It has taken MUCH longer than I anticipated, but the 2013 winner of the pick my blog article is finally finished! The winner of the contest was Sidney Bondurant, and he chose the topic: the 33rd Mississippi Infantry. I had planned to do a short article about the 33rd Mississippi, but fate intervened, and I found this remarkable memoir by John Snead Lamkin, captain of Company E, 33rd Mississippi Infantry. It was a long memoir, but I felt the content would make the effort involved worthwhile. I hope you like it.

Serendipity

noun

– luck that takes the form of finding valuable or pleasant things that are not looked for

Merriam-Webster.com

I have found in my years as an historian that serendipity plays an important part in my work. In the course of my research I don’t always find what I am looking for, but quite often I find very interesting things that I didn’t even know existed.

A perfect example of serendipity in action is the following memoir, Recollections of my Prison Life, written by Captain John Snead Lamkin and published in the Magnolia Gazette of Pike County, Mississippi. I stumbled across this treasure while looking for an obituary; it was the bold headline, “Recollections of my Prison Life,” that caught my attention, and a quick perusal of the article made it instantly clear that it was written by a Confederate veteran. What really intrigued me though, was that the article ended with the words “To be continued.” This meant it was not just one article, but a series of articles, which is somewhat rare. I find individual stories by Confederate soldiers in the newspapers all the time, but finding a multi-part series does not happen very often.

As I looked through the Magnolia Gazette to find the other articles by Lamkin, I was astounded to find that his writings went on and on and on. Lamkin began his series on July 30, 1880, and with only a few interruptions, continued with one each week until finally ending on February 11, 1881. What I had found was not just an article by Lamkin, but his entire memoir, printed out week by week, describing in great detail his last battle, in which he was captured, and his experiences as a prisoner of war in 1864 – 1865.

John Snead Lamkin’s memoir is important not because of its length, but because of its content. He was a keen observer and a very good writer, and his account of life at Johnson’s Island makes for fascinating reading. Lamkin’s description of prison life imparts to the reader an appreciation of the hardships of confinement and how the soldiers fought against boredom, loneliness, and the elements.

John Snead Lamkin was born on June 13, 1829, in Dooley Georgia, the oldest of the thirteen children of Sampson and Narcissa Lamkin. By 1860, he was living in Pike County, Mississippi, along with his wife Isabella, and his two children, Helen, age 2, and Lewis, age 10 months. John Lamkin listed his occupation to the census taker as lawyer, and listed the value of his real estate at $2,500, and his personal estate as $4,500. The Lamkin family also owned three slaves; John owned a male, age 35, and Isabella owned two females, one age 45, and the other age 13. – The Genealogy of the Lamkin family was accessed at: http://worldconnect.rootsweb.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=drphill&id=I338http://worldconnect.rootsweb.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=drphill&id=I338, June 7, 2015. The 1860 U.S. Census information for the Lamkin family was found in the Microfilm roll for Pike County, Mississippi; Roll: M653_589; Page 332. Information on the family’s slaves came from the 1860 U.S. Federal Census, Slave Schedules.

John S. Lamkin enlisted as a 2nd Lieutenant in Company E, “Holmesville Guards,” 33rd Mississippi Infantry, in March 1862. Promoted to Captain of Company E on September 24, 1863, Lamkin fought with his regiment at Corinth in 1862, Champion Hill and the siege of Jackson in 1863, and Resaca, New Hope Church, and Kennesaw Mountain in 1864. – Information taken from John S. Lamkin’s Compiled service record with the 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

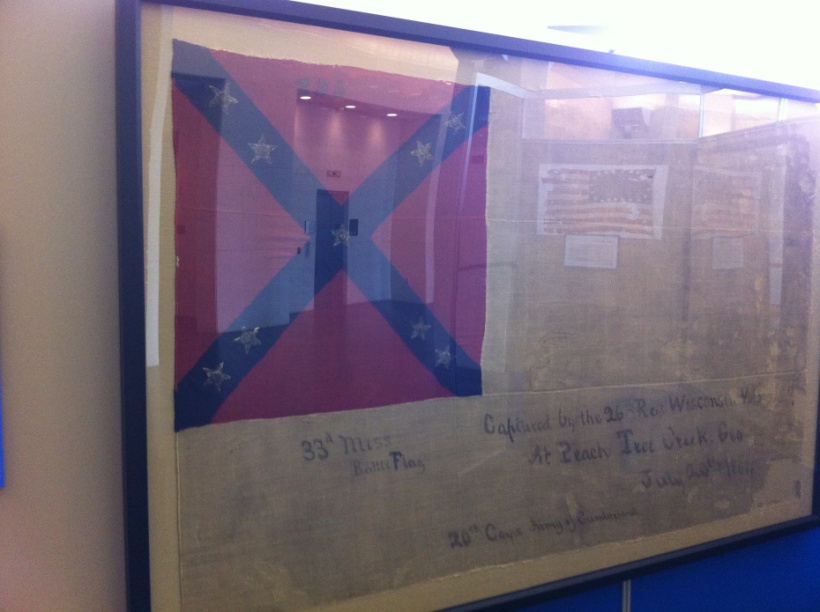

Lamkin’s memoir begins with the recollection of his final battle; Peachtree Creek, Georgia, which took place on July 20, 1864. The 33rd Mississippi Infantry was part of Brigadier General Winfield Scott Featherston’s brigade in this battle, which was composed of the following units: 1st Battalion Mississippi Sharpshooters, 33rd Mississippi Infantry, 3rd Mississippi Infantry, 22nd Mississippi Infantry, 31st Mississippi Infantry, and 40th Mississippi Infantry. Featherston’s brigade was part of Major General William W. Loring’s division, Army of Tennessee. – Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 3, pages 880 – 884.

The Battle of Peachtree Creek was a bloody one for the Mississippians in Featherston’s brigade, and I think the memory of the fighting there scarred Lamkin for the rest of his life. He begins his memoir with an account of this battle, and it serves as a riveting introduction to his story of life in a Civil War prison camp. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

Magnolia Gazette, July 30, 1880

Magnolia, Miss., July 22, 1880

Capt. J.D. Burke:

Dear Sir – I have just been looking through long disused documents – those which have now become musty with age. Among others I found one which I called at the time of penning it, “Recollections of my Prison Life.” On reading over some of it, I came to the conclusion that it might not be devoid of interest, to at least a portion of your readers. Most of the names mentioned in it are well known in this county. Some are living; some lie resting neglected on the field of honor, wrapped in their shrouds of imperishable glory; some perhaps, have passed away since the termination of the late “unpleasantness.” These “Recollections” were written while I was a prisoner of war, and all the scenes depicted were graven in my memory as with a pen of fire, and I know them to be correct and true as viewed from my stand point. They begin on the 20th of July, 1864, and running through a series of months, gives a sketch of prominent events which fell within my limited sphere of observation, up to April 20th, 1865. I have, and can have no “axe to grind,” in publishing this sketch, but only the desire to interest my friends. “What’s writ, is writ,” and I shall not change any of it, but let it go for what it’s worth, and will close the introductory remarks with the statement, that day before yesterday, sixteen years ago, I was “taken in out of the wet.” – Yours &c,

L.

[J.D. Burke was the owner/editor of the Magnolia Gazette]

Recollections of My Prison Life

By L.

I would like to commence these “Recollections” back at the beginning of my military career in the P.A.C.S., but while I fear that the time allowed me for the completion of the task – if my life should be spared me by the mercies of a kind Providence – will be more than ample yet, so huge seems the undertaking now, that I begin with the second chapter, to wit, my imprisonment.

I never think of the sanguinary 20th of July, 1864, but with a shudder. Yet, terrible as are the “Recollections” of that day, I will essay this task of depicting its horrors, and I think I shall keep to my purpose to the end. In doing this, I have an object in view. First; to fill up the moments of that time somewhat usefully, which would otherwise hang like a dead pall upon my hands, and secondly; that I believe (should I ever be liberated from this living tomb) there are those who will feel an affectionate interest in knowing what I have passed through and endured, while separated from them. Thus much by way of prelude.

At this writing I am a prisoner of war to the United States government, on Johnson’s Island, near Sandusky City, on the banks of Lake Erie, in Erie County, Ohio. I am in a large, open room, some fifty of us huddled indiscriminately together – a single stove in the middle of the room, but scantily supplied with wood; the cold winter approaching; no messenger, but for loved ones at home, whose lives are bound up in mine; and bad as the prospect is, for whose benefit I yet long to live. I am seated on the end of my little trunk, writing on a shelf, while my bunk-mate is gone to a cold, filthy kitchen to prepare our scanty meal of beef slops – the time being 4 o’clock p.m. We only get enough for two light meals in the day. Gaunt hunger is writing its lasting lines on the faces of all around me.

