By the fall of 1862, the Civil War was already taking a heavy toll in parts of Mississippi; in particular the Northern part of the state had already been occupied in places by the dreaded Yankee invader. The key point in north Mississippi was the strategic rail junction of Corinth, and on October 3-4, 1862, this little town was the scene of some of the most desperate fighting to take place in the Magnolia State in the entire war.

After the inconclusive Battle of Iuka, fought on September 19, 1862, Confederate generals Earl Van Dorn and Sterling Price agreed to unite their forces for an attack on the Federals in Northeast Mississippi. On September 22, their two armies joined at Ripley, Mississippi, and Van Dorn took command of the 22,000-man force as senior officer. Van Dorn believed

that a Union attack on Vicksburg was imminent, and he felt the best way to prevent it was to push the Yankees out of their staging area in west Tennessee. The first step in this plan was to take the town of Corinth from the Yankees, securing northeast Mississippi before advancing into Tennessee.

Union General William S. Rosecrans had 23,000 soldiers in and around Corinth, and his men had labored mightily to make the town an impregnable fortress. The Federals improved the earthworks originally built by the Confederates to defend Corinth, and then built an inner line of forts along the northern and western approaches to the city. There were seven of these forts, connected to one another by trenches. The names of these forts were batteries Robinett, Williams, Phillips, Tanrath, Lothrop, Powell, and Madison. When fully manned, these defenses could extract a very high toll from an attacker, as the Rebels were about to learn the hard way.

On September 30, 1862, General Van Dorn began marching his army toward Corinth under a blistering Mississippi sun. A heat wave was scorching the area at the time, making the march a living hell for the troops in the ranks. The trip was made even more miserable by the shortage of water along the route of march. James N. Carlisle, Sr., of the 37th Mississippi Infantry wrote of the journey to Corinth, “Through the driest section of the cotton states we endured the worst of distresses, thirst. What is comparable to this burning, parching fever? Lack of bread is sweet in comparison.” – The Daily Corinthian, October 8, 1962.

On October 3, 1862, the Confederate army attacked and overran the outer defenses of Corinth, forcing the Federals back into their inner line of forts. The 38th Mississippi Infantry was one of the Rebel units involved in this fight, and Lieutenant Colonel Preston

Brent of the regiment wrote an account of the successful attack: “…in a short time we had the enemy driven from their works and their guns in our hands, we did this in a short time, but nevertheless, we lossed a great many men in this charge for we did not fire a gun until we were within forty paces of their works the reason of this was that they had fallen a great amount of timber in front of their works and we were buisily a climbing over tree tops, but when we cleared the tree tops we made the Yankees pay for it.” – Beneath Torn and Tattered Flags: A Regimental History of the 38th Mississippi Infantry, C.S.A.

On October 4, General Van Dorn continued the attack, throwing his men against the inner forts defending Corinth. One of the focal points of the fighting was Battery Robinett, an earthen and log structure on a ridge near the Memphis & Charleston Railroad. Former Mississippian Colonel William P. Rogers was killed at the battery while leading the 2nd Texas Infantry; he has served in the 1st Mississippi Regiment under Jefferson Davis during the Mexican War.

During the battle, some of the Confederates managed to break through the inner Union defenses and enter Corinth, but they were quickly contained and then forced out by Union counter-attacks. With his force exhausted and his units shot to pieces after two days of bloody combat, Van Dorn was forced to call a retreat. The general was able to extricate his army from Corinth and make it safely back to Ripley, Mississippi, on October 6, 1862, when the campaign ended. Casualties were very high for both sides at Corinth; the Union had 2,520 killed, wounded, and missing out of 21,147 men engaged. The Confederates lost 2,470 killed and wounded, and 1,763 missing out of 22,000 engaged.

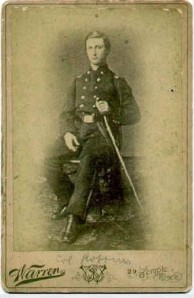

In the course of researching this article, I found a very good account of the battle written by George W. Driggs. regimental sergeant major of the 8th Wisconsin Infantry. This

account was written by Driggs shortly after the battle and was sent by him to his local newspaper, the Wisconsin Daily Patriot, and it was published in the October 15, 1862 issue. Driggs’ description of the battle is so compelling, I want to publish it in its entirety:

From Our Eighth Regiment Correspondent

THE LATE CORINTH BATTLE

ALL HONOR TO WISCONSIN TROOPS

A Complete List of the Casualties in the 8th, 14th, 16th and 18th Regiments and the 6th Wisconsin Battery

Appearance of the Field after Battle

Corinth, Miss., Wednesday, Oct. 9, 1862

Editors Patriot: –

I presume, ere this, you have seen an account of the great battle at Corinth, therefore I will not attempt to go into detail of what has already been written by others better qualified to describe such scenes as have been enacted here in the past few days. I have heard of ‘hard shell Baptists,’ and have been to ‘pumpkin parings,’ where jokes and hickory nuts were cracked pretty lively, but Lord, deliver me from the shells of the enemy, especially when they are in earnest about the ‘point of issue.”

