In the summer of 1890, Joseph Tribble, a carpenter living in Grenada, Mississippi, decided to make a trip to his boyhood home in Kansas. Having been gone for thirty years, Tribble probably felt that no one would remember him, but he couldn’t have been more wrong. Shortly after arriving, Joseph Tribble was recognized, and immediately arrested. He was charged with the murder of Alexander Kincaid – a crime which had taken place in September, 1861, and had its roots in the conflict known as “Bloody Kansas.”

In the 1850s the turmoil in the Kansas territory foreshadowed the coming Civil War. The conflict had its roots in the

Kansas-Nebraska Act, which was a measure proposed by Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas to organize the territories because he wanted to build a railroad linking Illinois with California. Douglas realized that for the act to pass, he would have to make concessions to the South if he was to obtain their support for the measure. Thus the act repealed the provision of the Missouri Compromise that prohibited slavery north of 36* 30′ in the Louisiana Purchase lands. In addition, both Kansas and Nebraska territories were thrown open for settlement, and the immigrants themselves would decide whether these lands would be slave or free – a concept known as popular sovereignty.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed by Congress in May 1854, and the law set off an immediate firestorm of protest. Abolitionists in the North denounced the act as a slave holder conspiracy to add additional slave states to the Union. In the South, the law was very popular, as it was seen as an opportunity to add Kansas as a new slave state north of the old 36* 30′ Missouri Compromise line. An unintended consequence of the law was that Kansas turned into a battleground as abolitionist and pro-slavery settlers flooded into the territory.

In his biography of Confederate guerrilla leader William Clarke Quantrill, writer Edward E. Leslie summed up very eloquently this not-quite-a-war going on in Kansas in the 1850s:

Just as in Northern Ireland and the Middle East in recent decades, it was a tit-for-tat war, a war of retribution and retaliation. It was characterized by fiery rhetoric, with talented and unscrupulous propagandists on both sides. ‘War to the knife, and knife to the hilt!’ one newspaper editor cried. It does not matter which side he was on; such

sentiments were echoed by both sides. – The Devil Knows How To Ride, page 6.

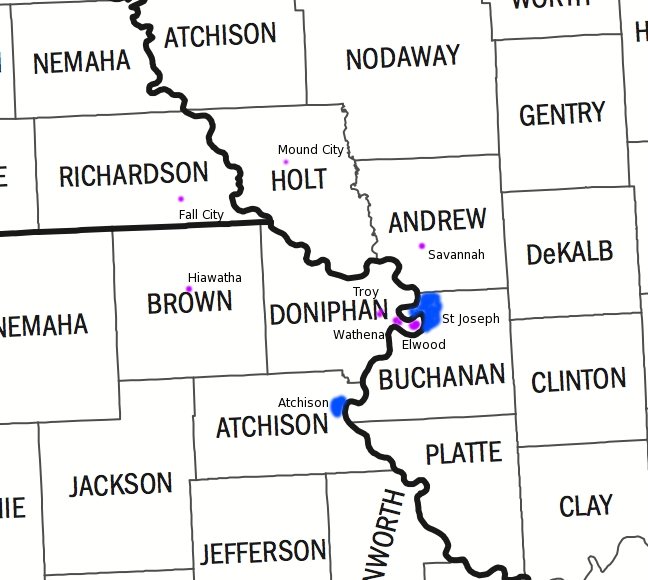

Joseph Tribble was born into this simmering cauldron of violence; I first found him on the 1850 United States Census as an 11 year old, living in Platte, Andrew County, Missouri, with his mother and his seven brothers and sisters. His mother, Cassandra, was a native of Tennessee, and all of the children were born in Missouri. Andrew County, located in the Northwestern part of Missouri and bordering on Kansas, was home to both pro-Union and pro-Confederate citizens during the Civil War, and was on the front lines of the guerrilla war during the conflict.

Sometime after 1850 the Tribble family picked up stakes and moved just across the state line to the town of Burr Oak, in Doniphan County, Kansas. There the family eked out a living as farmers; on the 1860 Census, Cassandra Tribble reported that she owned real estate worth $200.00, and had a personal estate valued at $100.00. Twenty-one year old Joseph was still living with his mother at this time, and listed his occupation as “farm hand.”