On the 20th of July, Hood’s whole force was lying behind earth works some fifteen miles above Atlanta, Ga., which works had been completed but a day or two – about the same length of time that Hood had been in command of that army. That noble old hero, Joseph E. Johnston, had just been relieved by the President of the Confederate States, from the command of that army. The relief of Johnston at this time took the whole army by surprise. So great was the astonishment that General Johnston should be relieved, that the various generals of his army (as the writer was informed) held a council of war on the subject, the result of which was that they addressed a note of remonstrance to the President by telegraph. The only reply to which was; “General Johnston is no longer commanding the Army of Tennessee,” &c.

As soon would his army have expected to hear of the relief of Gen. Lee, in Virginia, or the President as of their beloved leader, who Moses like had piloted them on from place to place, whithersoever the pillow of cloud should indicate by day and the pillow of fire by night, he though yielding territory in his onward march, was nevertheless thinning the enemy’s ranks by thousands – compelling them to scatter on their line of march which they had occupied with comparatively no loss on his side. His army all saw this and were conscious of the fact that never in all their campaigns had they been so well fed, clothed and provided generally. No wonder then that they looked upon him as their military Father and great moral hero. On the other hand, while they knew nothing against Gen. Hood yet, knowing less they loved him less.

About noon, the army lying as above described, received orders to march by the flank to the right along the breastworks. They were quickly in motion; for so long had they been in campaign, and so accustomed to this kind of movement, that but few minutes were required at any time to put that vast army of sixty thousand men in motion. We moved some mile and a half, as near as I could judge, and halted. My regiment, the gallant old 33rd Mississippi, resting on the summit of a very tall hill. Here we supposed we would rest as usual and await the flank movement of the enemy.

To Be Continued

Magnolia Gazette, August 6, 1880

In this, however, we were mistaken, for we had been in that position but a few minutes when our Brigadier General Featherston, received the order by the hand of a courier to carry his Brigade to the front – the whole army to move in echelon by Division. Sergeant William J. Lamkin happened to be standing a few yards in rear of the troops, and very near to where Gen. Featherston was sitting on his horse when the courier approached, and delivered him the order, and heard the order read. He immediately came up to the lines, and related to the writer the contents of the order, which you may believe produced a considerable sensation, but not so great a sensation as was produced a few minutes afterwards when we heard the clarion voice of Col. Drake communicating the word of command to his regiment. This was the last time that I have any recollection of having ever seen Sergeant William J. Lamkin. He was certainly killed during the battle.– William James Lamkin was the younger brother of John S. Lamkin. William was 3rd Sergeant of Company E, 33rd Mississippi, and his service record states, “Missing since July 20, in action at Peachtree Creek,” and “Killed July 20, 1864, near Atlanta, Ga.” The information on Lamkin comes from the Lamkin Family Genealogy on Rootsweb.com, and his Compiled Service Record with the 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

– Jabez L. Drake began his military career as a lieutenant in Company F, 33rd Mississippi Infantry, in 1862. He worked his way up through the officer’s ranks, and was promoted to colonel of the 33rd Mississippi on January 5, 1864. He was killed while leading his regiment at the Battle of Peachtree Creek, Georgia, on July 20, 1864. – Information from the Compiled Service Record of Jabez L. Drake, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

The General gave to the Colonel of his Brigade the necessary orders for the advance, which were the last orders ever given by him to many of us. We were thrown across the breastworks by our Colonels, not knowing what was expected of us. We had to go down the hill before mentioned, and through dense, tangled brush-wood, which had been cut down and interlaced to retard the progress of the enemy should he attempt to advance on our works. So difficult was it to go through this wood in order of battle, that Col. Drake gave the command, “By the right of Companies to the front – Battalion, by the right-flank, march.” In this order, we passed through the woods, a distance of less than half a mile, until we reached a field, where our pickets were stationed, through which ran a creek with abrupt, high banks, and wide marshy bottom, with tangled briars all the way across. There we were again brought into line of battle by the command, “By Companies into line, march.”

Then moved by the left-flank across this creek to unmask Brig. Gen. Wright’s Brigade, which we found on our right in front, partly lapping over ours. Having crossed the creek, we were again moved towards the front, but soon found obstacles in the shape of briars, &c., that the three right companies could not easily surmount; so they were thrown back by the command, “Three right Companies, obstacle.” This took all companies on my right, mine being the fifth company, one of which was on picket. Thus arranged, we were again started to the front, and very soon were compelled to cross another bend of that difficult creek; this we did in the utmost disorder, for it was impossible to keep men in line in such a place; and by the time I was myself over, on looking about, saw my company scattered over a large space. I devoted myself as rapidly as possible to forming my company into a good line again.

By this time the men began to sniff the battle breeze, and they began to rush headlong onwards, encouraged to the most daring exhibitions of courage by my fiery spirited Lieutenants, who at that moment knew no fear, and were followed by men equally intrepid. Occasionally we heard the encouraging voice of our gallant Col. Drake; and then the advance of our men through morass, brambles, plowed fields, and over fences, became so rapid that I, who had been weakened almost beyond the power of exertion, by that dreadful plague of the soldier, chronic diarrhea, found the utmost difficulty in keeping up with them. The companies which had been thrown back on my right never did come up into their places, thus leaving a long, open space on my right, which was the cause of so much of the disaster that subsequently attended us. We had to pass through a pretty large plowed field just before approaching the enemy’s pickets, which were posted on the top of a hill, some thirty yards outside of the field. On going up the hill and approaching the fence which surrounded this field the enemy’s artillery poured an enfilading fire into us from the left, which completely swept the field. Here one of my litter bearers asked me if he should take Orderly Sergeant Richmond and Private Marion Lee to the shade? Alas! The noble boy, T.D. Richmond, or Dilly as we called him. I asked what of them?, and was informed that they were both wounded. I ordered them to the rear immediately. I did not learn how they were wounded, and have not seen, and only heard of them once since through the papers. – Francis Marion Lee was a private in Company E, 33rd Mississippi, enlisting on March 22, 1862, at Holmesville, Mississippi. He was “Wounded and sent to hospital, July 20, wounded slightly.” – Compiled Service Record of Francis Marion Lee, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

– Thomas Delavene Richmond was the 1st Sergeant of Company E, 33rd Mississippi. He enlisted on April 30, 1862, at Holmesville, Mississippi. He was “Wounded in action on 20 July and sent hospital, wounded slight.” – Compiled Service Record of Thomas D. Richmond, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

As fast as we got to the fence we laid down, thus giving a few moments for rest and to collect the scattered men in line. Soon we heard the clarion voice of Col. Drake again calling out, “Forward, men, Forward!” The Regiment was up in an instant, and mounting the fence. There was a gap in the fence to my right, through which I threw my company, “By the right-flank, by file-left, march.” We then saw the enemy beginning to fly from their picket line. After clearing the gap I again brought my company “By company into line, march.” Just then I saw a blue-coat in great haste ascending the opposite hill. I pointed him out to Private Adam Bacot who was near me, and told him to draw a bead on him. He raised his rifle to his face, holding it poised for an instant, when its clear tone rang out to swell the rattling tumult all around, and the poor fellow tumbled on his face to rise no more (I suppose), until the resurrection morn. He must have been hit in the back. – Adam Bacot was a private in Company E, 33rd Mississippi. He enlisted March 22, 1862, at Holmesville, Mississippi, and was captured and paroled at Corinth in October 1862. Compiled Service Record of Adam Bacot, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

Just previous to this, Bacot pointed out a man to me whose head and shoulders were visible behind the enemy picket works, and asked me if it was one of our men or an enemy, and if he should shoot him. I could not distinguish the color of his dress and told him not to shoot, thinking some of our men might have got there ahead of us. Just then a bullet whistled by our ears and we saw the tip of a Yankee blouse fluttering in the breeze. As its wearer was flying down the steep hill which sheltered him from our view. This is believed to be the same man who again came in view as he ascended the next hill, and whom Bacot shot. Turning my eyes to the left, I saw Lieut. Level, the ensign of our regiment, full thirty yards in advance of the line rushing madly on, holding aloft and waving most furiously and defiantly our beautiful battle flag, the stars and bars. – Edwin Francis Leavell enlisted March 1, 1862, as 5th Sergeant of Company H, 33rd Mississippi Infantry. Appointed regimental ensign in early 1864, Wounded in the right jaw and shoulder at Peachtree Creek, Georgia, Leavell was captured by the Federals and sent to the hospital. – Compiled Service Record of Edwin F. Leavell, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