The skeeters are very annoying, and so are the pesky fleas, but when you are obliged to flee before the enemy’s fire. It is still more annoying when you know that your reputation and your sacred honor are at stake. Patriotism, pure gem of manhood, biling over, oozing out at every pore, who dare skedaddle? I know of many that did run like wild cats, after a hot potater – men that were supposed to have been endowed by their Creator with courage enough to stand up to the rack, fodder or no fodder, and commissioned by the Executive of their favorite state with the expectation that they would help defend its honor.

I am happy to state that none from old Wisconsin, however, were seen to raise the ‘white feather,’ but all that were engaged in the fight, stood out nobly, doing honor to themselves and their country. There was no system or government head, but men and regiments rushed into the fight irrespective of brigade or division commanders (for such were not to be found, for shame!) and done nobly, driving the rebel hordes at the point of the bayonet back in the wild confusion. This was on Friday, the day of the first fight.

The combined forces under Price, Van Dorn and Lovell numbering about 42,000 made an attack on our outpost guard at Chewala, ten miles Northwest, driving them with great slaughter back towards this place. The ball had opened, rather unexpected, and for three hours or more an artillery fight was kept up on both sides with the most determined obstinacy, when the rebels becoming more bold and desperate made a charge through our lines and not until they had gained position under the brow of the hills overlooking the town from the Northwest were they compelled to retire.

They were bold enough however to attempt several times to capture a battery we had planted only a half a mile from the town, but the daring courage and bravery of our gallant Wisconsin 8th drove them from the field with great slaughter, and after contesting the ground for one hour and twenty minutes with the most desperate and unflinching determination on both sides the butternuts broke and ran for dear life, under shelter of the woods. Night closed the scene, and the fighting ceased, to be renewed in the morning with tenfold fury. – Price has told his men that they must take Corinth the next day, or go without rations. They were to be issued whiskey mixed with powder to make them brave and desperate, (so I was told since by one of the prisoners we took.)

Lieut. Colonel Robbins, 8th Wisconsin, was slightly wounded in the abdomen in the early

part of the action by a musket ball, the same having struck one of his pistol holsters on his saddle, tearing the pistol stock completely off. Major Jefferson, 8th Regiment, was also slightly wounded in the shoulder by musket ball, barely cutting through the skin – another shot struck his pistol in his hand, shattering it completely in pieces, without doing further damage. The major after having his wound dressed went out again on the field. These were close calls for them, I assure you.

About 2 1/2 o’clock, Saturday morning, the rebels having succeeded in planting a battery during the previous night, about half a mile to our front, opened on the town a continuous fire of shot and shell for nearly two hours. They were in such a position that the guns from our batteries and forts could not play on them. At daybreak, however, their position being discovered, our guns opened and soon dislodged them.

They became more desperate, and with a rush and a shriek the whole rebel force came down upon us, like so many beasts eager for their prey. Cannons were booming and musketry pouring their deadly volleys into the rebel ranks, but this did not seem to check them, on they came with the desperation of demons, until they had made a fearful charge up to the little fort, with one loud and frantic yell they made a dash upon it, but with the unerring aim of our gunners and the undaunted courage of our men, they were mowed down like grass before the scythe. 131 rebels were made to lick the dust while attempting to capture the fort. Never were the rebels more desperate, they succeeded in planting the rebel flag on our little fort three times, but not a single man of them was left to defend it. One of their Generals, whose name is Forester I believe, led the charge, and bore their flag twice to the top of the fort, but alas! he too paid the forfeit with his life. Daring, bold, desperate, and unflinching they led on their men, while shells were bursting all around them, and bullets flying thick as hail stones into their ranks. On they came rushing with furious vengeance into the town.

This was the time when the fight became general, it was 11 o’clock in the forenoon of Saturday, and at this time the shells came tearing through the buildings adjoining the one occupied by Lt. Col. Robbins, then wounded, and fearing for his safety, we placed him in an ambulance and went out a mile south of the town, out of the reach of danger.

Everybody was excited. Men, women and children were running here and there wild and frantic with excitement. Ambulances were driven in haste to the battle field. Couriers were running their horses at the top of their speed, and the continuous roar of cannon and musketry, all told that the fight was going on with unflinching determination on both sides, when at 12 – noon – the firing ceased, and the rebels were in full retreat, followed fiercely by our victorious army under Rosecrans. With what joy and satisfaction did this news spread through the lines after so desperate, and so hotly a contested struggle.

The rebels at one time were nearly conquerors, then to fall back and take up an inglorious retreat must have been a source of great terror to them. They were whipped completely, routed, disorganized and driven from the field at the point of the bayonet, but not until over one thousand of their men were shot down, and many more wounded.