With the outbreak of war in 1861, citizens in Missouri and Kansas began taking sides and donning uniforms to fight. But in Missouri and Kansas, the war would not be confined to soldiers; civilians would be caught up in the ever expanding whirlwind of violence and terror. I don’t know much about Joseph Tribble’s life prior to the Civil War, but given subsequent events, it is safe to say that he was pro-Confederate in sentiment. Living in Kansas, he was bound to rub elbows with pro-Union men, and eventually one of these encounters turned violent. On September 19, 1861, the White Cloud Kansas Chief (White Cloud, Kansas), ran the following story:

A Union man named Kincaid, was murdered, on Sunday week, in Burr, Oak Township, by a Missouri Secessionist named Tribble. Kincaid was coming out of church, when Tribble stepped up to him, and asked him whether he was a coercionist? Kincaid replied in the affirmative, when Tribble stabbed him to the heart, then escaped over the river, with the assistance of Kansas traitors. The murderer is a brother to the ruffian whom the Pro-Slavery Democracy of this County attempted to shove into the office of County Treasurer, two years ago.

The murdered man was Alexander Kincaid, a small farmer who lived in Doniphan County. In the 1860 United States Census for Doniphan County, Kincaid listed his birthplace as New York, and he stated he had a personal estate worth $120.00. One interesting fact about Kincaid’s listing in the 1860 Census – he was on the same page as Joseph Tribble, meaning that they were neighbors. The two probably came into contact with each other quite often, and over time their political differences grew into an animosity that led to murder.

After killing Kincaid, Joseph Tribble did not wait around to face Kansas justice; where he went I have not been able to

discover, but he next appears as a private serving in Company A, 1st Missouri Cavalry. Enlisting in December 1861, Tribble’s service record gave the following synopsis of his wartime service:

Served in Missouri State Guard, engaged at Blue Mills, Lexington, Sugar Creek, Bentonville, Elk Horn, Farmington, Iuka, Corinth. Deserted May 1, 1863, returned February 1, 1864. New Hope Church, Latimore House, Kennesaw Mountain, Atlanta, Lovejoy. Transferred to Company I, September 12, 1864. Allatoona, Georgia, Franklin, Tennessee; deserted at Nashville December 6, 1864.

Joseph Tribble enlisted in the 1st Missouri Cavalry along with his brother Andrew. The older sibling was soon promoted to sergeant, but he was captured at the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern, Arkansas, and sent to a prisoner of war camp at Alton, Illinois. Apparently Andrew had seen enough of the war to suit him, as he took the oath of allegiance to the United States and was released from prison.

After deserting from the 1st Missouri Cavalry in December 1864, Joseph Tribble drops from sight until 1880, when he shows up on the United States Census in Grenada, Mississippi. The forty-one year old listed his occupation as carpenter, and he was living with his wife, Levisa J. Tribble, and their children, Claudia, Andrew, and Cassandra.

Joseph Tribble had spent a considerable amount of time in Mississippi during the war, and perhaps he liked what he saw of the state. He also had to know that with the war over and the Union victorious, returning to Kansas or Missouri would have entailed considerable risk for a man wanted for murder. By 1890, however, with 30 years between him and his crime, Tribble must have felt safe in taking a trip back to his old haunts in Kansas. But he could not have been more wrong. On July 6, 1890, the New York Herald ran the following story:

Murder Will Out.

Arrested for Killing A Man in Kansas Nearly Thirty Years Ago

St. Joseph, Mo., July 5, 1890 – Joseph Tribble, whose residence is on a plantation in the State of Mississippi, was arrested at an early hour this morning at Wathena, a little town just across the river from St. Joseph and in the state of Kansas. Tribble was a resident of Wathena twenty-nine years ago at a time when the border ruffians and bushwhackers run almost everything on the Kansas and Missouri sides of the river.

