, and please check back for the final installment of the regimental history of the 38th Mississippi, which will be posted very soon!

Chapter IIII

Redemption at Corinth

I will sum up by saying that we had to fight three days to get out of the trap old Van Dorn got us in. 1

– Lt. Col. Preston Brent on the battle of Corinth.

In camp at Baldwyn, the 38th’s soldiers finally had a chance to rest and reflect on

their failure at Iuka. Some came to the conclusion that their one glimpse of battle was enough to last a lifetime and so they quietly slipped away from camp and started home. Desertions were particularly heavy in the Hancock Rebels, with the men tending to leave together in groups. On September 23, eight of the company deserted, and three days later five more ran away from the regiment.2 These mass desertions from the Rebels were just the beginning of what became an epidemic of men absconding from the company, most never to return.

For the men who remained with the 38th, the memory of their failure at Iuka must have been painful, but the fortunes of war did not allow them much time to sit and brood. Events were already unfolding in such a way as to put the regiment squarely in the middle of the bloody battle for Corinth, and afford the men the opportunity to redeem the name of the unit.

After his narrow escape at Iuka, Sterling Price realized that his army alone was not powerful enough to defeat the Union forces in northeast Mississippi. To accomplish this goal, Price understood that he needed to unite his army with that of Major General Earl Van Dorn. Price contacted Van Dorn who was already moving his small command of 5,000 men into north Mississippi, and the two generals agreed to unite their troops at Ripley, Mississippi.3

Sterling Price put his army in motion on September 26, and his men completed the dusty

march to Ripley on the morning of September 28. With the junction of the two armies complete, Van Dorn, by virtue of his seniority, became overall commander of the combined force with Price his second in command. Van Dorn’s army consisted of the divisions of Major General Mansfield Lovell, Dabney Maury, and Louis Hebert, who had taken over Henry Little’s command after his death at Iuka. In all, Van Dorn had a force of approximately 22,000 to use against the Union army.4

It didn’t take Van Dorn long to come up with a very ambitious plan for his army. Believing an attack on Vicksburg was imminent, he felt his best option to prevent such an attack was to push the Yankees out of their staging area in West Tennessee. For this strategy to work, the Rebels first had to take the town of Corinth, Mississippi from the Federals. To advance into Tennessee with a powerful Union force intact at Corinth would have invited an attack on the rear of Van Dorn’s army.5

Although the Rebel army at Ripley was only about 26 miles southwest of Corinth, the route worked they had to travel was nearly twice that distance. Starting at Ripley Mississippi, Van Dorn’s hard marching graybacks would march north some 30 miles to Pocahontas Tennessee, just over the state line. From there they would wheel due east and advance approximately 8 miles to Chewalla Tennessee; once there the army would follow the tracks of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad southeast nearly 10 miles until they reached Corinth. The purpose of this convoluted line of march by Van Dorn was to put his men in a position to assault the federal defenses northeast of Corinth.

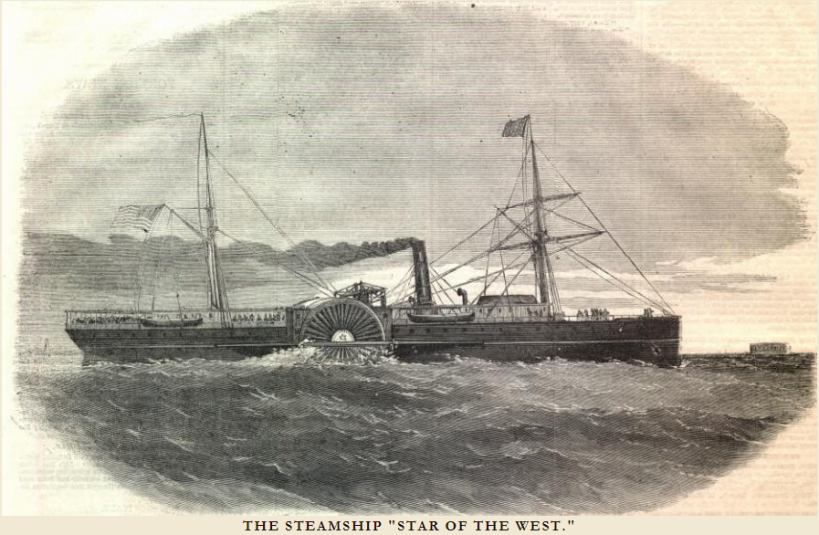

![]()

Map Showing Van Dorn’s Route of March – Ripley to Pocahontas to Chewalla to Corinth.

(Illustration from Battles and Leaders, Volume 2, page 727)

He chose to attack from this direction knowing that the outer line of earthworks defending the city were weakest in this sector.6

While Van Dorn was coming up with plans to assault Corinth, his counterpart Rosecrans was working just as hard on how he would defend the city. The Union general had 23,000 men in and around Corinth, and he kept them busy with improvements to the existing Confederate-built fortifications. To make the defenses even stronger, he ordered his soldiers to build an inner line of earthwork forts along the northern and western approaches to Corinth.7

When completed there were seven forts stretched in an arc around the city, connected to each other by a line of trenches. The names of these strongholds were batteries Robinett, Williams, Phillips, Tanrath, Lothrop, Powell, and Madison.8 Fully manned with ranks of blue infantry and gleaming brass cannon, this inner line of defense would exact a heavy toll from an attacker, a fact the 38th Mississippi was about to learn the hard way.

For the 38th, the battle at Corinth was a defining moment in the history of the regiment. The men were already laboring under the stigma of their failure at Iuka, and a second collapse on the battlefield might have permanently destroyed the soldiers’ confidence in themselves and their regiment.

The Corinth campaign began on September 30, 1862, when Van Dorn’s Rebels began the long march north to Pocahontas, arriving in the town on October 1. The gray column turned east and headed for Chewalla, entering it on the evening of October 2. At 4 a.m. on the morning of October 3, the weary men of the 38th were roused from their bedrolls, and the final leg of the journey from Chewalla to Corinth began. Van Dorn set a very fast pace, pushing his men to reach the town before federal reinforcements could arrive.9 The march was made worse for the Rebels because of the high temperature and the lack of water. James Newton Carlisle, Sr., of the 37th Mississippi Infantry wrote how the scarcity of water made the advance miserable: “Through the driest section of the Cotton States we endured the worst of distresses, thirst. What is comparable to this burning parching fever? Lack of bread is sweet in comparison.”10

As heat exhaustion and thirst took their toll on the 38th, the roadside was soon littered with dropouts from the regiment who were unable to keep up the fast pace that Van Dorn was setting. Not all the men in the regiment who dropped out did so for physical reasons, as Lieutenant Colonel Brent complained in a letter to his wife Frances:

The morning that I left camp to go into the fight, I made a report of the affective strength of my regiment it was three hundred and fourteen all told, but when I arrived at the battle field I found that the number of the regiment was only one hundred and fifty strong. This was owing a great deal to the fatiguing march that we had to make the morning of the battle, and a great deal to the cowardice of some of the men, that never had any fight in them or ever will. I have heard from the most of them and they were on their way home, no doubt they will tell great tale of what they have seen and what they have gone through with; poor cowardly devils they have not done anything but couch themselves up in some hospital or tent and fraim themselves sick. Studying up all the while to devise some plan to get home, but finding it impossible to get a proper furlough, they openly desert both from hospital and regiment, claiming to be badly mistreated, I hope the citizens will treat them with perfect contempt and as far as possible annoy them so that they will have to return to their command.11

The 38th Mississippi was going into the fight at Corinth severely reduced in numbers, but at least those that remained were tough and committed to the cause. If Lieutenant Colonel Brent led them well in the upcoming battle, they would strike a hard blow at the Yankees.

Brent kept his small command moving towards Corinth, and around 9 a.m. on October 3, the regiment halted at a point approximately 1½ miles from the outer line of federal works. Van Dorn then began to deploy his army for the assault, ordering General Lovell to form a line of battle to the right of the Memphis & Charleston Railroad, and General Price to form his two divisions between the Memphis & Charleston and Mobile & Ohio Railroads. In positioning his men, Price ordered Maury’s Division to the right, and Hebert’s Division to the left. Hebert arranged his brigade for the attack with Green’s Brigade on the left, Martin’s Brigade in the center, and Gates Brigade on the right, leaving his old brigade, now commanded by Colonel W. Bruce Colbert in reserve.12

To oppose the initial Confederate assault, Rosecrans massed along the outer works four infantry divisions, approximately 15,000 men. The Union soldiers had to spread themselves very thin to cover the outer fortifications, and they were outnumbered by the concentrated Rebel army, but Rosecrans did not intend for his men to hold out for long. He simply wanted his men to force Van Dorn to fully deploy and reveal his plan of attack.13

![]()

Initial Confederate deployment for the assault on the outer works at Corinth are shown in the upper left of the map. The Confederate troop dispositions for the second day of the battle are shown at bottom center of the map.

