On January 9, 1861, the Mississippi secession convention voted to leave the Union, making it the second southern state to secede. The dramatic scene at Mississippi’s capitol building was witnessed by hundreds of well-wishers, and included in the crowd was the nationally known entertainer Harry McCarthy, billed as “The Man of Many Parts.” What McCarthy witnessed at the secession convention inspired him to write one of the great songs of the Civil War, a ballad that would be sung by thousands of Southern voices during the course of the conflict; “The Bonnie Blue Flag.”

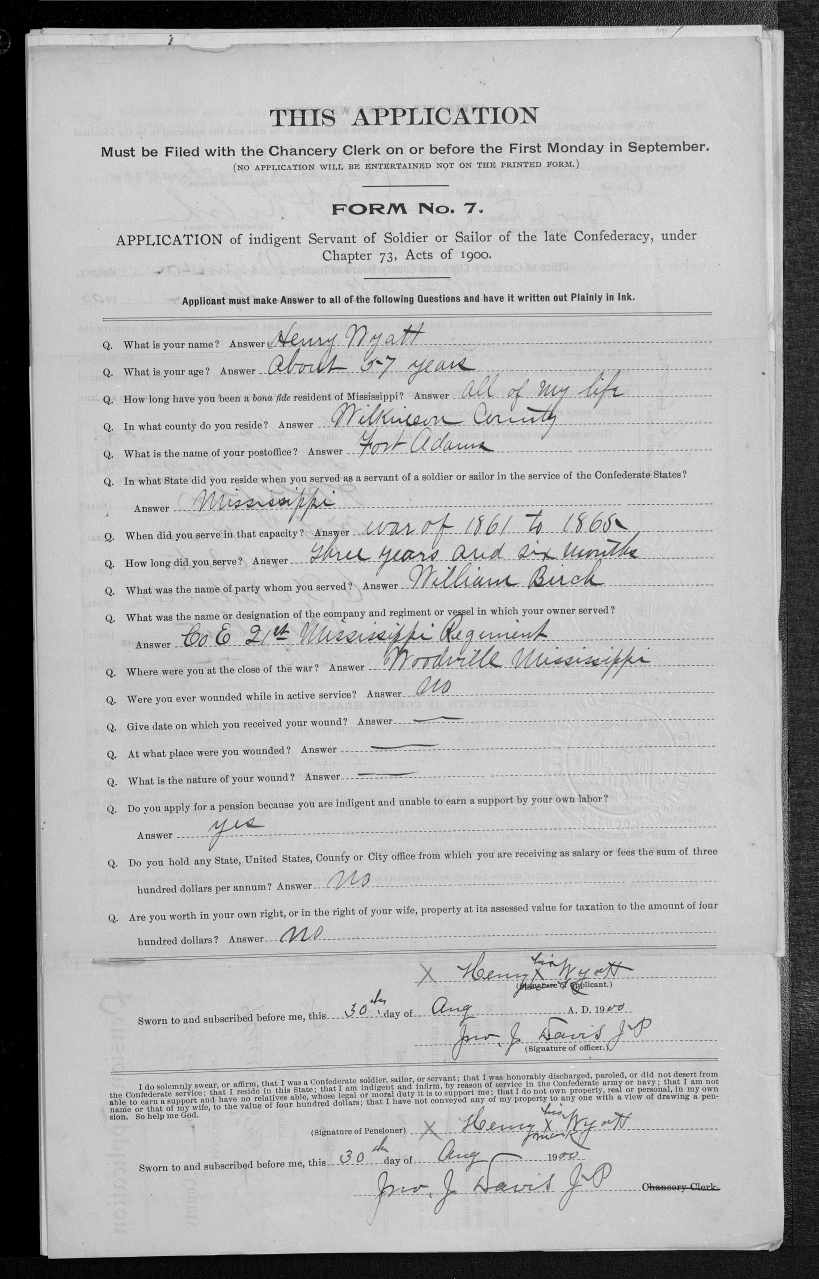

John Logan Power was a printer living in Jackson in 1861, and he was at the state house reporting on the meeting for one of the local newspapers. Many years later he wrote an account of what he saw during the convention:

“It so happened that I reported the proceedings of the convention for the Mississippian; was admitted, by special resolution, to the secret sessions, and my report was so full, and regarded as so accurate, that the convention ordered five hundred copies printed in pamphlet form…At this point, Mr. C.R. Dickson entered the hall, bearing a beautiful silk banner, with a single star in the center, which he handed to the President of the convention, (Hon. Wm. S. Barry, of Lowndes,) as a present from Mrs. H.H. Smythe, of Jackson. The President remarked that it was the first banner unfurled in the young Republic, when the members saluted it by rising – the vast audience uniting in a shout of applause.”