It was during these times in the year 1861 that Tribble, who sympathized with the Confederate cause, murdered Thomas Kincaid, who was a Northern sympathizer and who was at the time preparing to enlist in the Union Army. Immediately after the murder, on account of the feud then existing between Missourians and Kansans, Tribble made his escape, going to Mississippi, where he entered the Confederate army and served as a private until Lee’s surrender.

After the war he settled down on a Mississippi plantation, was married and now has in Mississippi a wife and three children, who have not yet been notified of the trouble he has gotten into. He had never visited his old home until the first day of the present month, when he came to St. Joe, then went to see friends in a little town ten miles north of here, and on the 4th he went to attend a celebration. He had no idea that any of his old acquaintances would recognize him, but they did, and his arrest followed. The murder was committed by a butcher knife in the month of September, 1861, and curious to say, the identical knife was found on his person when arrested. Tribble acknowledged that the knife was the one he used to murder Kincaid, and when asked why he carried it yet he answered: ‘I was coming back here on a visit the first time since the crime was committed and thought I would bring my friend of those times back with me.’ Tribble is now in jail at Troy, Kansas.

Justice moved quickly in the 1890s, and on July 16,1890, The Wichita Daily Eagle (Wichita, Kansas), reported on the opening of the trial:

The Tribble Trial

Troy, Kan., July 15 – The preliminary trial of Joseph Tribble, charged with the murder of Alexander Kincaid in September, 1861, is being held here today. A number of witnesses have been examined, but none have testified positively to the facts of the killing. Tribble is a resident of Mississippi and was here on a visit when he was recognized and arrested.

The Omaha Daily Bee (Omaha, Nebraska), also published an account of the trial on July 16, and their story includes more details about the murder:

Great was the excitement at Troy, Doniphan County, this state, today, the occasion being the preliminary examination of Joseph Tribble, who was arrested July 4 at Wathena for the murder of Alexander Kincaid on September 8, 1861. Tribble was rebel, Kincaid a man of union tendencies, although neither belonged to the regular armies. On the day mentioned, which was Sunday, the boys, both under twenty-one, met at a campmeeting. A quarrel ensued and they went at each other, Kincaid with a butcher knife, Tribble with a bowie knife. Kincaid was killed. Tribble went to Mississippi and did not reappear until July 4, when he was arrested. Today he was bound over in the sum of $7,000, which he is unable to give. The most intense excitement prevailed at Troy during the trial. The court room was crowded by men who had rebel tendencies and men of union proclivities and who openly stated them now. Tribble has a wife and five children in Mississippi, in destitute circumstances. He made no defense at the preliminary examination today.

One interesting statement was put forward in the Bee article – it noted that both Kincaid and Tribble were armed with knives – all of the previous statements about the murder made it sound as if Tribble simply stabbed an unarmed man to death. This information would turn out to have a great impact during the course of Tribble’s trial.

By early August, word of Joseph Tribble’s predicament had made its way back to Mississippi. On August 2, 1890, The Grenada Sentinel (Grenada, Mississippi), ran the following article:

Mr. Joe Tribble In Trouble

Arrested in Kansas for Killing a Man in 1861

Several weeks ago Mr. Joe Tribble of Jefferson, left here to visit relatives at Troy and other places in Kansas. While there he was arrested, charged with the killing of one Mr. Alexander Kincaid, in 1861. It seems that Mr. Kincaid was a rabid Federalist man, while Mr. Tribble was equally as strong a Confederate. They got into a dispute in which Mr. Kincaid was killed, and Tribble left the country and joined the Confederate Army. Mr. Tribble had a preliminary trial in Kansas some time since, and was bound over in the sum of $5,000, which bond he has not yet been able to give. None but state witnesses were examined and Mr. Tribble and his lawyers, as well as friends claim that they can easily prove that the killing was done purely in self-defense, when the trial comes before the Circuit Court. Some of his army comrades and other friends have been appealed to, and are now raising money to help him out of his trouble. We trust that all who can will contribute towards this end, and that Mr. Tribble will be acquitted. He made a brave Confederate soldier, and has a number of friends in this section. It will be hard for him to get full justice amongst strangers who know and care nothing for the South but to hate and malign her and her people.