(Illustration from Battles and Leaders, Volume 2, page 744)

By 10:00 a.m., all of the federal skirmishers had been forced back into their earthworks, and the Rebels could begin their attack. At 11:00 Price gave the order to advance, and the 38th Mississippi marched forward with their brigade. They moved towards a gap in the Union line between the 81st Ohio Infantry and 12th Illinois Infantry that was protected by a two gun detachment of the 1st Missouri artillery (U.S.,) and the Union cannoneers made the Rebel charge a costly one as they fired round after round into the Mississippians.14 Major George H. Stone of the 1st Missouri later wrote with pride how his artillerymen met the furious Rebel assault:

Lieutenant Conant’s section, stationed near our center, was literally mowing the rebels down; but with a determination worthy of a better cause the enemy still pressed on and near the intrenchments. The infantry supporting Lieutenant Conant’s section (Eighty-first Ohio and Twelfth Illinois) were driven back, the artillery horses nearly all shot, and the cannoneers compelled to retire, leaving their guns. The defense of this section could not have been better, Captain Welker being there in person and the last one to leave his guns when all hope of saving them was gone.15

Writing to his wife Frances after the battle, Lt. Col. Brent claimed that the honor of capturing the guns of the 1st Missouri, giving her a detailed account of the action:

I stated that I succeeded in getting some hundred and fifty men drawn up in line on Friday, occupying the right of the brigade, a post of great honor. While I was getting my regt. in line of battle and posting the guides, the enemy fired a shell at me which passed within two or three feet of my head and struck a tree about ten feet from the regiment but did no damage. I then ordered the men to face down upon the ground which they did with great promptitude, in this position we remained for some thirty minutes receiving the heaviest cannonade that the mind could imagine; the enemy having gotten the exact position of my regiment began to throw their shells immediately in our ranks a killing some and wounding a great many we were therefore unable to remain in this position any longer so we were ordered to charge to protect ourselves from such a deadly fire – we did so and in a short time we had the enemy driven from their works and their guns in our hands, we did this in a short time, but nevertheless, we lossed a great many men in this charge fore we did not fire a gun until we were within forty paces of their works the reason of this was that they had fallen a great amount of timber in front of their works and we were buisily a climbing over tree tops, but when we cleared the tree tops we made the Yankees pay for it. My regiment in this charge captured two fine pieces of artillery, a Parriott [Parrott] and a rifle brass piece, we also taken several prisoners in this charge; after taking the breastwork and driving the enemy from it our men were so scattered that we were compelled to reform our lines again, which we did in a short time, and then pressed on after the enemy a driving them within Corinth – this ended the first days fight.16

The initial attack very well for the Confederates – the outer defenses had been overrun, and the Yankees forced back to their inner fortifications. It was at this point that the Rebel attack stalled due to a lack of ammunition and sheer exhaustion, and as darkness crept over the bloody field the booming of artillery and crack of musketry slowly faded away.

The 38th Mississippi had done well the first day at Corinth, but their success came at a high price. One of the first to fall was the regiments brigade commander, Colonel Martin. While leading the charge on the outer works he was hit by a shell fragment and mortally wounded. In his report on the battle General Price eulogized Martin saying, “The gallant bearing of this officer upon more than one bloody field had won for him a place in the heart of every Mississippian.”17 In the 38th Major Walter L. Kern was also wounded in the charge, hit in the right hand by a bullet while waving his sword over his head urging his men forward.18

After dark, Martin’s Brigade, now led by Colonel Robert McLain of the 37th Mississippi Infantry, was moved to a position along the Mobile & Ohio Railroad, very close to the Union lines. The exhausted soldiers dropped their bedrolls behind the embankment and tried to get some rest, but their sleep was disturbed by the sound of picks and shovels biting into the earth as the Yankees worked through the night to strengthen their earthworks before the next attack.19

Earl Van Dorn still believed he could win a decisive victory, and he drew up plans to continue the attack on October 4. The strategy he devised would put the 38th in the thick of the battle on the second day for it called on Hebert’s Division to lead off the advance to the inner Union works and thus bear the brunt of the early fighting. Hebert was ordered to advance with his division at first light against the Yankee right, and once engaged Maury’s Division would strike the center of the enemy line and Lovell’s Division the left.20

Unfortunately for the Rebel soldiers who had to carry it out, Van Dorn’s plan of attack went awry from the very start. General Hebert was supposed to lead off the attack at daybreak but reported himself sick and was relieved of duty by General Price; command of the division passed to General Martin Green, and in the confusion which followed, precious time was lost.21 When Green took over he found the division on the west side of the Mobile & Ohio Railroad facing east. The general prepared to attack by placing his brigades in the following order from left to right: 2nd Brigade (Colonel Colbert), 4th Brigade (Colonel McLain), 1st Brigade (Colonel Gates), and 3rd Brigade (Colonel Moore).22

![]() Map of the Second Day of the Battle of Corinth (www.civilwartrust.org)

Map of the Second Day of the Battle of Corinth (www.civilwartrust.org)

At 10:00 a.m. Green gave the order to attack and the long gray line began a slow wheel, or turn to the south. In this maneuver the division swung just like a gate, with the 3rd Brigade the hinge and the 2nd Brigade the outer edge of the gate, with the other brigades in between. Once they had all completed the turn and were facing south towards Corinth, the Rebels marched straight for the Yankee entrenchments.23

During the wheeling movement, the 38th Mississippi was toward the outside of formation; consequently, the men had to march a longer distance and move much faster than the regiments posted on the inside of the wheel. Thus the regiments belonging to Gates’s and Moore’s Brigades struck the Union line first, overrunning Battery Powell and threatening to cut the Union army in two. Colbert’s and McLain’s Brigades were slowed by the rough terrain they had to pass through, but at 10:30 they finally broke into an open field 400 yards east of Battery Powell. As soon as they were in the open, the Rebels were hit and their advance stopped in its tracks by the massed fire of Brigadier General Napoleon Buford’s Brigade. For nearly 45 minutes the men of the 38th Mississippi loaded and fired their muskets as fast as they could, trading volley after volley with the Yankees to their front. They kept up a withering fire until their brigade commander, Col. McLain, had his leg taken off by a well-aimed shot from a federal cannon. At this point the brigade, under a heavy fire and low on ammunition, began a quick retreat along with Colbert’s Brigade. Gates and Moore’s Brigades fared not better; after taking Battery Powell, they were subjected to a terrible crossfire and unable to advance, they had to retreat and give up the fort.24

Elsewhere on the field, Van Dorn was having the same kind of luck with his other two divisions. Maury’s was boldly repulsed with heavy losses in the attack on Battery Robinett, and General Lovell failed to attack at all.25

Having failed to take Corinth by storm, Van Dorn realized he had no choice but to order a retreat and try to get his army safely away from the city. To escape, the Rebels had to retrace the route they had taken to Corinth. The weary soldiers plodded into Chewalla Tennessee after dark on October 4 and made camp for the night. The next morning the gray column marched west and barely avoided a disaster when they found federal troops blocking their escape route over the Hatchie River Bridge. Luckily Van Dorn found another crossing of the river and the Rebels continued their march to Ripley Mississippi where the campaign ingloriously ended.26

With time to rest and reflect on the campaign, it did not take the soldiers of the 38th long to place the blame for the failure of the Corinth campaign. Lt. Col. Brent probably mirrored the feelings of many of his men when he told his wife in a letter, “I will sum up by saying that we had to fight three days in succession to get out of the trap old Van Dorn got us in.”27

For Brent the end of the campaign meant he had one very unpleasant duty to perform: making out a list of the regiment’s casualties and informing the next of kin. He started the sad news on its way in a letter to his wife:

Tell Mrs. Walker that Cicero Walker is either killed or taken prisoner I cannot say which; he was last seen on Saturday the second day of the fight on top of the enemies breast works in company with Lieut. J. W. Ball, both of whom have not been heard of since, you can tell her that we have sent some of our men back to bury the dead and that they will be hear in a few days, and I can then probably give her some information about him…my old company under the command of J. C. Williams went into the engagement with eighteen or twenty men we had four killed and some four or five wounded. I will have in a short time a list of the killed and wounded of my regiment made out and published for the benefit of the citizens.28