When Capt. Williams’ mammoth siege guns opened their sulphurous mouths from the fort on the hill North of the town, and others at the same time from the batteries South of the town, their lines began to give way. Charge after charge was made, men were fighting with bayonets hand to hand and sword to sword, slaying and dying. The shrieking of the wounded could be heard amid the din and smoke of battle. Oh, this was terrible! No pen can describe the scene. The horrors of war here were fully and truly heartrending. The wholesale butchery of human beings – a description of which I will leave for future historians – the details are sickening to contemplate. Before one breastwork, where the 6th Wisconsin battery was stationed, the rebel dead actually lay in heaps. I counted 21 bodies, some with their heads shot off, others with their legs and arms completely blown off. There they lay, a ghastly bloody mass of human bodies, who had forfeited their lives for their reckless and daring spirit.

The weather was very warm and these bodies were much decomposed and the stench arising therefrom was indeed sickening – passing over the field, in groups cold and lifeless lay the bodies of dead rebels, the ground was strewn with dead, some clinching their muskets, and others who had apparently lingered long in their death struggles, had crawled through their gory mass of blood behind logs, and there, had breathed their last, poor beings, who became dupes to satisfy the cravings of a few leading aspirants for fame and whose treachery has brought thousands upon thousands to lick the dust, attempting to overthrow this Government.

On the hill in front of the little fort, (before mentioned) only half a mile and in plain sight of the town, lay the bodies of a large group of dead rebels, where they fell in attempting to capture our guns. I saw among the rest one Secesh Brigadier General, (I was told his name was Forester.) An artist was there taking a picture of the scene, while over a thousand persons had gathered there to witness the sight. I don’t think this artist should have been allowed the privilege of taking such a scene; this kind of of speculating ought not to be tolerated among civilized people.

After the battle, our wounded were brought in, and nearly every building in town converted into hospitals. During the engagements a general hospital was established in the outskirts of the town. Surgeons have all been busily engaged attending to the wounded and performing surgical operations. We have many wounded, but have as yet been unable to form a correct estimate of our losses. Many amputations have been made by Surgeon Thornhill and others. The secesh wounded were brought in, and were attended by their own surgeons, assisted by ours. The flight of the rebels was so hasty, that they left all their dead and wounded on the field. The pockets of the dead were all rifled before the retreat, whether by our men or the secesh I cannot say.

We are now in hot pursuit of the retreating foe, have overtaken them, and captured 140 of their wagons and a large number of prisoners. Price’s army is completely routed and cut to pieces, but Price is too shrewd to be taken himself – he looks well to that.

Gen. Hackleman was killed while leading his men before the enemy; Gen. Oglesbie was mortally wounded the first day in the lungs; Capt. Temple Clark is seriously wounded in the lungs, and Major W.D. Colman, A.A. General to Gen. Stanley, was mortally wounded in the lungs, from which he has since died. It is thought that Capt. Clark will survive. Col. Mower, who was temporarily in command of the 2d. Brigade, 2d. Division, was taken prisoner, but when the rebels began the retreat, he escaped to our lines, but was slightly wounded – ‘shot in the neck.’

A shell from a rebel battery burst in the office of the Tischomingo House, killing a wounded soldier.

Herewith find a list of killed and wounded in the Wisconsin regiments, as far as I have been able to gather them; they were mostly engaged in the fight of Friday – could not get a list of 17th Wis. nor 8th and 12th batteries.

Yours for publication,

G.W.D.

In his letter, Sergeant Driggs mentions that he witnessed a photographer taking photos of the Confederate dead that had been killed in the fighting around Battery Robinett. This is interesting because these photos still exist, and they are the only known photographs of Civil War dead on a Battlefield in Mississippi.

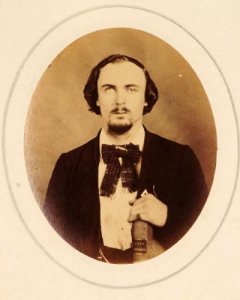

In his letter to the Wisconsin Daily Patriot, driggs incorrectly identifies the Rebel officer in the photo above as “Brigadier General Forester.” This was, in fact, Colonel William P. Rogers of the 2nd Texas Infantry.

In 1864, George W. Driggs published a book relating his experiences as a soldier during the

Civil War. Entitled Opening of the Mississippi: Two Years Campaigning in the Southwest, the book published a number of letters written by Driggs during the war, including the one he wrote about the Battle of Corinth. By the time the book came out Driggs must have learned the true identity of the Rebel officer he saw lying dead in front of Battery Robinette, as he changed the name of the officer in the published version of the letter from Forester to Rogers.

I have not been able to find much information on the post-war life of George W. Driggs; he did survive the war, and in November 1884 applied for an invalid’s pension from the United States government. Some time later his wife applied for a widow’s pension. Driggs’ book is available as a free download from Google Books, and I highly recommend it; the young Wisconsin soldier was a good writer, and he vividly brings to life his experiences during the Civil War.