Suddenly I saw the beautiful emblem and it proud and brave bearer tumble to the earth. Oh! How my heart bled to see that noble man, that beautiful flag go down! But animated by a soul of flame which death alone could extinguish, the next instant he was seen crawling towards the enemy on one hand and knees dragging his beloved colors after him. Ah! The death hail was rattling around us then, and many a noble man there fell to rise no more; yet, many a death dealing blow was struck by us in return as we rushed despite all obstacles, on, right on to the front. I saw our beautiful flag no more, but was told that Silas C. Rushing snatched it from the ground and bore it proudly on, until he too, paid the penalty for his gallantry with his life’s rich blood. Again, it was snatched up by some one and borne onward until he too was shot down. Thus thrice was our colors prostrated, and as often rose, when alas! they fell to wave no more over the brave hearts that were want to march beneath its beautiful folds, on to the acquisition of their dearest rights. – Silas Cyrus Rushing enlisted in Company E, 33rd Mississippi Infantry, on March 22, 1862, at Holmesville, Mississippi. Wounded in action at the Battle of Peachtree Creek, Georgia, and captured by the Federals. Sent to Camp Douglas prisoner of war camp in Illinois, Rushing died of Typhoid Fever on February 19, 1865. – Compiled Service Record of Silas C. Rushing, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

To Be Continued

Magnolia Gazette, August 13, 1880

About this time the gallant Drake fell, but the Regiment knew it not, except in the lack of order in their onward charge; but they did charge madly onward, and in that throng of brave spirits, not one organized company exceeded “Co. E,” for they went as far as he who dared go farthest. But we had no support on our right as far as the woods would let me see – a distance of about 100 yards. We charged down the hill on which stood the force above described, and up the next from the summit of which we could see where most of the mischief proceeded from. On the ascent of the next hill side, and beyond a ravine appeared the enemy’s breast-works of rails, evidently, hastily thrown together, from which they had full play at us every time we got on an eminence.

Notwithstanding the murderous volleys poured into us from their works, and from the ravine nearer by, and also from a battery which seemed but just to have got into position on the line of their works, we moved rapidly forward, the gallant little “Co. E,” as I believe, leading the van, until we reached a deep trench running parallel with our line of march, and about fifteen paces from the ravine spoken of. I jumped into this because I could not jump across it, and found it almost immediately filled with my brave boys, who hovered all around me, and seemed to desire to lose no time, for they loaded and fired as rapidly as they could, and when they would sink exhausted, a word of encouragement would cause them to make still another effort, to shoot a hated foe. I soon ascertained however, that the enemy was taking advantage of the gap on my right to flank us, and I ordered my boys, all who could, to return. I then for the first time ascertained what our condition was.

My brave brother Abner had received a minnie ball in his bowels and was supported by Bacot, who also deported himself with consummate coolness and bravery. Lucius M. Quin, who was a corporal, and a mere boy, and who had endeared himself to me by soldierly qualities, came to me holding up his (left I think) arm bleeding, told me that his arm was shivered all to pieces, and asked me for God’s sake not to leave him in the hands of the enemy. I promised him I would not, and immediately helped him out of the ditch, which was hard to climb. Corporal Raiford Holmes, another noble boy, came also begging me not to leave him. This I also promised. He was shot in, or about the hip-joint, dangerously. His brother, Sergeant David Holmes and I helped him out of the ditch, but he could not travel and was taken down again. – Abner Lewis Lamkin was the younger brother of John S. Lamkin. He enlisted in Company E, 33rd Mississippi, on March 22, 1862, at Holmesville. He was “Killed in action, July 20, 1864, at Peachtree Creek.” – Lamkin family genealogy at Rootsweb.com, and information on his military service is from Lamkin’s Compiled Service Record with the 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

– Corporal Lucius Monroe Quin enlisted in Company E, 33rd Mississippi, on April 10, 1862, at Holmesville. He was “Wounded in action 20 July and sent to hospital, wounded severely.” Quin survived his injury and the war, dying in Pike County on November 4, 1909. – Compiled Service Record of Lucius M. Quin, 33rd Mississippi Infantry, and his tombstone information from Findagrave.com.

– Corporal Raiford Holmes enlisted in Company E, 33rd Mississippi, on March 22, 1862, at Holmesville. Holmes was shot in the left hip during the Battle of Peachtreee Creek. Captured by the Federals, he died in the Field Hospital, 3rd Division 20th Corps, on August 24, 1864. – Compiled Service Record of Raiford Holmes, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

– Sergeant David Holmes enlisted in Company E, 33rd Mississippi on March 22, 1862. He was captured at the Battle of Peachtree Creek and sent to Camp Chase prisoner of war camp in Ohio. He died of Pneumonia on January 31, 1865, and is buried in grave 978 at Camp Chase. – Compiled Service Record of David Holmes, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

Then came the hardest part of all: my gentle brother, whose wound I thought was fatal, implored me not to leave him. I directed Bacot to do the best he could for him, and he said, ‘Captain, I don’t know what to do; he cannot walk.’ Oh! my soul sank within me then. Judge me ye Martinets; what was my duty then? Had I not stopped to assist my poor boys, at their earnest entreaties, perhaps I might have got back; but I think I could not, for of all those who were with me in the ditch, and started back, I know of but two who got back, and they were Quin and Bacot. Was it my duty to start and leave my boys? Could the pleading eyes of a dying brother furnish no reason for a minute’s hesitation? And a minute was all I had, but it was a minute heavy laden with consequences to me, for by the time I had said a few words to him, two of the enemy came over the little ridge that separated the ravine from the ditch in which we were.

As they came up, seeing my chances of escape cut off, Lieut. Ratliff, Sergeant Holmes and I, who were standing close together, announced our surrender as prisoners of war. As we did so, the foremost fellow, who I suppose was an officer, commenced fumbling rapidly in his belt, then jerking out his pistol, he said: ‘You son of b—h,’ and leveled it at the group of us (as then supposed) and fired, but God who holds even bullets in his hand turned aside once more the messenger of death, and he missed us. I then looked rapidly around for a loaded gun, but could find none but empty ones. Had I come across one, I suppose I would have tried to kill him. Frank Ware, who I did not know was there, it afterwards transpired, had snatched Lieut. LeNoir’s pistol and fired at the other one, striking him in the upper part of the arm. The Yankee who had (as we supposed) fired at us ran back, but the other remained with us and talked kindly to us. Lieuts. Ratliff and Miskell, about the time of the firing above mentioned, attempted to get back – Ratliff remarking that ‘If I have to be shot down after I have surrendered, I might as well be shot in trying to get back.’ Bacot and Morgan also started back, and I think another one but I cannot distinctly remember. – 3rd Lieutenant Warren R. Ratliff enlisted in Company E, 33rd Mississippi, on March 22, 1862, at Holmesville. He was killed in action at the Battle of Peachtree Creek on July 20, 1864. – Compiled Service Record of Warren R. Ratliff, 33rd Mississippi Infantry. In his history of the 26th Wisconsin Infantry, author James S. Pula wrote of the following incident in the wake of the Battle of Peachtree Creek: “Making his way to the field hospital, [Frank A.] Kuechenmeister picked up a cedar canteen inscribed ‘W.E. Ratcliffe, 33d Mississippi Infantry.” – The Sigel Regiment: A History of the Twenty-Sixth Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry 1862-1865.

Note – I have since come to the conclusion that the fellow did not shoot at us, who were standing together at all, but at Ware, in retaliation for the shot fired at them, by him, and that this drew forth the exclamation of the fellow, who fired the shot. At all events, this was the cause of Ratliff’s death, for he would have remained a prisoner, but for that shot. I then for the first time found Lieut. LeNoir wounded in the calf of his leg, behind an angle of the ditch, and Frank Ware with him, who had also been slightly wounded. I was gratified at a remark made by Lieut. LeNoir, for he then and there testified to the cool, deliberate bravery of Abner Lamkin. Said he had watched him and never saw a man bear himself more nobly. I suppose the reason Lieut. Ratliff attempted to escape was the (seeming) act of treachery of the fellow who (as we supposed) fired at us after our surrender. At all events, I never again saw him alive. – Private Benjamin F. Ware enlisted in Company E, 33rd Mississippi, on July 13, 1863, transferring to the regiment from the 4th Mississippi Cavalry. He was captured at the Battle of Peachtree Creek, and sent to Camp Douglas prisoner of war camp. Ware was released from the prison on June 17, 1865.