Power went on to explain how the song ‘The Bonnie Blue Flag’ came to be written:

“I was a deeply interested spectator of all this, having a seat at the secretary’s desk, and in my ‘Recollections’ of the occasion, occurs this paragraph: ‘It may be interesting here to note that the popular war song, “The Bonny Blue Flag, That Bears a Single Star,’ was the product of this episode. Harry McCarthy, a comic actor, was then holding forth in the old theatre near Spengler’s corner, on Capitol Street. He wrote the song immediately after the scene at the Capitol, your speaker put it in type from his manuscript – the ink being scarcely dry on the paper – and that night it was sung, for the first time, by its author.’

(The Clarion-Ledger, Jackson, Mississippi, February 7, 1895)

The first time Harry McCarthy performed “The Bonnie Blue Flag,” he knew he had a hit on his hands by the audience reaction to his new tune. In 1879, a correspondent identified only as “C.E.M.” wrote an account of the first time that patriotic air was sung in front of a live audience:

During the last few days of the Convention, Harry McCarthy, supported by a young lady,

who accompanied him in his original and selected songs, was giving a variety of entertainments at Spengler’s Hall, in that city, consisting of songs, serious and comic, dancing, instrumental music, &c. On the afternoon of the 9th of January, Judge Wiley P. Harris, one of the soundest lawyers living, met the gifted young Irishman on the street, and remarked: ‘Mac, the Convention will adopt the ordinance of secession sometime this afternoon, and you will have a large audience this evening. Permit me to offer a suggestion: Why can you not compose a song pertinent to the occasion? Give us a patriotic song – one which shall, perhaps, be universally received as a national air – something soul-stirring and patriotic, that may become as immortal as the ordinance itself.’ Young McCarthy caught the idea at once, retired to his room, and in three or four hours was singing, for the first time in public, the ‘Bonnie Blue Flag,’ to a house crowded to its utmost capacity. And not once, or twice, or thrice only, did he sing the new song that night; but he was encored again and again, twelve or fifteen times at least, until he became hoarse from singing and the audience almost exhausted from applauding. The scene was one which, literally, must have been seen to have been appreciated…From that hour there was nothing but the Bonnie Blue Flag in Southern air. As the visitors to Jackson returned home – north, east, south and west – they spread it everywhere. (The Comet, Jackson, Mississippi, December 20, 1879)

After leaving Jackson, Harry McCarthy made his way to New Orleans, where he met with the firm of A.E. Blackmar and Brother, one of the largest music publishing houses in the south. Blackmar bought the rights to “The Bonnie Blue Flag” for $500 and a piano, and soon was selling beautifully decorated sheet music of the tune. (“Musicman of the Confederacy,” by Lawrence Abel. Civil War Times, Volume XLIII, Number 3, page 50, August 2004)

The lyrics of “The Bonnie Blue Flag” are as follows:

We are a band of brothers, and native to the soil,

Fighting for the property We gain’d by honest toil;

And when our rights were threaten’d, The cry rose near and far,

Hurrah for the Bonnie Blue Flag, that bears a Single Star!

Hurrah! Hurrah! for Southern Rights Hurrah!

Hurrah for the Bonnie Blue Flag, that bears a Single Star!

As long as the Union was faithful to her trust,

Like friends and like brothers, kind were we and just;

But now, when Northern treachery attempts our rights to mar,

We hoist on high the Bonnie Blue Flag, that bears a Single Star.

Hurrah! Hurrah! for Southern Rights Hurrah!

Hurrah for the Bonnie Blue Flag, that bears a Single Star!

First, gallant South Carolina nobly made the stand;

Then came Alabama, who took her by the hand;

Next, quickly Mississippi, Georgia and Florida,

All rais’d on high the Bonnie Blue Flag that bears a Single Star.

Chorus: Hurrah!

Ye men of valor, gather round the Banner of the Right,

Texas and fair Louisiana join us in the fight;

Davis, our loved President, and Stephens, Statesman rare,

Now rally round the Bonnie Blue Flag that bears a Single Star.