Considering the small number of men the 38th Mississippi took into the fight at Corinth, an examination of their casualty list shows they had fairly high losses. Of 150 men engaged in the battle, nine were killed, twenty-five wounded, two were missing, and thirty-five taken prisoner.29

The battle of Corinth had been a bloody defeat for the Confederacy, but for the rank and file of the 38th Mississippi, it was a moral victory, for the regiment had proved it could fight hard when properly led. This had a pronounced psychological effect on the men, for they knew they had redeemed themselves for their failure at Iuka. A newspaper article saved by the family of Preston Brent expressed the importance that the regiment attached to the battle of Corinth:

It will be remembered that the 38th Miss. Regiment achieved an unenviable notoriety in Iuka. Being a new regiment, and the engagement at Iuka being the first it was placed in, it did not stand the severe crossfire…but in the battle of Corinth it blotted out every stain that may have been attached to it by the Iuka affair, and fought gallantly hand to hand with the oldest veterans in the service. The regiment now stands forth marked for its struggle in the Corinth fight and came out the proudest of the proud.30

The 38th Mississippi went into the battle of Corinth a small regiment, and came out an even smaller regiment, but the survivors were now veterans, toughened by the rigors of war. During the winter of 1862-1863 as the regiment recruited and built up its strength, these men would teach the new recruits the lessons they had learned at such high cost.

1 Preston Brent to Frances Brent, 12 October 1862. Original letter owned by Paul Crawford (Brookhaven, MS).

2 Muster roll, CSR-MS, Record Group 9, rolls 62-65.

3 Cozzens, 135.

4 Official Records, Series 1, Volume 17, Part 1, 376-384.

5 Ibid., 452-453.

6 Cozzens, 137.

7 Moneyhon and Roberts, 159.

8 Official Records, Series 1, Volume 17, Part 1, 171.

9 Official Records, Series 1, Volume 17, Part 1, 385; Cozzens, 155.

10 Corinth, Mississippi. Daily Corinthian, 8 October 1962.

11 Preston Brent to Frances Brent, 12 October 1862. Original is owned by Paul Crawford of Brookhaven, MS.

12 Cozzens, 166-167; Official Records, Series 1, Volume 17, Part 1, 385.

13 William S. Rosecrans, “The Battle of Corinth,” in Battles and Leaders, ed. Clarence Buel and Robert Johnson, (Edison, NJ: Castle Books, Reprint, n.d.), 2: 744-745.

14 Cozzens, 178-179.

15 Official Records, Series 1, Volume 17, Part 1, 268.

16 Preston Brent to Frances Brent, 12 October 1862. The original letter is owned by Paul Crawford of Brookhaven, MS.

17 Official Records, Series 1, Volume 17, Part 1, 386.

18 Lexington (Mississippi) Advertiser, 6 December 1901.

19 Clarke, 49.

20 Cozzens, 229.

21 Official Records, Series 1, Volume 17, Part 1, 387.

22 Ibid., 389-390.

23 Ibid.

24 Cozzens, 240-251.

25 Moneyhon and Roberts, 143.

26 Ibid.

27 Preston Brent to Frances Brent, 12 October 1862. The original letter is owned by Paul Crawford of Brookhaven, MS.

28 Lieutenant Jesse W. Ball and Private Silas Cicero Walker were taken prisoner during the attack on October 4. Both were later exchanged and returned to duty with the regiment. Muster roll, CSR-MS, Record Group 9, rolls 62-65; Preston Brent to Frances Brent, 12 October 1862. The original letter belongs to Paul Crawford of Brookhaven, MS.

29 Muster roll, CSR-MS, Record Group 9, rolls 62-65.

30 Undated newspaper clipping from the collection of Paul Crawford of Brookhaven, MS.

[End of Chapter 4]

Chapter V

The Winter of 1862-1863

I don’t expect to get to camp before tomorrow the mud is frozen shoe mouth to half leg deep so you know that we have hard times on this march.1

– Private James Floyd of the Wilkinson Guards, December 5, 1862.

In late October the 38th Mississippi with the rest of the army was ordered to Camp Rogers, located several miles outside Holly Springs, Mississippi. Here the exhausted and foot-sore Rebels finally had an opportunity to rest and recover from nearly two months of active campaigning. The location of the camp was well chosen; Sergeant Willie Tunnard of the 3rd Louisiana Infantry said the camp “…was a pleasant one, on the hills, amid the shadows of large oak-trees. In front of it were wide extended fields, formerly cultivated in cotton, now covered with corn stubble.”2

Once they reached Camp Rogers, the high command immediately set to work rebuilding

the army and making good the losses due to casualties and desertion. Toward this end, Robert McCay, acting major of the 38th since the wounding of Walter Keirn at Corinth, received the following orders on October 24:

Maj. R. C. McCay of the 38th Miss. Regt. is hereby detailed to proceed to the camps of instruction at Brookhaven and Enterprise Miss. to receive such conscripts as may be assigned to the 38th Miss. Regt. by the proper state authority and conduct them at once to this command. He will also assemble and conduct to this command all officers and men now absent without proper authority.3

Gathering conscripts and running down deserters to fill the ranks of the regiment continued all winter long, but in the end the effort only met with marginal success. In a roll of the unit taken in February 1863, the 38th was able to muster only 264 men.4

While the 38th was being rebuilt, the army itself was undergoing a massive reorganization, starting at the top with General Van Dorn. In the wake of his disastrous Corinth campaign the Mississippian was transferred to a cavalry command and replaced by Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton. He was assigned command of the Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana on October 1, 1862, and he arrived in Jackson on October 14 and began to sort out his new army.5

In the shakeup of the army that followed the change of command, General Hebert was

relieved as head of a division and sent back to lead his old brigade; the division was given to Major General Dabney H. Maury. For the 38th, the death of Colonel Martin led to the breakup of the brigade and the Mississippi regiments were assigned to General Hebert. After the transfer, Hebert’s Brigade consisted of the following units:

3rd Louisiana Infantry

21st Louisiana Infantry

7th Mississippi Infantry Battalion

36th Mississippi Infantry

38th Mississippi Infantry

43rd Mississippi Infantry6

Assigning Mississippians and Louisianans to the same brigade was not an instant success as there was considerable friction between the two groups. The 3rd Louisiana and 21st Louisiana were early war regiments comprised of volunteers who enlisted at the very beginning of the conflict. They were proud men and they considered serving beside Mississippi troops, many of whom were conscripts, to be an insult. Sgt. Tunnard of the 3rd Louisiana recounted the following incident that illustrates the feelings in his regiment:

General Hebert came into camp, and was immediately surrounded by the men, who complained bitterly that they were put in a conscript brigade. The general replied: ‘Never mind, my men; never mind. You will soon make good soldiers of them all.’ The compliment thus delicately paid to the efficiency of the regiment did not soothe the irritated and discontented feelings.7

While the animosity of the Louisianans faded over time, it never completely disappeared, and relations with the Mississippians were strained the entire time the two groups served together.

As John C. Pemberton went about the task of reorganizing his department, Ulysses S. Grant was preparing his troops for a drive on Vicksburg. On November 2, 1862 he moved five divisions to Grand Junction, Tennessee, and on November 8 the vanguard of a 31,000 man Yankee force swarmed into Mississippi, marching for the town of Holly Springs.