– 1st Lieutenant George B. Lenoir enlisted in Company E, 33rd Mississippi Infantry, on March 10, 1862, at Holmesville, Mississippi. Wounded in action and captured at the Battle of Peachtree Creek, Lenoir was exchanged at Rough and Ready, Georgia, in September 1864. Apparently he was thought dead for awhile after his wounding, as his service record also states he died in a Federal hospital on July 25, 1864. Lenoir managed to survive the war, surrendering in North Carolina on April 28, 1865. He died on October 1, 1911, and is buried at Hope Hull Lenoir Cemetery in Marion County, Mississippi. – Compiled Service Record of George B. Lenoir, 33rd Mississippi Infantry and his listing from Findagrave.com.

Soon after getting into the ditch, Lieut. Miskell looked across the little ridge in our front, and saw men’s heads in the ravine beyond. He asked some one near if they were our men, he said that, ‘if any one else can go there we can,’ and started; but a better scrutiny showed him they were not our men, and he did not go. I did not see him when he started back. By this time the Yankees commenced pouring over us in numbers. Some of whom when they saw us cried out in Dutch jargon, ‘kill dem, kill dem; knock dem on de head,’ &c. One who had stopped with us told them if they did it, it would be over his dead body; they were his prisoners and should not be hurt. After they passed us he apologized saying: ‘They were none of our boys, and nothing but Dutch anyway.’ – 2nd Lieutenant Richard A. Miskell enlisted in the 33rd Mississippi Infantry on March 22, 1862, at Holmesville. He was initially listed as “Missing in action since July 20, 1864 in action at Peach Tree Creek.” It was later noted that Miskell was “Killed July 20, 1864 near Atlanta, GA.” – Compiled Service Record of Richard A. Miskell, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

To Be Continued

Magnolia Gazette, August 20, 1880

I then devoted myself entirely to the care of my poor brother. I took his head in my lap, but could not arrange him very comfortably. He talked to me incessantly. I said something about being apprehensive that I would be blamed for remaining with him, but he said, no indeed, no one could be so hard hearted as to blame me for staying with my dying brother. He said he would not have had me leave him for a thousand worlds. He talked of his father, mother, brothers and sisters. Called me his good brother, and said he would rather I would be with him then than any one in the world. Asked Serg’t Holmes (who was nursing his brother) and me to pray for him, which we did. He heartily responded. I asked him if he was prepared to die. He said he felt no consciousness of guilt. He was very thirsty and I used up all the contents of my canteen, his and Holmes,’ after which the Yankees kept me well supplied with water. He wanted me to continue pouring it on and around his wound. I tried to dissuade him from talking, fearing it would fatigue him too much. He was very restless, and once when I tried to place him in an easier position his bowels gushed out at his wound. I then lost all hope of his recovery, for I saw the hole in the intestines. He spoke of his knapsack, telling me where to get it, and took some little trinkets from his pocket, asking me to take them to his mother. I have them yet.

In this way he survived perhaps an hour and a half, when he died calmly and peacefully, as he had lived, and I believe and hope went to Heaven. Once in the time he remarked that he knew a wound was painful, but did not know it hurt so bad. Holmes and I laid him out as neatly as we could, and I wrapped him up in my blanket. An Acting Major at my request promised me that he would be buried on the spot where he lay, and a board with his name and command thereon, placed at his head. The Yankees allowed me to watch by his side until about 9 o’clock at night. Previous to this time, however, I went in charge of a guard to walk over the field and see who I could discover. Some eighty yards back of where I was captured, I found Lieut. Miskell on his elbows and knees, drawn up, his face between his arms, cold and dead; Lieut. Ratliff on his back, the contents of his haversack scattered all around him, already dead. Lewis N. Ellzey, wounded, he told me of the death of John Harvey, but the Yankees would not let me go further, nor allow me more time, as they were fast erecting their breast works on top of this hill. If I could have looked further I would probably have been able to a certainty to relieve all doubts as to the fate of Brother William.

– Private Frederick C. Buerstatte served in Company F, 26th Wisconsin Infantry, and his regiment was engaged with the 33rd Mississippi during the Battle of Peachtree Creek. On July 21, 1864, he wrote in his diary, “This morning our regiment, after a sleepless night, had to bury the dead Rebs which laid before our regiment. They were all from the 33rd Mississippi Regiment. Our regiment lost 9 dead and 36 wounded. We buried over 50 Rebs, among them Colonel Drake and most of the officers of the 33rd Miss. Regiment.” An online transcript of Buerstatte’s diary can be found at: http://www.russscott.com/~rscott/26thwis/fredbdia.htm.

– Lewis N. Ellzey enlisted in Company E, 33rd Mississippi, on May 1, 1862, at Holmesville. He was wounded in the right thigh and captured at Peachtree Creek and sent to Camp Douglas prisoner of war camp. Ellzey died at Camp Douglas of Typhoid Fever on January 13, 1865. – Compiled Service Record of Lewis N. Ellzey, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

– Private John T. Harvey enlisted in Company E, 33rd Mississippi, on April 10, 1862, at Holmesville. He was killed in action at the Battle of Peachtree Creek, July 20, 1864. – Compiled Service Record of John T. Harvey, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

Still later in the evening I prevailed on them to permit me to visit Lieuts. Ratliff and Miskell again to point their bodies out, and obtain their promise to give them a descent burial where they were lying. This they promised, but on the occasion of each visit, it being dark (or only star light) I could not tell nor was I allowed time to ascertain how they were struck. Raiford Holmes had been carried off and his brother, David Holmes permitted to stay with him. About ten or eleven o’clock, I was carried to the rear, being compelled to bid a final farewell to all that was mortal of poor Abner, whose fate, to die, so young, so good, so loved, so brave, was enough almost to break my heart. Frank Ware was taken with me, and we were not separated until we arrived at Louisville, whence the privates were taken to Camp Douglas, the officers to Johnson’s Island, where possibly their bodies may be reposing when the last trump shall sound. To wake the sleepers under ground.

To Be Continued

Magnolia Gazette, September 3, 1880

Lieut. Lenoir was not removed up to the time I was taken away, and I do not know where he nor the Holmes’ now are. I will, in the proper place, mention all that I have since heard of them. In going to the rear, I passed the spot where they had collected our wounded, and oh! what a heart-rending scene it was when the wounded knew it was I who was passing. There were several of my brother officers, and several privates from my own regiment. A Lieut. Kennedy, a good fellow called to me, ‘Captain come here; I am dying,’ said he ‘give me your hand; I bid you an affectionate farewell.’ He then mentioned some indifferent matters to tell his friends if I should see them. Lieut. West also spoke to me. Lieut. Level, the brave ensign of the regiment, whom I previously mentioned, called to me and said: ‘Oh, Captain, I am shot all to pieces.’ He was hit in the face and shoulder. Last, but not least affecting to my feelings, my own boys who had trod so many weary miles, contested so many well fought fields, and borne so many hardships subject to my lead, began calling on me. There was Lewis Ellzey, whom I previously mentioned, and Osborne, of whose fate I knew nothing until that moment. He told me that his wounds were of a dangerous character and he thought he could not survive them. I think he died subsequently. – 3rd Lieutenant Simeon J. Kennedy served in Company A, 33rd Mississippi Infantry. He was wounded and captured by the Federals at Peachtree Creek on July 20, 1864. There was another notation in Kennedy’s service record that he was “mortally wounded.” – Compiled Service Record of Simeon J. Kennedy, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

– 3rd Lieutenant Andrew G. West served in Company G, 33rd Mississippi Infantry. He was killed at the Battle of Peachtree Creek, July 20, 1864. – Compiled Service Record of Andrew G. West, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

– Private Lawrence Osburn enlisted in Company E, 33rd Mississippi, on May 31, 1863, at Jackson, Mississippi, as substitute for another man. He was killed in action at Peachtree Creek on July 20, 1864. – Compiled Service Record of Lawrence Osburn, 33rd Mississippi Infantry.

I spoke what words of encouragement I could to them, but my heart was too full to say much, and it was a relief when the

Yankee guard hurried me onward. I omitted to mention in the proper place, that it was the 20th Connecticut Regiment, Ward’s Brigade, Hooker’s 20th Army Corps, that we fought, and that took me prisoner. On the occasion of my second visit to the bodies of Miskell and Ratliff, I fell in with the acting Major again who asked me if I was the Captain he had previously seen. I told him I was, he then requested my sword, which I presented to him. He deported himself very gentlemanly towards me, as did many of the guard. After this the Major of the regiment – acting Colonel – came and sat down with me, entering very delicately into a discussion of some of the questions that separated us. He was a man of polished manners and fine address, and appeared in the imperfect light to be a mere boy.