Chorus: Hurrah!

And here’s to brave Virginia! the old Dominion State

With the young Confederacy at length has link’d her fate;

Impell’d by her example, now other States prepare

To hoist on high the Bonnie Blue Flag that bears a Single Star.

Chorus: Hurrah!

Then here’s to our Confederacy, strong we are and brave,

Like patriots of old, we’ll fight our heritage to save;

And rather than submit to shame, to die we would prefer,

So cheer for the Bonnie Blue Flag that bears the Single Star.

Chorus: Hurrah!

Then cheer, boys, cheer, raise the joyous shout,

For Arkansas and North Carolina now have both gone out;

And let another rousing cheer for Tennessee be given –

The Single Star of the Bonnie Blue Flag has grown to be Eleven.

Chorus:

Hurrah! Hurrah! for Southern Rights; hurrah!

Hurrah! for the Bonnie Blue Flag has gain’d th’ Eleventh Star!

(Macarthy, Harry. TheBonnie blue flag. Oliver Ditson & Co., Boston, 1890. Notated Music. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200002434/>.)

Although he wrote many other patriotic tunes during the Civil War, “The Bonnie Blue Flag” was his biggest hit, and it is the one that he is remembered for today. The account of how Harry McCarthy came to write the song is well known, and has been published many times over the years; however, I believe there is a little more to the story that has never been told. I believe Harry McCarthy’s inspiration for “The Bonnie Blue Flag” was a song he had either heard or read about in Vicksburg Mississippi several weeks before the state secession convention met.

In early December 1860, Vicksburg’s citizens were swept up in the furor following the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency of the United States. Secession and war were the topics on everyone’s lips, and Vicksburg’s young men, like those all across the south, were preparing for a fight. The city had a number of militia units, including one named the Vicksburg Sharpshooters. On May 9, 1861, a local newspaper noted:

The Citizen Office has made an humble contribution to the brave Vicksburg Sharpshooters, by presenting each member with a beautiful blue badge, bearing the code [coat] of arms of the State of Mississippi, and the mottoes, ‘Southern Rights,’ ‘For this we Fight.’

It was a good time to be a performer in Vicksburg, as the excitement over the current political situation made the locals eager to see patriotic entertainments. On December 11, 1860, Harry McCarthy gave his first performance in Vicksburg, and it was very well received. The next day one local citizen that attended the performance gave McCarthy and his group a very strong endorsement:

I was present at McCarthy’s Entertainment last evening, and can freely say that I have seldom, if ever, been more amused and attracted. His personations are to the life, in whatever character he represents. Dutch, Irish, Yankee or negro, his songs are inimitable, and his style, in all his efforts, impressive and unique; he stands alone and wholly unrivalled in his line…This is truly Southern entertainment, Mr. McCarthy being a citizen of Arkansas, and the Legislature of that state has given him a free license to exhibit anywhere within her borders and he comes to us, unlike most men in his line, well and highly recommended. Advise all your readers to go and hear McCarthy if they would enjoy an hour devoted to mirth and good feeling.

C.H.

(Daily Evening Citizen, December 12, 1860)

Harry McCarthy performed in Vicksburg until December 13, having his last concert that night. The newspaper article about the performance noted:

Last night this gentleman performed to a small, but highly respectable audience. His Lament of the Irish Emigrant, was the best we ever heard, and we must say if Harry ever makes his mark, (which we consider he has done,) it will be with that song. Miss Fanny Pierson, who assisted him, did it well. Harry informs us that he will pay us another visit in a short time; his engagements are due at other places and he must fulfill them. When he returns let him have a rousing house.

(Daily Evening Citizen, December 14, 1860)

Vicksburg’s citizens loved a good show, but one thing they most decidedly did not like performers that held sympathies for the North. On December 14 the Evening Citizen noted that such a group was in the city:

SHOWS – The hard times are too tight upon our citizens now to allow them to spend much money in attending the performances of traveling minstrels. Even when a well known and popular troupe comes along this way, it is a hard matter to get a good house in these pinching times. But when a company that borrows part of its name from a Northern city, and whose political sympathies are suspected by many as being of too equivocal a character to receive much encouragement from a Southern community comes along, we think it is no more than justice for our citizens to look around and see who they are dealing with before they extend the hand of welcome to the company which intends to open tonight.