![]()

38th Mississippi Area of Operations, Winter 1862

(www.angelfire.com/ms2/grantshilohvicksburg/)

Pemberton responded to the invasion of Mississippi by ordering his troops south to the strong defenses behind the Tallahatchie River at Abbeville. Union cavalry entered Holly Springs on November 13, and by December 1 Federal troops were crossing the Tallahatchie River.8

The steady advance of the Yankees forced Pemberton to order another withdrawal, this time behind the Yalobusha River at Grenada. Terrible weather conditions made the march a miserable one for the men of the 38th, as they had to journey through a nasty winter storm with a hostile army nipping at their heels. Private James Floyd of the Wilkinson Guards described the hardships in a letter to his wife Mary:

…we left camp alone near Abberville on Monday the 1st day of this month after lying in the breastworks for two days and nights and have been marching every night still it is raining, all night and this morning is sleeting and snowing…we have plenty hard times with poor soldiers [in] such weather as this. I don’t expect to get to camp before some time tonight or tomorrow the mud is frozen shoe mouth to half leg deep all the way so you know that we have hard times on this march.9

The constant exposure to the elements caused a serious downturn in the health of the regiment, and in November and December sixteen men in the 38th died of disease; nine more were so weak that they fell out of the march and were captured by the enemy.10

With the Confederate army safely behind the Yalobusha, Grant decided on a bold gamble to try and take Vicksburg. While his troops pinned the Confederates at Grenada, General Sherman took 30,000 men from Memphis and transported them down the Mississippi River by steamboat to strike directly at Vicksburg. Grant’s plan with awry almost immediately when Confederate raiders under Earl Van Dorn captured and destroyed Grant’s supply base at Holly Springs, Mississippi. With his army deep in enemy territory with no supplies, Grant was forced to withdraw to Memphis, ending his first attempt to take Vicksburg. Sherman fared no better with his end run on the Hill City; his attack at Chickasaw Bayou ended in a bloody defeat on December 29, 1862. In the wake of this setback, Sherman loaded his men back on their transports and slowly steamed north, ending the 1862 campaign against Vicksburg.11

The immediate threat to Vicksburg was gone, and Maury’s Division was transferred to Snyder’s Mill, twelve miles north of the city on the Yazoo River, arriving on New Year’s Day 1863.12

The 38th Mississippi manned a set of fortifications on a bluff overlooking the river with the assignment of protecting a series of log rafts that were anchored at the mouth of the Yazoo to keep Union gunboats from entering the waterway.13

The regiment spent many quiet months at Snyder’s Mill, and the only action the rank and file saw was their own officers fighting among themselves. The problem developed in late December when Lt. Col. Brent applied for promotion to Colonel to fill the vacancy left by the resignation of Fleming W. Adams in September. Brent’s moving into the Colonel’s slot started a chain of promotions, with Major Keirn advancing to Lieutenant Colonel,14 Senior Captain McCay to Major, and Daniel Seal to Senior Captain. This series of promotions should have been a routine clerical matter, but Captain Seal threw a gigantic monkey wrench into the proceedings when he protested that the Lieutenant Colonel’s commission was rightfully his. Captain McCay angrily spelled out Seal’s self-serving plan in a seven page statement:

I now approach the immediate cause of this contestation, if from it’s novel character in many incidents it can be dignified with the appellation. On the 24th Septr. Col. F. W. Adams resigned his position, thereby casting the character of heirs apparent upon Lt. Col. Brent, Major W. L. Keirn, and myself as first Senior Captain, of the respective positions of Colonel, Lt. Colonel, and Major. To the promotion of Col. Brent it is understood no objections have been urged, but Captain Seal, Second Senior Captain, has recently discovered, that his pretensions are superior to those of Maj. Keirn Lt. Col. and Captain McCay for that of Major and has actually obtained a commission as late as the 3rd day of January 1863 showing that his original commission of 25 March 1862 was erroneous and that his election having taken place on the 8th day of March 1862, his commission should have issued at that time, and consequently that the claims of Maj. Keirn dating 15th March 1862 and of Capt. McCay dating 19th March 1862, must yield as junior commissions.15

Captain Seal’s little scheme to gain the Lieutenant Colonelcy of the regiment aroused the ire of Preston Brent, who quickly fired off a letter in support of Keirn and McCay, stating for the record:

That from the roster of the regiment, it does not appear that Captain Seal ranks either of the two named Captains and nothing has come to my knowledge until very recently to induce me t believe that Captain Seal had other pretensions than those recognized in his position as Second Senior Captain.16

Brent went on to point out that even if Seal’s claim was correct and he did rank Keirn and McCay by date of commission, he had forfeited any right to the promotion by not speaking up when he was first assigned as Second Senior Captain. In a show of solidarity for Keirn and McCay, the regimental adjutant and eight of the regiments company commanders signed Brent’s letter, acknowledging that they agreed with his decision in the matter. Even though the officers of the 38th were firmly against Seal, his claim had to be investigated by the high command, and thus the promotion process slowed to a crawl. Eventually General Hebert was forced to intervene personally in April 1863 when he sent a letter to the Confederate Adjutant and Inspector General’s Office requesting that the promotions for Brent, Keirn, and McCay be validated. The generals letter did the trick, and all three received their promotions, back dated to September 24, 1862, the day Col. Adams resigned.17

Rather than mire himself in a no-win fight for a promotion, Captain Seal should have concerned himself more with commanding his company. The Hancock Rebels had the highest rate of desertion and absenteeism in the entire regiment, and the problem was only getting worse, not better.18 The situation was so severe that transfer out of the company was preferable to some rather than continue under Seal’s leadership. Private Joseph Pendleton said in a letter to his sister “I am getting awful tired of this company. I wish I could get a transfer into another company.”19 The young soldier was as good as his word – he transferred to the Holmes County Volunteers shortly thereafter and served his new company faithfully until the end of the war.20

Other than the promotion squabble, the only real complaints in the regiment were about the quality of the food issued and the boredom of camp life at Snyder’s Mill. Joseph Pendleton wrote to his sister in March 1863:

Oh how I wish I had some butter and eggs and cakes. The officers get plenty of favors and we privates don’t get any at all…Sister you don’t know how much help to my mind if I had some interesting books to read. I am so lonesome here. My little testament is a good friend to me. I would write oftener if I had the paper, it cannot be gotten easily.21

Private Pendleton was not alone in seeking comfort from his bible; in the spring of 1863 Confederate soldiers throughout the south were swept up in a wave of religious revivalism, and many in the 38th Mississippi were eager participants. Pinkney Johnston, the regimental chaplain of the 38th wrote of the religious tumult sweeping through the rank and file saying,

We have had for the past week very interesting prayer meetings. They were well attended

and the very highest interest manifested. Souls are hungry for the ‘bread of life’. Often in these prayer meetings there are from twelve to twenty mourners [someone who has not been saved]. There have already been two or three conversions, and four have joined the church. Sinners are being awakened, mourners comforted, and the Christian established in the faith.22

When not on duty or attending religious services, the men did their best to break up the monotony of camp life, as Erastus Hoskins illustrated in a letter to his wife, explaining to her how the soldiers entertained each other:

Our ‘boys’ amuse themselves in various ways – some tusling some having game chickens fighting &c it is astonishing some times to see them – after lying in the trenches all night – they are as lively as if they had just started out.23

The boredom of camp life was briefly interrupted on March 14 when General Grant sent a small naval force up Steele’s Bayou north of Vicksburg with orders to find a useable route to get behind the Vicksburg defenses. The fleet of five ironclads plus their auxiliary vessels were supported by a division of infantry from General Sherman’s XV Corps.24 In response to this incursion, Pemberton organized a detachment at Vicksburg commanded by Brigadier General Stephen D. Lee to follow the Yankees and harass them from the rear.25

For Lee’s expedition to be successful, men were needed who were familiar with the

swampy wilderness of Steele’s Bayou, and a detachment from the Holmes County Volunteers led by Lieutenant Samuel Gwin was selected to go on this mission.26 In a letter to his wife Erastus Hoskins mentioned the uproar that the Yankee expedition had caused in camp:

I saw a flat boat come down the river loaded with negroes which the owner had [brought] from Deer Creek. He reported 7 gunboats in Deer Creek and about 10,000 infantry and cavalry troops there. I can’t believe there is so many. As most persons not in the army see a few thousand men together magnify the number. Genl. Hebert is busy in having guns planted so as to range up the river in case the gunboats should attempt to come down here. We have not heard from Sam and Edgar Gwin since they left – I believe I mentioned that they called for 30 men from this regiment and one Lieut. to go up the river picketing – they were all taken from John’s Company [John Hoskins, Capt. of Co. A] and Lt. Gwin in command of the 30. The call was for 250 from the brigade – I don’t know what point they were sent.27

Lee’s Rebels made life very hard for the Yankee expedition, felling trees to impede the progress of the boats and constantly sniping at the enemy. The federals were forced to withdraw to avoid the capture of the little fleet, and by March 27 the ships had reentered the Mississippi River.27

Lieutenant Gwin’s detachment from the Holmes County Volunteers did not return after the Yankee threat ended; instead they remained stationed north of Vicksburg, and it turned out that they did not see the rest of the regiment for nearly six months. This stalwart little band went far and saw much in that time, and their adventures will be dealt with later in the narrative.