To resume, I was being conducted past Gen. Ward’s head quarters to the ‘Bull Pen.’ The General having been informed that a Captain was in tow, sent for me. When I entered his tent (fly rather) he raised up from his cot and spoke to me very politely, at the same time ordering a chair for me. We held a conversation of some half hour in length, during which I, having caught the Yankee style, asked him nearly as many questions as he did me. He did not ask me the old hacknied question as to the strength of our army, but some fellow sleeping near me did – putting his questions in several different forms – some of them I declined answering without giving a reason, and some, for the best of reasons, that I did not know. After which the General spoke rather petulantly I thought, saying he had never yet seen once who did know the strength of their (our) forces. I took this as a rebuke to the individual (perhaps his A.A.G.) who had asked question so little likely to be answered. In answer to some of my questions, the General informed me that he had been in the old congress and was distantly connected with Matt Ward (whom all remember), had known Gens. Featherston, Barksdale, &c., and indeed all our political generals, and thought there was more of the politician than the military man about many of them &c. He stated that he though we would soon be exchanged, as the only obstacle seemed to be the ‘nigger,’ and that both parties had agreed to ignore that until they got through with the white folks. This alas! has proved to be a delusion by the poor prisoners on both sides. I was then sent to the guard house, where I found several officers and a good many men from my brigade – several of the men being from my regiment. I laid down to sleep for the first time in my life a prisoner. In a very short time I awoke and the sun was shining down on me. Thus ended my first day of imprisonment. The next day being no so pregnant with consequences, will not require so much tediousness in description. – The “General Ward” mentioned by Lamkin was Brigadier General William T. Ward, who commanded the Third Division of the XX Corps, Army of the Cumberland. “Matt Ward” may have been Matthias Ward, who was a United States Senator from Texas in 1858 – 1859. Information on Matthias Ward found at: https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fwa50.

To Be Continued

Magnolia Gazette, September 10, 1880

The morning of the 21st dawned gloriously on me, but alas! it brought no sunshine to my heart. I traded a piece of tobacco to a Yankee for a cup of coffee and some crackers. This was my breakfast; but I had plenty of corn bread in my haversack, a part of which being mouldy, I threw it away. I was treated kindly enough by the soldiers at the front, for they knew how to treat a manly foe then. All my maltreatment was reserved for the cowardly miscreants to inflict who are far in the rear.

Pretty soon, ‘Fighting Joe Hooker’ came prancing by us on his gay gelding. He is a man of fine appearance; keen and sharp looking: red face; aquiline nose; light hair, weighing apparently about one hundred and eighty pounds. It was with a heavy heart that I soon after that, in company with the other prisoners took up the line of march for Gen. Thomas’ head quarters. Arrived at some body’s quarters, were stopped, when the rolls were made out and verified; and then we were sent on a distance of two miles to Gen. Thomas’ quarters, where we found him in a state with all the business paraphernalia of his department, and many more prisoners, near 350 in all. Then our roll was again called, rations issued, and all of us quartered for the night, (i.e.) surrounded by a guard. I found among them Frank Martin, son of J.T. Martin, of Pike, also an assistant surgeon of his (45th Mississippi) Regiment. The assistant surgeon was sent back from there and Martin was carried on with us to commence his second term of imprisonment. – Private Frank M. Martin enlisted in Company E, 3rd Battalion Mississippi Infantry, on November 11, 1861, at Natchez, Mississippi. The 3rd Mississippi Battalion was later designated the 45th Mississippi Infantry. Martin was captured at the Battle of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, on January 1, 1863. Sent to Camp Douglas prisoner of war camp in Illinois, he was paroled on March 30, 1863. He was captured for the second time near Atlanta on July 20, 1864, and sent back to Camp Douglas. Martin was discharged from the prison on June 17, 1865, after taking the Oath of Allegiance to the United States. – Compiled Service Record of Frank M. Martin, 3rd Battalion Mississippi Infantry.

Early on the morning of the 22nd, we were formed and commenced our march of fifteen miles to Marietta. This we completed before night some time, although the road was exceedingly dusty, water scarce, and weather warm. That night we were quartered in the courthouse, on account of a shower of rain that came up, and our condition was exceedingly uncomfortable on account of the dense crowd of us; and with all due deference to my brother prisoners, I will say that I have been much more crowded by them ever since than I like.

About 9 o’clock on the 23rd we were marched out in order – officers in front – to the depot, where after some delay we were placed in the cars, which were a dirty box for the officers, and mostly open slatted sided cars for the men. It was amusing to see the maneuvers of a couple of young cavalrymen to pass themselves of as officers. They were a little doubtful about coming out and saying they were officers, and yet thrust themselves among the officers, thinking thereby to get better quarters and accommodations. But the test question came plainly from the Yankees after awhile and they had to own up and take back seats.

At length we were off, and I felt myself fairly on the way to Yankee land. We ran all that day, night and until about half an hour by sun next morning, when we took up at Chattanooga. The guard with whom we started followed us up to this point where they turned us over to the provost marshal and a new guard. The old guard treated us humanely, but the new were kinder still, (i.e.) after they started again with us. At Chattanooga we were put into a room, so much crowded that all of us could not lie down at night. It was literally alive with vermin; filth too abounded to a disgusting extent. The occupants of the room were Yankee deserters, suspected citizens, bushwackers, guerrillas, horse thieves, murderers, &c. Such was the companionship that we were thrust into.

The general appearance of the town was much improved from what it was a few years ago when I saw it. The streets were turn-piked, many neat houses were erected, stores, groceries, and confectionaries were in full blast; ‘But the trail of the serpent was

over it all.’ On all the heights surrounding the place frowning battlements stood out in bold relief; while here and there on the sides of the hill, a dark cloud appeared, supposed to be encampments of Negro troops. We stayed two nights there. About 8 o’clock on the 25th, we were taken from our dreary abode to the depot, where we awaited the cars, which were ready for us about 1 o’clock. During our stay there I saw the Yankee General Rosseau. He is a burly looking man, of Dutch appearance; nothing distinguishing about him. – “Yankee General Rosseau” was Major General Lovell Harrison Rousseau, who commanded the districts of Nashville and of Tennessee, and had his headquarters at Murfreesboro, Tennessee. – Generals in Blue, pages 412-413.

Several privates were here said to have manifested their wish to take the oath, and it was said they were to be taken north of the Ohio River and released. I do not know what became of them. I am glad there were no Mississippians among the number. Near one o’clock we were off again as fast as steam could bear us, to a bleaker clime. Ran all night, passing through Murfreesborough, some time during the night. Next morning about sun rise, we found ourselves at Nashville, where we were incarcerated in the penitentiary. This was my first appearance in a penitentiary as a prisoner; but our treatment was a considerable improvement on the Chattanooga calaboose. Many of the officers and men being Tennesseans [had] received small sums of money, provisions, and clothing. Here we remained over night.

About 10 o’clock on the morning of the 27th, we were again started to the depot. On our march thither, a distance of half a mile or more, several little incidents occurred which affected me some. Once as I was marching along near the head of the column, I observed a buggy meeting us, driven by a large, fine looking old lady, having a little boy by her side. I, of course, paid but little attention to this, and should perhaps have forgotten it in a few minutes; but just as they got opposite to us – the little boy – his face and eyes all aglow with excitement, eagerly clapped his little hands and seemed bursting with the intensity of his emotion; and I at the same time saw the old lady put her handkerchief to her eyes. Just then I observed a young Tennessean by my side (who had endeared himself to us all by his high and chivalrous bearing and noble and generous disposition) shudder and put his handkerchief to his eyes. We marched in one direction, and the buggy passed on in the other. At length he remarked: ‘I hardly thought he would have known me; my dear little brother! and my mother too! It has been so long since I saw them – three years now and he was a little fellow when I left him.’

We turned and gazed after the buggy, and the old mother whose heart was bursting to embrace her much loved oldest boy (who was the prop of her declining years), was waiving her handkerchief. But few knew the wealth of love conveyed by that wave, yet he for whom it was intended understood it all. She then turned her buggy back and drove close by us again. They could see each other and cast loving looks at each other – that weeping mother, that noble, sorrowing son, and that child brother. But alas! that was all that our Argus-eyed guards could not prevent. This young officer’s name is Andrew Allen. He is in this prison now. – “Andrew Allen” was probably Lieutenant Andrew J. Allen, ensign of the 2nd (Robison’s) Tennessee Infantry (Walker Legion). Allen was captured on July 20, 1864, near Atlanta, Georgia, and sent to Johnson’s Island prisoner of war camp. – Compiled Service Record of Andrew J. Allen, 2nd (Robison’s) Tennessee Infantry.