(Daily Evening Citizen, December 14, 1860)

The newspaper did not give the name of the group with the suspect sympathies, but four days later they did note that the Metropolitan Troupe of Minstrels played, and that “we have never seen a company play to a better house; the only drawback was that there were no people in it.” This may very well have been the group eluded to in the paper on December 14.

(Daily Evening Citizen, December 18, 1860)

Into the politically charged atmosphere of Vicksburg came another group, one with a national reputation; the Kneass Family, head by Nelson Kneass. Born in Philadelphia in 1823, Nelson Kneass made his first stage performance at the age of five. By 1860 he was touring the country with his wife and children who performed with him. Nelson Kneass was best known for his song “Ben Bolt,” first performed in 1848, which became a major hit in the United States and Europe.

The Kneass Family was known to perform patriotic Southern songs, and the Evening Citizen highly recommended the show to their readers:

It is with pleasure that we announce to our readers a real musical and artistical concert by

the talented Kneass Family, each one of whom has a thorough musical education – no clap trap such as bones or tamborines, are resorted to attract the public: pure music from the soul, is the attraction. Mr. Nelson Kneass, universally known in this country, as a composer and author of many beautiful songs and ballads, among which is the famed Ben Bolt, (that has run through twenty-seven editions), the Veteran, Miller Song, Aunty Brown, Deep in a Shady Dell, Only See my Jenny Spinning, and many others; also Mrs. N. Kneass, who has a superior Mezzo Soprano voice, and is unsurpassed in such songs as the Star Spangled Banner, Marsellaies Hymn, France I Adore Thee, &c. Then there is the singing bird of the South, Miss Annie, of sweet sixteen, who is the centre of all attractions, in the melodius soprano voice; and lastly though not least is Master Charles with his stoical face, which in anything comic is funny indeed. We would here take occasion to inform the public, that we are to have some truly soul stirring patriotic Southern songs and ballads, composed by this talented family (and which has created great sensation everywhere they have been sung.) During their stay here which along should be enough to fill the Apollo Hall to overflowing, we predict that some of those songs will be the national songs of the Southern Republic of Columbia. We say to one and all go hear them.

(Daily Evening Citizen, December 18, 1860)

The Kneass Family had their first show in Vicksburg on December 19, 1860, and from the account of the show, it was very well received:

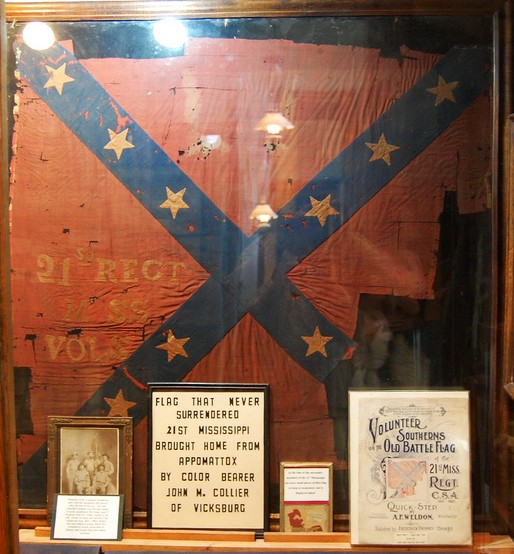

The celebrated Kneass Family commenced a series of entertainments last night at the above place, and the brilliant success which they achieved will insure them crowded houses for the remaining nights they stay. We cannot particularize upon their ‘bill of fare’ last night, but to our mind, there was more music in their song, ‘We Come from the Hills,’ than in any other they produced. The ‘Female Auctioneer,’ by Miss Annie, and the “Southern RIghts Song,’ by Mrs. Kneass, wee both most rapturously encored while the ‘Batchelor’s Advertisment,’ and ‘Yankee Doodle Played Out,’ kept the house in a perfect uproar. As this is emphatically a ‘Southern Institution’ of great talent, we sincerely hope that they may be well patronized. We quote a stanza from the song of ‘Don the Blue Badge,’ composed and sung by Mrs. Kneass:

Tis time to secede – our cause it is right,

In urging us on to keep foes from our shore,

We’ll stop not to think, now danger’s in sight.

But fight as our forefathers have fought before.