One other interesting event that took that spring was the replacement of the 38th’s division commander. General Maury was transferred, and Major General John H. Forney replaced him in April 1863.28

The 38th’s peaceful respite at Snyder’s Mill abruptly ended the night of April 30 1863, when the Union navy attempted to enter the Yazoo River. The fleet consisted of three gunboats and eight transports, and while they looked very fearsome, they were simply acting as a diversion so that Grant could land his army below Vicksburg. The gunboats put up a good front, attempting to know out the Rebel artillery on the bluffs, but after a two-day bombardment that caused little damage, the enemy ships withdrew and sailed back downriver. During the heavy cannonade the soldiers hugged the bottom of their entrenchments and the 38th reported no casualties.29 It was a bloodless beginning to the regiment’s bloodiest campaign: the siege of Vicksburg.

1 James Floyd to Mary Floyd, 5 December 1862. The original letter is owned by Mrs. Ada Smith of Crosby, MS.

2 Willie H. Tunnard, History of the Third Regiment Louisiana Infantry (Baton Rouge, LA: By the Author, 1866), 210.

3 Order, W. W. Witherspoon to Robert C. McCay, McCay Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

4 Rowland, Military History, 332.

5 Official Records, Series 1, Volume 17, Part 1, 3-4.

6 Stewart Sifakis, Compendium of the Confederate Armies: Louisiana (New York: Facts on File, 1995), 71-72, 108-109; Sifakis, Compendium: Mississippi, 83, 125-129, 134.

7 Tunnard, 213.

8 Official Records, Series 1, Volume 17, Part 1, 466-472.

9 James Floyd to Mary Floyd, 5 December 1862. The original letter belongs to Mrs. Ada Smith of Crosby, MS.

10 Muster roll, CSR-MS, Record Group 9, rolls 62-65.

11 Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. Volume 1: (New York: J. J. Little and Company, 1885), 428-433.

12 Official Records, Series 1, Volume 17, Part 1, 679.

13 Jones, Rank and File, 17-18.

14 At this time the seriousness of the wound Keirn received at Corinth was not known, and it was believed that he would return to the regiment. In fact, his hand was badly mangled, leaving him unfit for combat. Keirn tendered his resignation as Lt. Col. on July 13, 1864. Resignation, CSR-MS, Record Group 9, roll 64.

15 Robert C. McCay to Louis Hebert, Undated, McCay Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

16 Preston Brent to _____, 22 December 1862, McCay Papers, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

17 Muster roll, CSR-MS, Record Group 9, rolls 62-65.

18 Ibid.

19 Joseph W. Pendleton to Sarah Jennings, 1 March 1863. A copy of this letter is in the collection of the Confederate Research Center, Hillsboro, TX.

20 Muster roll, CSR-MS, Record Group 9, roll 64.

21 Joseph W. Pendleton to Sarah Jennings, 1 March 1863.

22 William W. Bennett, A Narrative of the Great Revival Which Prevailed in the Southern Armies (Harrisonburg, VA: Sprinkle Publications, 1989), 268-269.

23 Erastus Hoskins Letters, 1 March 1863.

24 Warren E. Grabau, Ninety-Eight Days (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2000), 7.

25 Jim Miles, A River Unvexed (Nashville, Rutledge Hill Press, 1994), 312.

26 Record of Events, Company A, 38th Mississippi Infantry, CSR-MS, Record Group 9, roll 62.

27 Erastus Hoskins Letters, March 1863. Note: the first page of the letter is missing so the exact date the letter was written is not known.

27 Miles, 313.

28 Sifakis, Compendium Mississippi, 129.

29Official Records, Series 1, Volume 24, Part 1, 577-578.

[End of Chapter 5]

Chapter VI

The Siege of Vicksburg

For two weeks have the enemy been hammering at the gates of Vicksburg and still she refuses to open unto them.1

– Captain William L. Faulk, May 30, 1863

While Sherman distracted Pemberton with his demonstration against Snyder’s Mill, Grant crossed the Mississippi River with an army of 44,000 at Bruinsburg on May 1, 1863. Once on Mississippi soil, Grant moved quickly and decisively, never allowing the Confederates to unite their superior forces against him. In the space of seventeen days the federals fought five major battles, winning them all: Port Gibson on May 1, Raymond on May 12, Jackson on May 14, Champion Hill on May 16, and Big Black River on May 17. The 38th took no part in these battles as Forney’s Division was ordered to remain at Snyder’s Mill to protect Vicksburg.2

After the Confederate defeat at Champion Hill on May 16, orders went out the next day from Pemberton for Forney’s Division to march for Vicksburg and move into the entrenchments. General Hebert received the order at 11:00 a.m. and quickly issued orders for supplies to be gathered and sent to Vicksburg, and to burn anything that could not be moved. At 7:30 p.m. he formed his brigade and the march to the hill city began. The Rebel column journeyed through the night and the weary men of the 38th arrived in Vicksburg at 2:30 a.m. on May 18th.3

Hebert’s Brigade was ordered to the earthworks in the rear of the city, charged with defending the line of entrenchments between the Graveyard Road and Jackson Road.

![]()

Hebert’s Brigade held the portion of the Vicksburg trenches from Stockade Fort to the Great Redoubt south of the Jackson Road. At the beginning of the siege the 38th was located several hundred yards south of the Stockade Fort.

(Illustration from Map of the Vicksburg National Military Park, Published by the Park Commission, no date.)

Hebert deployed his brigade in the following order from left to right: the 36th Mississippi held the Stockade Redan, a large earthwork fort guarding the Graveyard Road; next came the 7th Mississippi Battalion, 37th Mississippi, 38th Mississippi, and 43rd Mississippi; the 3rd Louisiana held a redan north of the Jackson Road, and the 21st Louisiana anchored the brigade right flank in the Great Redoubt on the south side of the Jackson Road.4 Because the Graveyard and Jackson Roads were natural avenues of approach to the city, the section of the line held by Hebert’s men was destined to be the scene of some of the most intense fighting of the siege.5

The vanguard of the Union army reached the outskirts of Vicksburg near sunset on May 18, 1863. Despite the fact that Pemberton had nearly 30,000 well entrenched soldiers defending the city, Grant believed the Confederates were so demoralized from their recent defeats they could not withstand a direct assault.6 The general ordered the attack to begin at 2:00 p.m. on May 19, and at the appointed hour the Yankees stepped off towards the Rebel works. The Stockade Redan was a focal point of the Union attack and was the scene of a series of ill-coordinated assaults by the 15th and part of the 17th Corps.7

As the blue wave advanced towards the 38th’s position, the regiment’s skirmish line out in front of the main line of works commanded by Lieutenant Hansford Lanehart began a quick retreat to the safety of the trenches. During the dash to cover, Lanehart was struck by an enemy ball and mortally wounded, becoming the 38th’s first casualty at Vicksburg.8

The Yankee troops closing on the regiment’s position were the 95th Illinois and 17th Wisconsin of Brigadier General Thomas Ransom’s Brigade, and their advance was stopped in it’s tracks by the destructive hail of lead poured into the blue ranks by the 37th and 38th Mississippi.9 Colonel Thomas W. Humphrey of the 95th Illinois wrote in his after action report why their assault failed:

…ordering my command forward, we charged across the first ravine, over an almost

impassable abatis of felled timber, exposed to direct and concentrated fire of musketry and a murderous enfilading fire from the enemy’s batteries of the redan on our right front, and the heavy works on the Jackson road (erroneously called Fort Hill) on our left. Being unsupported, I deemed it rashness to proceed farther, but held my position with colors planted within 100 yards of the enemy’s lines.10

The Union attack fared no better along the other sections of the front, and the federals were unable to break through the Confederate defenses. Losses in the 38th Mississippi from the attack were very light, only one killed and three wounded.11 Captain William L. Faulk recorded in his diary on May 19 “We have fought the enemy very hard today and held our positions well along the line…I thank almighty God for his protection through the past days.”12

Grant was undaunted by the losses his army suffered on the 19th, and he prepared his men for an even larger and better-coordinated assault set for May 22. To help soften up the Stockade Redan before the attack, the federals employed 27 cannon on either side of the Jackson Road to blast the Rebels and wear down their defenses. Because of the storm of iron being thrown at them, the 38th was constantly working to repair the damage done to the parapets by the Union cannoneers. At 10:00 a.m. on the 22nd Grant gave the order to attack and a wave of blue soldiers stepped off towards the Confederate works. At the Stockade Redan, the Union soldiers in the van of the attack were 150 volunteers carrying planks and scaling ladders. Known as the “forlorn hope,” their mission was to bridge the ditch in front of the fort and then scale the parapet. The rebels poured a terrible fire into the Yankees, inflicting very heavy casualties. A few of the survivors reached the ditch in front of the redan and were pinned there until nightfall allowed them to scamper to safety.13