To Be Continued

Magnolia Gazette, September 17, 1880

We had proceeded but little further until I observed a lady dressed in black with a veil drawn over her face, standing by the side of the road. She was of most beautiful form. The head of the column passed her, when suddenly behind me I heard a piercing shriek, and on looking back saw her endeavoring to reach some one among the privates and crying most piteously, ‘oh! let me kiss my poor brother.’ But the soldier’s relentless bayonets crossed in front of her and remorsely put her back. The line of march was uninterrupted, and she followed her brother some distance crying and wringing her hands, but all to no purpose. She could not come near her brother who she knew was doomed to this living tomb.

We went on to the depot and there saw a large crowd of persons, but a certain Maj. Sherman who seemed to command for the time, had a wide circle established between us and them. There, young Allen again saw his mother, little brother, and also his step-father and many other friends. They gazed on him with sorrowful faces, but dared not reply by word or token to the many signs of affection made by him for fear of being arrested as sympathizers. The little brother could hardly restrain himself. He wanted to get at his brother. After we started I saw many carriages playing around with fair hands and snowy kerchiefs waving from the windows. Allen told me who they were. A friend of the Lt. Col. Who was along tried every means to convey some money to a Lt. Colonel, but it was no go. He got some afterwards however – no difference to the Yankees how. We got off just before night, and having stopped a few miles out of town, some beautiful girls came out to the cars, and there the vigilance of the guards was relaxed, for not only were they permitted to converse with Allen but to give him a sweet kiss all around. I think they were excusable; don’t you?

He pointed out to me his homestead with much emotion, and also many familiar and beloved scenes. Had it been me, I should have risked everything and jumped from the train. We started on to Louisville, Ky., where we arrived during the next day (28). Stayed one night in the city military prison. Found it cleanly. On the morning of the 29th we were off again. Just as we were starting however, a pretty, rebel sympathizer threw a couple of bundles of eatables into our crowd. There the officers and privates parted company, the former being destined for Johnson’s Island and the latter for Camp Douglas, Ill. We crossed the Ohio River in a steam ferry boat, landing in Jeffersonville, in Indianny (as the Yankees call it). There we took the train for Bellefontaine where we arrived before day on the 30th. About the middle of the forenoon we took the train again for Sandusky City, O., where we arrived in the afternoon, and the same evening were floated across the placid bosom of Lake Erie to Johnson’s Island to go from thence perhaps no more forever.

Oh! it is very hard to waste the prime of manhood there. But though without a precedent in civilized warfare I will not repine. A

few stations before we got to Sandusky, we passed the village of Clyde, where had recently been buried the mortal remains of the Yankee Maj. Gen. McPherson, who was killed about the time of my capture. He seemed to have been much beloved by all. While stopping here, little girls vending cakes and pies came around to the cars to trade with the Rebs. Having accumulated a small amount in greenbacks by selling out my tobacco to the Yankees, I concluded to invest, as I was sick and could not eat the rations of pickled pork issued to us raw. By permission of a guard I got on the platform and called to a little pie vender who came up, and while I was bargaining for a piece of pie, a sudden emotion of patriotism seemed to strike her, and snatching back her tray and giving me a scornful look, she backed off exclaiming as she backed, ‘you nasty stinkin’ old Reb! Nasty stinkin’ old Reb!’ And so I lost my pie. As appearances at the moment gave some just coloring to the charge I was not much disposed to find fault with her action except so far as my disappointment was concerned. – Major General James B. McPherson, commander of the Army of the Tennessee, was killed on July 22, 1864. Generals in Blue, pages 306 – 308.

A gentleman came around and in the kindest, most benevolent tones, conversed with us – I fancied, sympathizingly. While talking with us, the remarkable resemblance he bore to my old friend Dr. Jesse Wallace, of Holmesville, struck me forcibly, and the illusion was strengthened when some acquaintance addressed him as doctor. By reference to my short notes made at the time I find the following entries, except dates which seemed to have been a little confused.

July 31st – Found good friends from Summit who gave me clothes and a bank with one of them. 1st and 2nd – Quite sick, but wrote all the letters I was allowed. Feel the want of greenbacks. I will here remark that I felt the same need all the way, and even those of our party who had current money, were very niggardly with it. I raised a little by selling some tobacco that I had and by exchanging $20 in new issue that I had for eighty cents in greenbacks. From this time on until I come up to the present time, I shall not be able to keep up the correct dates of events, as I kept no record of events as they transpired. The night was dark and gloomy, when I with my party was ushered into the prison gates. Here it was amid surrounding gloom and strange weird scenes that I first heard that cry with which afterwards became so familiar to my ear, ‘fresh fish! fresh fish.’ Next week I will begin my prison life within the walls.

To Be Continued

The Magnolia Gazette, September 24, 1880

The acquaintances who found me were Captains J. H. Wilson and A.A. Boyd; Lieutenants Wilson and Louden (the latter I had not before known) of Summit; Lieutenants Gatlin, Sandell, Magee and White, of Pike County. They vied with each other in showing me kindness. I am particularly indebted to Capts. Boyd and Wilson, and Lieuts. Wilson, Louden and Gatlin. Lieut. Louden received me into his bunk with him and I have been enabled since that time, in some measure, to return the favors shown by him. He also took me into his mess – five of them – all of whom I found clever, young men, and all from Alabama but him. – “Lieutenant Wilson” is most likely 1st Lieutenant Joseph B. Wilson of the “Dixie Guards,” Company H, 39th Mississippi Infantry. He was captured July 9, 1863, at Port Hudson, Louisiana, and sent to Johnson’s Island prisoner of war camp. He was released after taking the oath of allegiance to the United States on June 11, 1865. – Compiled Service Record of Joseph B. Wilson, 39th Mississippi Infantry.

– “Lieutenant White” is probably 2nd Lieutenant John J. White of the “Dixie Guards,” Company H, 39th Mississippi Infantry. He was captured at Port Hudson, Louisiana, on July 9, 1863, and sent to Johnson’s Island prisoner of war camp. He was released after taking the oath of allegiance to the United States on June 11, 1865. – Compiled Service Record of John J. White, 39th Mississippi Infantry.

– “Lieutenant Magee” is probably 3rd Lieutenant William W.J. Magee of the “Monroe Quin Guards,” Company K, 39th Mississippi Infantry. He was captured at Port Hudson, Louisiana, on July 9, 1863, and sent to Johnson’s Island prisoner of war camp. Transferred to Point Lookout, Maryland, prisoner of war camp on March 21, 1865. Sent to Fort Delaware, Delaware, prisoner of war camp and released from there on June 12, 1865, after taking the Oath of Allegiance to the United States. – Compiled Service Record of William W.J. Magee, 39th Mississippi Infantry.

– Lieutenant Lorden” is probably 2nd Lieutenant Andrew Lowden, who served in the “Summit Rifles,” Company A, 16th Mississippi Infantry. He was wounded in action and captured at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 3, 1863. Lowden was sent to Johnson’s Island prisoner of war camp, then transferred to Point Lookout, Maryland, prisoner of war camp for exchange on March 21, 1865. Something must have delayed his exchange, however, as he was transferred to Fort Delaware, Delaware, prisoner of war camp, where he was released on June 12, 1865, after taking the oath of allegiance to the United States. – Compiled Service Record of Andrew Lowden, 16th Mississippi Infantry.

The prisoners were all that time allotted by blocks and messes. I was assigned to Block 1, Mess 11. Since that time we have also been divided into companies. Mine is company 22. The block indicates the building we stay in; the mess, those who draw rations together, and the company is composed of those whose names are on the same roll, and who answer at the same roll call. The blocks are long, two-story frame buildings, arranged on two sides of a broad street, running north and south. There are thirteen of them, the last being in the middle of the street at the north end. The southern blocks are cut up into small rooms and well sealed but the others are in large, open sealed rooms, more comfortable in warm weather, but terrible in cold weather. I could not get into a sealed block, and indeed, did not at first know the relative advantages. The cooking was at that time done in small end rooms below stairs, men being detailed or hired by the messes to do the cooking for the whole mess – those who were able paying extra for any extra cooking they had done. Now, separate blocks have been erected in the rear of the occupied blocks, especially for cooking and eating.