And God in his greatness, in whom we trust,

With terror will strike our foes to the dust,

CHORUS:

Then don the blue badge, our foes we’ll defy,

We’ll fight for our rights or for them we’ll die.

(The Evening Citizen, December 20, 1860)

It is the last song, “Don the Blue Badge,” which I believe was the inspiration for the “Bonnie Blue Flag.” Unfortunately the Evening Post did not print the complete lyrics to the song, and despite a diligent search, I have not been able to find them. However, on December 29, 1860, the “Evening Citizen” published an article entitled “The Conflict,” which stated the necessity for immediate Southern secession to protect the rights of the slave holding states.

The reason that “The Conflict” is of interest is because the author quoted from “Don the Blue Badge” in his article. In one part he says the following:

When everything that is dear on earth to a true-hearted Southerner is threatened to be taken away, he must be utterly demoralized, and have totally lost his caste, if he does not raise his voice and his hands in defence of his rights. And yet a submission on the part of the South could be regarded in no other light than as an act of contemptible cowardice. The question has resolved itself into a very simple one; it is to submit to wrong and opppression, or fight for our rights.

‘So long as the Union kept firm to her trust, like brothers, like friends, we were kind, we were just; But not treachery throws its dark pall o’er our sight, each man for himself, and God speed the right, Heed not fanatics, we’re strong and we’re brave, like patriots we’ll fight our birth-place to save.’

(The Evening Citizen, December 29, 1860)

This part of ‘Don the Blue Badge’ has stanzas very similar to ‘The Bonnie Blue Flag,’ and ‘The Conflict‘ included more lines from the song in its final paragraph:

South Carolina has already taken her departure, and the 20th day of December 1860, will, for all time to come, be remembered as the day on which was inaugurated the first step to a Southern Confederacy. Mississippi and Alabama will go out simultaneously on or about the 8th of January 1861. ‘Tis time to secede – our cause it is right, in urging us on to keep the foes from our shore, we’ll stop not to think, now danger’s in sight, but fight as our forefathers have fought before, and God in his greatness, in whom we trust, with terror will strike our foes to the dust. Then don the blue badge, our foes we’ll defy we’ll fight for our rights or for them we’ll die.

(The Evening Citizen, December 29, 1860)

The Kneass Family performed in Vicksburg through December 22, 1860, and the day before their final performance the newspaper wrote of the troupe:

Last night there was a good attendance at the above place to witness the excellent entertainment of the Kneass Family. We were sorry to see so few ladies present, as we are certain they would enjoy themselves hugely in listening to the ‘singing bird of the South.’ We can heartily recommend this family to the patronage of our citizens, not only because they possess talent of a high order, but also because of their truly Southern sentiment, and as we can vouch for their being ‘sound on the goose,’ we hope to see them rewarded as their merits deserve.’

(The Evening Citizen, December 21, 1860)

After the Kneass Family ended their stay in Vicksburg, Harry McCarthy was about to being his second tour of the “Hill City.” His latest set of engagments started on December 27, and continued through January 1, 1861. It was during this time that some of the lyrics to “Don the Blue Badge” were published in the Evening Citizen.

On January 1, 1861, just eight days before his rendezvous with destiny at the Mississippi statehouse, Harry McCarthy gave his last performance in Vicksburg. The Vicksburg paper urged its readership to see the show:

HARRY MACARTHY – To-night Mr. Maccarthy will give the last of his inimitable entertainments at Apollo Hall. We hope to see a full house to give him a grand farewell bumper. He has given our citizens a heap of fun, and to-night he presents a bill far ahead of anything he has yet produced. We understand he intends visiting Jackson from here, and we would advise our Jackson friends to be on the lookout for a rich treat when Harry comes.

(Daily Evening Citizen, January 1, 1861)

Given the sparse evidence available, its hard to say how much influence that ‘Don the Blue Badge‘ had on Harry McCarthy – I can’t even say to a certainty that he saw a performance by the Kneass Family or read any of the newspaper articles that contained stanzas from the song. What I have is simply circumstantial evidence; McCarthy performed at Apollo Hall, the same venue where the Kneass family played; he was in the Vicksburg area, if not Vicksburg itself, during their stay in the city, and copies of the Vicksburg newspaper would have been readily available. I hope in the future that additional evidence will come to light to offer more evidence on the creation of one of the most popular Southern songs of the Civil War – ‘The Bonnie Blue Flag.’