During the initial attack the 38th’s position was not directly assaulted, allowing the Mississippians to deliver a deadly flanking fire into the 23rd Indiana Infantry which was advancing to the regiment’s right against the 3rd Louisiana Redan. The heavy volleys from the 38th slammed into the Hoosiers and forced them to break off their attack and drop to the ground to seek shelter from the fire that was decimating their ranks.14

At 2:15 a second Union assault wave was ordered into the fight at the Stockade Redan. In

the 38th’s front Ransom’s Brigade advanced in four columns, only to be met by a withering fire from the Mississippians. General Ransom later wrote of the attack,

The enemy had in the mean time massed troops behind their works in our front, and poured into my ranks one continuous blaze of musketry, while the artillery on my left threw enfilading shot and shell into my columns with deadly effect.15

The bravery of the federals in the face of such overwhelming fire made quite an impression on the Rebels, and years later Captain James H. Jones was moved to write about the gallantry he witnessed that day at Vicksburg:

When the cannonade ceased the Federals formed three [four] lines of battle, near the woods, and began a steady advance upon our works. Their lines were about one hundred yards apart. They came on as rapidly as the fallen timber would permit, and in perfect order. We waited in silence until the first line had advanced within easy rifle range, when a murderous fire was opened from the breastworks. We had a few pieces of artillery which ploughed their ranks with destructive effect. Still they never faltered, but came bravely on. It was indeed a gallant sight though an awful one. As they came down the hill one could see them plunging headlong to the front, and as they rushed up the slope to our works they invariably fell backwards, as the death shot greeted them. And yet the survivors never wavered. Some of them fell within a few yards of our works. If any of the first line escaped, I did not see them. They came into the very jaws of death and died…Surely no more desperate courage than this could be displayed by mortal men.16

After a mauling that lasted forty-five long minutes, the survivors of Ransom’s Brigade were withdrawn, ending the action on the 38th’s front. A short time later Colonel Brent was ordered to move the regiment by the left flank to reinforce the 36th Mississippi at the Stockade Redan. This movement under fire was not an easy one as Captain Jones related:

I will remember having to pass along a space of perhaps 20 feet where the trenches were not completed and therefore exposed the men to the enemy’s fire. Some few of the company ahead lay on their stomachs and refused to move thus impeding the movement. I made a rear attack with the point of my sword on their most exposed parts and set them in motion again.17

Grant acknowledged that Vicksburg could not be taken by direct assault after the failure of his army to break the Confederate line on May 22, and he decided to besiege the city and starve the Rebel garrison into submission. For the 38th, the war was now a waiting game in the trenches with the threat of death a constant companion. Captain Jones wrote of the long days spent in the trenches:

…it was by no means a dull routine. The thunder of the cannon greeted us by day and by night; the sharp crack of the rifle, the hiss of the minie ball; somebody wounded; somebody dying – all the time.18

Besides having to worry about their own personal safety, the men in the 38th also had to worry about their families, many of whom were living in Union occupied territory. Captain Faulk spoke for the fears of many when he wrote in his diary on May 26:

All worried and tired, but still determined to endure all for what we believe to be our rights, and confident that an over-ruling providence will work all for our good. The enemy may be a superior force, overcome us for a short time, but God will never favor the persecutors of innocent women and children. They have passed by my home and I cried to hear the condition in which I fear they have left my wife and children. God will certainly visit them with a terrible vengeance.19

For most of the 38th, time passed very slowly as they sat in the trenches under a boiling sun, warding against a Yankee attack. Company H however had a more interesting time as they spent their days during the siege acting as the brigade provost marshal. The record of events for the company stated the men were “…in discharge of the dangerous duty of patrolling the small area of the siege, arresting stragglers and conducting them under guard to the different commands in the trenches.”20

Life got more interesting for the regiment on June 2, when the 38th was ordered to take a new section of the entrenchments, just to the right of the 3rd Louisiana Redan on the Jackson Road.21 As the men filed into their new position under cover of darkness, Eleazer Thornhill heard someone mutter, “Boys you will smell hell there,”22 and the prediction proved to be entirely correct. The line of entrenchments the 38th was now responsible for defending was very exposed, and casualties from Union sharpshooters happened with terrible regularity. The Yankees had even erected a tower in their lines to look down into the Confederate trenches and shoot at the exposed Rebels. When the men did return fire, they did so at a distinct disadvantage, as James H. Jones related in his memoirs:

Even in the matter of sharpshooting we were at a great disadvantage, because our works were located above those of our foes. One would think this gave us an advantage, but it was not so. The firing was done through port holes, and ours, being depicted against the sky, revealed the sharpshooters instantly, and exposed them to the fire of their opponents. Those of the Federals on the other hand were invisible and could not be easily located. To use these ports meant instant death, and the men preferred to stand up boldly and fire over the breastworks at the enemy, and risk the chances of a return fire.23

Under cover of the deadly fire by their sharpshooters, Union soldiers dug approach trenches up to the 38th’s earthworks. Sergeant Clarke of the 36th Mississippi said the federals were so close to the 38th’s position, “…dirt from the two ditches blended together.”24

To combat the enemy at such close quarters, the men began to use six and twelve-pound shells as improvised hand grenades, throwing them into the Yankees ditches. Captain Jones described this type of warfare as having “…the appearance of a ball game, only the players never caught the balls, but fled from them.”25

The Yankees pulled something new from their bag of tricks on June 25 when they exploded a mine under the 3rd Louisiana Redan, followed by a wave of blue troops who poured into the resulting breach in the Confederate line. The surprise attack quickly turned into a trap for the federals as they were met by a hail of bullets and were unable to get out of the crater they had charged into. Captain Faulk of the Van Dorn Guards witnessed the explosion and later wrote in a letter, “I was aroused by a tremendous report and jumping up to discover a short distance away to my left that dirt was flying up in the air about one hundred feet high.”26 The 38th’s position was not directly attacked during the assault, freeing the Mississippians to pour a scathing flanking fire into the Yankees. Eleazer Thornhill recalled that during the fight:

John and Wash Polk were right in the hottest of the charge on top of the breastworks, and fired down among the enemy. I looked to see them fall dead, but God shielded them, and they came down unhurt from the place where the bullets flew so thick and fast. It seemed as though it would have been impossible to have escaped unhurt. There is nothing impossible with God. He will have mercy on whom he choose.27

The Yankee attack was smashed, and the 38th, protected by its entrenchments, suffered very low casualties, only one dead and three wounded.28

One other source of heavy casualties in the regiment during the siege came from the Union artillery. The 38th was sandwiched between two major targets for the cannoneers; the 3rd Louisiana Redan on their left, and the Great Redoubt on their right, so there was a blizzard of iron being thrown their way. The Yankees tended to mass their guns during the siege to establish a massive superiority of fire over their Rebel opponents, and nowhere along the lines was this more true than at the 3rd Louisiana Redan. At one point the Federals had over 100 guns firing against the Confederate strongpoint.29 Death in the form of an explosive cloud of iron could claim a victim at any moment, and it made life in the trenches very uncertain for the soldiers. Captain Faulk recorded once such instance in his diary:

June 1. Some artillary firing last night opposite our lines. Heavy on the right about 3 o’clock. Shell bursted in Co. A last night just after dark killing three men and wounding two. Their provisions had just come in and they were sitting around eating their suppers when a shell exploded in their midst, showing how little we know at what moment the summons of death may come and the uncertainty of life.30

As the siege ground on, one of the main concerns for the rank and file in the trenches was getting enough food to eat, as the rations were continually being reduced, and hunger became an ever-present companion. Private Eleazer Thornhill still had a keen memory of how much food the soldiers had to survive on during the siege when he wrote his memoirs many years later:

I will give you a sketch of our suffering for food. It was very scarce with us, although said to have been a good deal surrendered up to General Grant. I don’t know whether it was so or not, but one thing it came scarce to us. We got a small piece of bacon once in a while. At night a small lot of peas and bread, and near one pint of boiled peas was a two day’s ration. Sometimes it would be a bit of poor beef, and towards the last they would fetch poor mules into camp for food. I always threw mine away, I could not eat it at all, and it was what I called 48 days starvation.31