When I first came in, sutlers were in operation who supplied moneyed men with all they wanted to eat, but that privilege has been cut off, and the only extra supplies now received are on the surgeon’s certificate of a necessity therefore, and this only from near relatives. The government ration issued is little more than half enough to satisfy the appetite, and the consequence is that much suffering is entailed upon us all. But at present writing, and for some days past the ration has been better measure, and we have not been suffering so much.

Mail Arrangements &c.

At the time of my arrival on the Island prisoners were permitted to write one letter per day, of one page of ordinary letter paper each, but that was soon changed so as to allow them to write but two letters per week. All letters are sent off unsealed, and are read under orders of a superintendent of prison correspondence, to see that they are not too long, and that they contain nothing contraband. As many letters as come to the office may be received provided they conform to the above regulation as to matter and length. Mondays and Thursdays are the mail days. Each person prepares his letter and deposits it in a box kept in each room for that purpose. Every room has its mail carrier, who carries the letters to the office, generally, on the previous evening. After the mail comes into the prison in the morning, this carrier attends the office and gets the mail matter for his block or mess as the case may be. Prisoners are permitted to take as many newspapers as they see proper.

Details &c

Each room has its regular detail of two men each day, whose daily duty it is to bring water and the wood for the use of the room during the day, and to sweep the room, at least, twice during the day. In addition to this detail some rooms have a special detail to bring water for cooking purposes, for although there are cooking stoves in the kitchen, yet, nearly every one does more or less cooking in the dwelling apartment. There is also a daily police detailed for cleaning around the blocks and kitchens, emptying slops in the dredging carts, &c. Sometimes when ditching is to be done, sinks dug or removed, or any other extra work, a special police from a mess at a time is detailed for that purpose, all taking their regular turns – the general and the lieutenant being found side by side, spade in hand. Details are made daily from the prison to serve in the hospital. In addition to this the Young Men’s Christian Association furnished their daily detail. The Masons also make a detail to attend to their own, and the Mississippians – perhaps other states – have organizations to relieve the destitute from their particular state. Each mess and company for police and room has its chief, who regulates and directs the operations of their mess, police or room. Thus it will be seen that we have a little government of our own which works with a good deal of harmony.

Correspondence

The prisoner of war thinks a great deal of his correspondence, and well he may, for it is through that medium alone that he is enabled to receive any comforts other than the prison fare which is meager enough. It is always a sort of festival occasion among the prisoners from any particular locality when any one of their number receives a letter from home. Many of us have friends in the North who write to us and do us many favors. During the early days of my incarceration I wrote to some of my wife’s relations who responded promptly and substantially. I wrote to one of her uncles who I afterward learned had been dead for some time, but three others immediately answered my letter, two of whom sent me money, and one tendered his services to me in any manner that he could serve me. He has since that time nobly redeemed his promise, and is still laboring for my good. I have preserved all their letters which I trust may yet be perused by loving eyes far off from here.

Note: Before passing to my next caption to-wit, “Amusements,” I will examine my old correspondence and if I can find any thing that would seem interesting to the general reader, I will give it in my next, with explanatory remarks that I desire to make.

To Be Continued

The Magnolia Gazette, October 1, 1880

It sometime happens to the tempest ridden mariner, that he can see in the dim as he tosses restlessly from the wide expanse of water’s distance, a long skirt of cloud, in reality, embedded up on the surface of the water, and his imagination the wide expanse of water’s distance, a long skirt of cloud, in reality, embedded upon the surface of the water, and his imagination, leaping and bounding from craggy boulder to sea-beat shore, from shore to fertile valley, from valley to vine-clad hill, from hill to flowery meadow, converts it into a Paradise, more beautiful and glorious than perhaps has any actual existence on earth. And the mariners together gaze upon the illusory appearance and talk about it. Each gives his own ideas of the beauties he imagines have there an existence. If one is an adventurer seeking to unearth the golden sands that mother earth has locked in her secret embrace, he revels in the bright treasure that he imagines lie hidden there. If he is a visionary, a dreamer or a lover, his imagination revels in an untold wealth of beauty, loveliness and verdure; and if thirst is consuming, or hunger gnawing at his vitals, his imagination pictures the ice-cold, silvery, sparkling rivulet, leaping from the mountain’s brow to the deep tangled shaded glen, thence bounding from crag to crag, and trailing in a silver thread across the beautiful meadow below until it mingles into an undistinguishable body with old ocean’s waves; and anon he imagines that “sea girt isle” to be the abode of some ancient, lordly line, perhaps of kings whose tables are groaning with all the rich vivands that could tempt the appetite, or minister to the taste of the most fastidious gourmand.

Thus was it ever with us in prison. While there existed a thousand exterior circumstances, which it is but natural to suppose would engage most of the attention of the prisoners of war, yet the average man is so constituted that when we came together at twilight hour, our conversation would generally drift in the direction of the culinary. On such occasions many were the pictures drawn of good dishes, until our bowels would yearn for the flesh pots, and our very natures would loath the prison stuff with which our existence was prolonged. Often have I been reminded on such occasions of the anecdote of the two old darkies, who made a bet that each one could, on the first trial, name a better grub than the other, another old darkie supposed to be a complete judge in such matters being made umpire. When they had drawn straws to see who should have the first say, the one who won it scratched his pate for a moment and then said: “I tell you niggers, gub me good fat possum roasted brown, befo’ de fish, wid ash-cake givered wid corn corn shucks, rolled in de hot ashes twell hit is jist dun, den farewell world, dis nigger wants no mo’. Now Jake, you say!” Jake lifted his grief-stricken face and with sorrow in his tones said: “G’way, g’way nigger! You’s dun gone an’ telled it all an’ lef nuffin at all fur dis nigger to tell.”

Now, the reader, if he or she, has been patient enough to read this far, will be pretty apt to inquire what all this has to do with what I promised, to-wit, a few extracts from my old correspondence. It is this: While we were shut up on Johnson’s Island, the burden of our theme generally, in our letters was, something to eat, or that which would bring it. The unlooked for friends and favors that penetrated in one form or another to my prison cell, touches me very deeply.

Among the earliest communications received was one from a lady whom I had never heard of before, but whom my heart has had cause a thousand times to bless, and to whom the Mississippi prisoners should rear a pillar of marble commemorative of her noble deeds to them. I do not know where she is now, but if this should ever meet her eye or that of any of her friends, I hope they will forgive the publicity thus given to her name, which is already dear to a thousand soldier’s hearts.

Dear Sir – Your letters to friends in Monticello and Holmesville I have forwarded. I took the liberty of reading them. Seeing you are in want of one thing that is very necessary to a person’s comfort these days, I forward you by Adams Express, twenty-five dollars, and if you will write to Mrs. Mary Warner, 1227 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, for clothing, and send your size, she will send it to you. I urge you not to hesitate in doing this. Mrs. W. has $100 which I sent her last week for my dear boy, who was seriously wounded (on the 28th of July near Atlanta) and it was supposed he was a prisoner. As no intelligence comes from him through the Federal lines, I have almost given up in despair of ever hearing more of him (which has nearly crushed me), and if living, it is more than he needs for his present use. When you receive remittances from your home you can return it to Mrs. W., or you can consider it a loan, payable to me when sweet peace returns to bless us once more. Therefore, do not hesitate in accepting it as I have a great sympathy for prisoners; and if it was in my power to relieve all their wants, no sacrifice would I consider too great.

Please writer, give me your rank, the company and regiment, as I have many correspondents in Hood’s army. My poor boy belonged to the 10th Regiment, Tucker’s Brigade. Praying that you will not have to spend the winter in that cold and bleak Island, but will be permitted to return to friends and ‘home sweet home.’I subscribe my self if truly, a prisoner’s friend.

Mrs. George W. Baynard

‘Way Side,’ near Natchez

August 29th 1864

The above letter was directed to me at ‘Block 11, Mess 1, Johnson’s Island.’ I did not again receive a letter from the ‘prisoner’s friend’ until as she said in the former one ‘sweet peace’ had returned to bless us once more. The next was in reply to one from me and was dated ‘Way Side, July 25th 1865.’

Your letter has just come to hand and I hasten to reply, to tell you how I rejoice with you to hear that you are free; that you are

once more permitted to be with loving ones at home. Ah! Well can I imagine the joy of a mother, of a wife, to welcome home the returning soldier, and how endeared they are after the suffering and hardships they have endured. It seems so hard that the true defenders of our land were not rewarded; that Southern patriotism, that Southern valor, was all in vain – our country, our fortunes lost!

The Yankees may change our acts, govern our tongues, enslave our bodies but our hearts they never can reach. Our spirits will be Southern still, and scorn we shall ever feel for their narrow, cold-contracted natures. Our hearts will be Southern hearts forever, and we shall ever be proud of the blood that makes our love warmer, our acts nobler than theirs could ever be.