The Grenada Sentinel article was very sympathetic to Tribble, but he was going to be tried by a Kansas jury, and his defense attorney would certainly have to work hard to obtain an acquittal for his client. The trial started in early October, 1890, and the Kansas City Times devoted considerable ink to the proceedings in the October 10, 1890, edition of the paper:

Joseph Tribble’s Hearing for a Murder in 1861 Opened at Troy

The case of Joseph Tribble for the murder of Alexander Kincaid in September, 1861, was called in the district court yesterday morning and the day was consumed in endeavoring to secure a jury. A special venire of twenty-six names was issued and this morning a jury was obtained and the trial begun. At 3 o’clock this afternoon the state rested its case and a short adjournment was had to enable the defense to prepare for its side.

One witness for the state testified that he stood by and saw Tribble stab Kincaid without any hostile demonstration on the part of the latter and that he repeated the blow in the back after Kincaid started to run. Also that before the first blow Kincaid had declined to fight Tribble. A lady testified that on the day of the murder she was visiting at a neighbor’s when Tribble came with bloody hands and upon being offered a basin of water to wash them, replied that he wanted the blood to remain so that when he reached Price’s army, he could show them the blood of an abolitionist.

After the killing Tribble went south with Price’s army, and had since made his residence in Mississippi, where he married and raised a family. Last Fourth of July he came back on a visit and was immediately arrested and placed in jail at Troy. Four witnesses who saw the killing, said that Kincaid had a sharpened butcher’s steel in his hand when he was stabbed by Tribble. By the few witnesses introduced by the defense up to adjournment it was proved that Kincaid had threatened Tribble’s life and the morning of the killing had sharpened the butcher’s steel for the purpose of killing Tribble. They met at the school house on Sunday, where church was held, and Kincaid struck Tribble and drew the steel. In self-defense Tribble drew a knife and struck the blow that caused death. The defense will set up the plea of self defense.

On this first day of the trial, the jurors had the difficult task of determining the truth from witnesses that told two entirely different stories of what happened 30 years earlier. If they believed one set of witnesses, Joseph Tribble had basically assassinated an unarmed, defenseless man. If you believed the other witnesses, Joseph Tribble had defended himself from a man who was intent on taking his life. Only time would tell which set of witnesses the jurors believed.

Today, a major murder trial might last for months; but in the 1890s justice was swift and sure, and on October 12, 1890, the Omaha World Herald (Omaha, Nebraska), announced the verdict in all caps:

A CASE OF SELF DEFENSE

Joseph Tribble was acquitted of a murder in Doniphan county, Kansas, today committed over thirty years ago. Tribble was a southern sympathizer and the man he killed was Alexander Kincaid, a recruiting officer for the Union army. The evidence conclusively showed that Tribble acted wholly in self defense. Tribble is a resident of Mississippi and was arrested here the 4th day of last July while on a visit to his relatives in this section.

Without having access to the transcripts of the trial, it’s hard to second guess the verdict of the jury. The thirty years between the killing and the trial must have worked in Tribble’s favor; memories fade over time, witnesses die or move away, and the animosities generated by the war had decades to subside. All of these factors probably had something to do with Tribble’s acquittal.

With his name cleared, Tribble returned home to Mississippi and the loving embrace of his wife and children. He had endured a difficult few months, but I have to think that the acquittal must have given him peace of mind; no longer would he have to look over his shoulder waiting for law to catch up with him. As the Reno Evening Gazette (Reno, Nevada), put it in their October 22, 1890 edition: “He has been 29 years in dread of the hangman’s noose.” Tribble would no longer have to worry about a death on the gallows, but I have to wonder if his conscience ever bothered him. Was he forced to relieve the killing in nightmares night after night? Unfortunately, the historical record is silent on the subject.

The last mention I can find of Joseph Tribble is in the Confederate Widow’s Pension application of his wife, Levisa. In 1916 the 71 year old woman applied for a pension in Hinds County, Mississippi, declaring that she owned no property and lived with her son. Levisa wrote that she and Joseph were married on March 3, 1867, and that he had died on July 10, 1898.