Despite the hardships, the men were still determined to defend Vicksburg to the last, but they realized that when the food supply ran out, surrender would soon follow. Captain Faulk recorded in his diary on June 13, “We are nearly worn out with the ditches, but will hold out as long as provisions last.”32

After suffering through sharpshooters, artillery, and lack of food, the 38th received

another blow to it’s morale on June 30 when Colonel Brent was seriously wounded by a federal sharpshooter. He was up on the front line when he heard someone call his name, and when he instinctively looked up, his head was over the parapet and was instantly struck by a minie ball which passed through both cheeks. In his parole record it was noted that Colonel Brent cleaned the wound himself by taking a silk handkerchief and running it through both cheeks to cauterize the holes.33 Preston Brent survived his terrible wounds, but he was never able to go back to the 38th. Disfigured and in poor health, his body was broken, but the discipline and fighting spirit he instilled in the men remained to carry the regiment through two more dark and bloody years of war.34

Command of the 38th Mississippi passed to Major Robert McCay after Brent was wounded, but he was ill and confined to a hospital in Vicksburg for much of the siege. Ironically the leadership of the regiment passed to Senior Captain Daniel Seal, the man who had tried so desperately the winter before to obtain a staff officer’s commission. Exactly how much commanding Seal did during the siege is open to debate however. In a post-war letter James H. Jones wrote a less than flattering account of Seal’s leadership at Vicksburg:

Seal himself was rarely in the trenches but staid somewhere in the city all the time. I commanded the regiment after Col. Brent was wounded, but Seal claims that he was in command. There was but little commanding to do, but I did that little.35

As June gave way to July with no hope of relief in sight and the food supplies in the garrison running low, Pemberton began negotiations with Grant and surrendered Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. The 38th had an excellent view of the meeting between the two generals as they met about 30 yards in front of the regiment’s position. Once the meeting concluded the men realized that the siege of Vicksburg was over at last.36

The decision to surrender on July 4th was very unpopular with the rank and file, and Captain Faulk spoke for many when he recorded this passage in his diary:

How humiliating it is for us to be compelled to submit to such an enemy, and that too on the 4th of July; be we have done all that men could do – we held them 48 [47] days on very scant rations and we would have continued to hold the place had our rations held out.37

Under the terms of the surrender, the officers of the 38th were allowed to keep their side arms and any horses they personally owned. The most significant term however was that all of the soldiers were to be paroled rather than sent to Northern prison camps.38 With the negotiations complete, the 38th Mississippi Infantry formed ranks at 10:00 a.m. on July 4, and marched out in front of the earthworks they had defended so faithfully. Before the surrender was completed, the regiment was hit with one final tragedy to mark the end of the Vicksburg campaign. While the men were stacking arms, a detail behind them in the trenches was gathering up discarded weapons. One of the muskets accidentally discharged and the ball hit Private Samuel S. Miller of the White Rebels. Eleazer Thornhill vividly remembered the freak accident in his memoirs:

After we were surrendered by Gen. Pemberton to Gen. Grant of the Federal army, orders were issued to gather up all the loose guns that were lying in the ditches, and stack them up. We had marched eight or ten paces beyond our fortifications and were arranging our guns. Miller was touching me on my right and a man on the right of him. His name I have forgotten. The first gun that Lewis Guy threw up on the fortress was an old musket, loaded with buckshot. The hammer in striking the hard clay caused it to explode and six or seven shot entered Miller between the shoulders, making a slight wound in the flesh. Miller turned around and inquired who did it, and never again uttered a word. He began to fall, and I saw the blood beginning to flow from his mouth. We held him and soon life was extinct. I was one of the detail that helped bury him.39

It was a bad ending to a very bloody campaign for the regiment, and the men had paid a dear price for their stubborn defense of the hill city. According to a statement made by Captain Seal after the siege, thirty-five men were killed at Vicksburg, three of them officers; Captain Leander M. Graves of Company F, Lieutenant Hansford Lanehart of Company D, and Captain Walter A. Selph, the regimental commissary officer. Thirty-two enlisted men and five officers were listed among the wounded, including Colonel Brent. When the two men who were missing were added to the toll, the total casualties in the regiment stood at seventy-four men.40

Captain Seal’s estimate of the number of soldiers killed in the regiment is actually low, for it does not include those men who died from their wounds after the siege ended. An examination of the compiled service records for the 38th shows that when these men are added, the regiment’s death toll at Vicksburg was forty-three men.

Shortly after the siege ended a newspaper published a list detailing each Confederate unit that surrendered at Vicksburg and the number of men paroled, and the 38th Mississippi was listed as paroling 249 men. Adding the 43 men who were killed during the siege, plus those still in the hospital and on detached service who were not counted in the newspaper list, the regiment must have numbered nearly 300 souls when the siege began.41

The soldiers of the 38th Mississippi Infantry marched out of Vicksburg when their paroles were completed and as quickly as their starvation-weakened bodies permitted trekked to their homes and families. For a few precious months they were on furlough and free from the war. But all too soon the call of duty brought them back to battle in defense of the south.

1 Typescript copy of the diary of William L. Faulk, 38th Mississippi File, Vicksburg National Military Park, Vicksburg, MS.

2 Boatner, 874-876.

3 Official Records, Series 1, Volume 24, Part 2, 375.

4 Ibid.

5 Jones, Rank and File, 19.

6 Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, (New York: Charles L. Webster and Company, 1885), 1: 529.

7 Edwin C. Bearss, The Vicksburg Campaign, (Dayton, OH: Morningside House, 1986), 3: 761, 772.

8 Jones, History of Company D.

9 Bearss, The Vicksburg Campaign, 3: 770.

10 Official Records, Series 1, Volume 24, Part 2, 299-300.

11 Muster roll, CSR-MS, Record Group 9, rolls 62-65.

12 Faulk Diary, 19 May 1863, Vicksburg National Military Park.

13 Bearss, The Vicksburg Campaign, 3: 815-816.

14 Ibid., 820.

15 Official Records, Series 1, Volume 24, Part 2, 298.

16 Jones, Rank and File, 21.

17 James H. Jones to William Rigby, 29 May 1903, 38th Mississippi File, Vicksburg National Military Park, Vicksburg, MS.

18 Jones, Rank and File, 22.

19 Faulk Diary, Vicksburg National Military Park.

20 Record of Events, CSR-MS, roll 62.

21 Official Records, Series 1, Volume 24, Part 2, 376.

22 Eleazer W. Thornhill Memoir. Original is owned by Stanley Francis of Duncanville, TX. A copy is in the collections of the Old Court House Museum, Vicksburg, MS.

23 Jones, Rank and File, 25.

24 Clarke, 104.

25 Jones, Rank and File, 23.

26 William Faulk to William Rigby, 17 April 1903, 38th Mississippi File, Vicksburg National Military Park.

27 Eleazer W. Thornhill Memoir. Original is owned by Stanley Francis of Duncanville, TX. A copy is in the collections of the Old Court House Museum, Vicksburg, MS.

28 Undated statement by Captain Daniel Seal, 38th Mississippi Infantry File, Vicksburg National Military Park.

29 Warren Grabeau, Ninety-Eight Days. (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2000), 421.

30 Faulk Diary, Vicksburg National Military Park.

31 Eleazer W. Thornhill Memoir. Original is owned by Stanley Francis of Duncanville, TX. A copy is in the collections of the Old Court House Museum, Vicksburg, MS.

32 Faulk Diary, Vicksburg National Military Park.

33 Microfilm list of Paroled Prisoners, 38th Mississippi Infantry, Vicksburg National Military Park, Vicksburg, MS.

34 Muster roll, CSR-MS, Record Group 9, roll 62.

35 James H. Jones to Joseph Pendleton, 28 July 1908; Located in the Pension application of Joseph Pendleton; August 1914, Texas State Library and Archives Commission, Austin, TX.

36 Jones, Rank and File, 28-29.

37 Faulk Diary, 4 July 1863, Vicksburg National Military Park.

38 Boater, Civil War Dictionary, 877.

39 Eleazer W. Thornhill Memoir. Original is owned by Stanley Francis of Duncanville, TX. A copy is in the collections of the Old Court House Museum, Vicksburg, MS.