Tis so sad to see the sweet Sunny South, our once happy land reduced to poverty, and then ‘tis so beautiful to see our noble boys and girls who have been reared in every luxury and extravagance, not at all despairing, but cheerfully go to work to maintain aged fathers and mothers. My husband and I feel that hired labor will not pay. When we contrast our situation with others less highly favored, we find we have more cause for gratitude than repining.

We have the satisfaction of knowing that it (cotton sold for Confederate money) added greatly to the comfort of our needy soldiers, though my husband was bitterly opposed to secession, yet, he was true to his country and her defenders. Our home was the soldier’s home. ‘Tis such a pleasure to feel we did our duty; but to think our noble boy was sacrificed so uselessly – his head lying in a cold, unknown grave. Ah! the crushing weight of agony our hearts have endured. Life can never be to us what it would have been to him. He was so well calculated as a prop to lean on in our old days. But he fell in a glorious cause, and better for him to have fallen than to have shirked from his duty. I try to be resigned to God’s will, as he knows what is best for us. But I must stop this _____ and hurry on.

I am particularly interested in my correspondents made during their imprisonment. The little you said of your future prospects interested me and I sincerely hope that God in his goodness has many bright days of happiness and prosperity in store for you. Even though the future looks dark and joyless to us, we should trust in God. He judges not as man judges, and will not forsake us in the night time of sorrow and care if we love and serve him.

I received a letter a few days ago from our mutual friend Mrs. Warner. She wrote so affectionately of her nephews, and said: ‘Among them all there was none she was more pleased with than Capt. —– (delicacy forbids me to give the name thus complemented.)

You acknowledged the receipt of the first remittance forwarded you, the second $25 which was sent in January, you did not, and I often wondered why; as I wrote several times to you and no answer came. The mystery is solved now as I see you did not receive it, which I regret is not the only remittance I sent which was retained by some Yankee.

Sincerely your friend,

M. Jane Baynard

I received another letter from the above noble lady dated Sept. 26th, ’65, but as it treats mostly of business I will not make any extracts from it. Interesting extracts will form the body of my next. – Mary J. Baynard was the wife of George W. Baynard of Natchez. On the 1860 U.S. Census for Adams County, George W. Baynard listed his occupation as “farmer,” and gave the value of his real estate at $16,000, and his personal estate at $28,000. Among the Baynard children listed on the census was 17 year old Daniel F. Baynard. He enlisted in the “Natchez Southrons,” Company B, 10th Mississippi Infantry, on March 8, 1862. Daniel was wounded and captured at Atlanta, Georgia, on July 28, 1864. Sent to the 1st Division, 15th Army Corps Hospital, he was listed as having wounds to the pelvis and left ulna. The hospital record simply says of Daniel, “died.” – Compiled Service Record of Daniel F. Baynard, 10th Mississippi Infantry.

To Be Continued.

Magnolia Gazette, October 15, 1880

Sometime after I had been in prison the following note was placed in my hands, which was quite consoling to me, because it gave me assurance that in my exile I was not quite forgotten by my friends at home. Col. Nixon was also in prison. He was, I think, connected with the New Orleans press.

Summit, Miss., Sept. 12, 1864

Col. J.O. Nixon, Johnson’s Island

Dear Colonel – I have just learnt that Capt. John S. Lamkin, a personal friend of mine, who was captured near Atlanta, is now on Johnson’s Island. He is, no doubt, without means, and I write to solicit your kind offices for him. He and his friends have ample means(?) but have no means of getting them to him. If you can aid him, the money will be promptly refunded when possible, and your kindness will be duly appreciated by Capt. Lamkin and esteemed a personal favor by most truly, your friend.

W.H. Garland

– James Oscar Nixon was owner of the New Orleans Daily Crescent newspaper, and during the war was Lieutenant Colonel of the 1st Louisiana Cavalry. Captured in Kentucky in July 1863, he was sent to Johnson’s Island, Ohio, prisoner of war camp. He was paroled on December 19, 1864, and given the privilege of going at large in the North, though he was required to report in writing monthly to Brigadier General Henry W. Wessells. – Records of Louisiana Confederate Soldiers, Volume 3, Book 1, page 1287, compiled by Andrew B. Booth.

I received another letter dated at Milan, O., Oct. 6th, ’64, directed to me as ‘Prisoner of War, Johnson’s Island,’ which threw me into a high dudgeon. I had never seen or heard of the lady who wrote it, and until I began to ‘smell a very large mice,’ I thought she was volunteering advice, or assuming a prerogative which was in no way becoming. To my subsequent regret, I replied in a manner corresponding with my construction of the language used, which I construed literally. I was yet to learn that correspondents of prisoners were under the strictest military surveillance, and if any one manifested too strong a sympathy with rebel prisoners, he or she was subject to be dealt with. Then I learned that she was simply ‘throwing dust’ in the eyes of the prison authorities, while she was really desirous of doing me a kindness. She knew that every letter coming in to the prison had to be read by the superintendent of prison correspondence, as before stated, and by that letter she would establish her loyalty, and her right to address me; for she showed a sort of relationship, and no one but relatives were allowed to correspond with prisoners. Mrs. Warner, who was mentioned in a former issue must have had a hundred nephews in the prison – par parenthese.

I will remark that Mrs. Warner mortgaged her estates to raise funds to aid Confederate prisoners, which so crippled her that she could never recover, and her homestead being about to be sold to meet the obligations of the mortgage, her war nephews have inaugurated a movement which, is now going on to raise the mortgage and relieve her home. Extracts from the letters to which I allude, are as follows:

The letter you wrote to Dr. Kennicott (my wife’s uncle) of Chicago, has been sent me for answering, for reasons which I will state: Your wife’s uncles, Dr. William and John, both died over a year ago. Wm’s daughter was visiting my step-mother, Mrs. B.E. McMillan, of Buffalo. She thinking she could not communicate with you, sent me the letters (my father was a cousin of the Dr.). She wished me to direct you to write to your wife’s cousin, William Welch, of Gowanda, N.Y., and make your wishes and wants known.

The following was the part I kicked at:

I will only add that you may be thankful every day, your lot fell to Johnson’s Island. I am acquainted with many of the officers and men, and know what your fare is. We have just heard of the death of a friend, Capt. C.H. Riggs, a prisoner in Macon, who might have lived, had he fared as well as those where you are. Write if you receive this and I will try and forget that we are enemies, and do as I hope mine may be done by. Yours truly,

Mrs. Eugenie Penfield

Milan, Ohio, Erie Co.

I did write: not only to her, but to those she mentioned, who all nobly responded to all my necessities. The following is her reply, dated Milan, Jan. 1st, 1865:

Your favor by your friend received. I have not forgotten you if I have been negligent. I wish you a happy new year (as is possible under the circumstances) and may you live to see many a happier one. Mrs. Wells Brooks and daughter are with me for a short time, and if you can tell us any news of her brother, G.S. McMillan, you can confer a great favor. There was a letter received from him over a year ago. His mother died last March. Mrs. Brooks buried her eldest daughter a year ago now. I have been trying to send you a cask of cider and a barrel of apples, but the prairie has been almost impassible this fall. The cider is too old now, but apples you shall have as soon as possible, provided you will be allowed to receive them. When did you hear from your family or Mr. Tennisson, and how and where are they? I should like to hear from you soon. I remain, yours truly,

Mrs. Eugenie Penfield

Milan, Erie Co., Ohio

I did not seem to get the apples. The authorities would not let me have them. Next week I will resume the regular course of my recollections as written in prison. I have many other letters but the foregoing will suffice.

– In the 1860 U.S. Census for Erie County, Ohio, James J. Penfield, age 34, and his wife, Eugenie, age 26, were living in Milan Township. James was a lawyer, and listed the value of his real estate holdings at $1,200, and his personal estate at $600.00. Both James and Eugenie were apparently both Unionist in sentiment. in 1860 James was chairman of the committee that chose delegates to the statewide Republican convention. (Sandusky Register, July 17, 1860). On June 11, 1861, the Sandusky Register printed the following thanks from the men of Company K, 23rd Ohio Infantry: “Also to Mrs. Eugenia Penfield for nice rosettes, which were presented by her to our company. They will be preserved with care. E. Weller”. Why Eugenie Penfield chose to aid Confederate prisoners is a mystery; perhaps she could not stand to see any human being suffer, regardless of their political beliefs.

To Be Continued

Magnolia Gazette, October 22, 1880