40 Undated statement by Daniel Seal, 38th Mississippi File, Vicksburg National Military Park, Vicksburg, MS.

41 Undated newspaper clipping from the J. L. Powers Scrapbook 1864, Catalog number Z742, Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

[End of Chapter 6]

Chapter VII

Reorganization

I am getting tired of being bound when I cannot go when I please I always wanted to be free.1

– Private Joseph Pendleton

January 4, 1864

While most of the 38th was on parole, spending precious time with their families, there was still a small band of men from Company A in the field fighting the Yankees. The detachment commanded by Lieutenant Gwin that was sent out on the Deer Creek Expedition experienced a considerable amount of combat in the time they were separated from the regiment, unfortunately there is very little documentation relating to this stalwart little band. Most of the information comes from the service records of the men who went on the expedition, and while this is a scanty record, it gives just enough material to piece together a framework of their journey.

No official documentation as to the size of Lieutenant Gwin’s force has been found, but Private Eleazer Thornhill of Company A wrote in a letter to his wife that the party consisted of one officer and thirty enlisted men. After the unit was cut off from the regiment when the siege began, the men were attached to Brigadier General Matthew D.

Ector’s Brigade, specifically to Pound’s Mississippi Sharpshooter Battalion commanded by Captain Merriman Pound.2 While attached to Pound’s Battalion, the detachment fought in the siege of Jackson, July 10-17, 1863, and had two men captured: J. J. McBride and Collen Sawyers. After the Confederate retreat from Jackson, Ector’s Brigade was sent as reinforcements to the Army of Tennessee in Georgia, and fought in the battle of Chickamauga on September 19-20, having three men wounded: Joseph E. Taylor, Henry C. McKinney, and Phillip J. Eubanks. In October the detachment was ordered to return to the 38th, then reorganizing at Enterprise, Mississippi.3

The process of bringing the 38th Mississippi back to life began on September 3, 1863, after a two-month furlough for the men. Major McCay received orders at that time to proceed to the counties in which the companies of the regiment were raised and begin rounding up his men and sending them to an exchange camp at Enterprise, Mississippi.4 Colonel Brent and Lieutenant Colonel Keirn were both unfit for service in the field because of their wounds, so command of the 38th passed to McCay, and with it the unenviable task of rebuilding the regiment after the mauling it took at Vicksburg.

The main obstacle in reorganizing the 38th after Vicksburg was simply getting the men back into the ranks after several months at home with their families. After weighing the pros and cons of returning to fight, many reached the same conclusion as Eleazer Thornhill who wrote: “By this time I had become very tired of war, and, to tell the truth, I did not like it from the very first. I had decided to remain at home just as long as possible.”5

The task of rounding up the wayward soldiers fell to the officers of the regiment, and typical of the orders they were given in regard to this duty was the following instruction to Lieutenant Tom T. Ball of the Price Relief from General Hebert:

…2nd Lieut. T. Ball of Company H 38th Regmt. Miss. Infty. will proceed without delay to the counties of Hinds, Newton & Madison in the state of Mississippi where his company was raised ready his men and bring them to this camp. He will apply to request of any cavalry command in that neighborhood to render him all assistance necessary…he will also provide the commanding officer of the cavalry lists & descriptions of the men.6

Hunting down men and forcing them to return to duty was not an easy job, as many of them had the aid of friends and neighbors to hide from the Confederate authorities. Eleazer Thornhill wrote in his memoir of the lengths he went to on one occasion to escape a roundup by Confederate cavalry:

We kept on down the swamp, stopping every now and then to listen. We could hear our persuers whooping to the dog. It was our intention, if possible, to get Pearl River between us. When we were crossing the road, four or five deserters saw us, and thinking we were cavalry, they put for the swamp. We came up with them and crossed the fence together, and sat down to get a little breath, as we were puffing like horses. We held a consultation and decided that we would not run any more, and that we would use the fence as a breastwork. It was well for the cavalry that they did not get through the swamp and follow us, for if they had come within range, some of them would have felt lead.7

The difficult job of rounding up stray soldiers continued throughout the winter of 1863-1864, and even though the 38th Mississippi was declared exchanged in December, it was several more months before the regiment was ready for combat operations.8 This fact was illustrated in a letter written by Captain John S. Hoskins to his wife in November 1863 in which he informed her that his company was forty-six strong, and this small number comprised nearly half of the regiment.9

As 1864 dawned, the rebuilding process continued in the 38th, but the New Year brought

some surprising news to the regiment. In January the department commander, Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk, ordered that the unit be designated the 38th Mississippi Mounted Infantry.10 Serving in this role the regiment would still fight on foot with standard infantry weapons as they always had, but now they would ride to get to the battle. In this capacity they could serve as a mobile strike force to quickly meet any enemy threat.

To meet Polk’s order, the first thing the regiment had to do was acquire enough horses to mount every man in the unit, but this was a difficult task at best because by this stage of the war, horses were very scarce, and civilians had learned to be very savvy at hiding their animals from Confederate impressment agents. This problem was partially alleviated by allowing the men to supply their own horses, and the government paid them for their use. A list of men in the 38th who supplied their own horses contained 139 names, so the effort was rather successful.11

Once the majority of the regiment was mounted, the unit received it’s first mission – the 38th was ordered to split into three detachments, commanded by Major McCay, Captain Jones, and Captain Estelle. McCay was given the task of sweeping the area east of the Pearl River for conscripts and deserters, and Captain Jones was ordered to Woodville with his detachment.12 Captain Estelle remained at Enterprise Mississippi with the third detachment that consisted of the men who had not yet received their horses. 2nd Lieutenant Tom Ball was one of the officers in Estelle’s detachment, and in March 1864 he wrote a report to the Confederate Adjutant General that is very revealing about the condition of the regiment:

My command ‘38th Miss. Infty.’ was captured at Vicksburg July 4, 1863. Not more than 150 of the enlisted men have ever reported at parole camp. All of these except some 20 have been mounted and ordered after absent men of the brigade where they are now I am unable to say. Capt. W. M. Estelle in command of the remainder my 20 men and two or three officers are on duty with the 37th Miss. Infty. at Pollard [Alabama] in this state.13

Chasing conscripts and deserters was a thankless job, but the 38th had its orders, and the men went to work on the task at hand. The mission was very frustrating, however, as the men they were hunting often had the support of the local community in evading capture. The ups and downs of the assignment were illustrated in a report filed by Major McCay in April in which he stated:

…since my return I have caught and placed in jail at Gallatin 7 deserters and two conscripts – (7 of these men are horse thieves)…I find two men here raising companies. One B. J. Foster – authority given by Col. Powers, is this right!! He had over twenty paroled men and is trying to hold them, they belonging to different commands – I arrested him and gave him one week to deliver the men up…I am glad to say, since my return large numbers of the troops are going to their commands, in preference to being caught & hope soon to finish with this county. Capt. I. N. Whitaker had some conscripts – claims to be an independent scout, and a few absentees are with him – this operates much against me, as his men stay but little in camp and all I arrest in his neighborhood claim to belong to him. Please give me instructions in regard to this command.14

The unpleasant duty the regiment had been assigned to finally concluded on April 3, 1864, when Major McCay was ordered to report to Brigadier General Lawrence Ross for new orders. Captain Estelle was directed to bring his detachment and rendezvous with McCay at Jackson, and Captain Jones remained in Southwest Mississippi attached to Colonel John S. Scott’s Brigade for several more weeks before rejoining the regiment.15

The trip to Jackson was very trying for Captain Estelle’s detachment, as the men were lacking proper clothing. In a requisition for the items his men needed, Estelle described the threadbare condition of his men:

I have marched some 100 miles and my men are barefooted and naked. I am now on the march to Jackson Miss. where I cannot get the articles called for. I have no Q.M. [Quartermaster], nor have I had one since I left the regt.16

Estelle requested for his men 20 jackets, 32 pairs of pants, 32 pairs of shoes, 19 shirts, 24 pairs of drawers, 20 hats, 22 pairs of socks, and 1 blanket.17

After Estelle reported to Major McCay at Jackson with his ragged detachment, the 38th received orders placing the regiment in a cavalry brigade commanded by Colonel Hinchie P. Mabry, of Brigadier General Wirt Adams Cavalry Division. Mabry’s Brigade was composed of the following units:

4th Mississippi Cavalry

38th Mississippi Mounted Infantry

Col. Harrison’s Regiment Cavalry

Robert’s Battalion Cavalry

11th & 17th Arkansas Mounted Infantry18

The units comprising Mabry’s new command had all seen hard service in the war and were low on manpower, poorly equipped, and sorely in need of reorganization. Fortunately, the Confederate military authorities chose the right man to whip the brigade into an effective combat force. The Colonel had already made a name for himself as a