On this Memorial Day, I thought it entirely proper to write about the one Mississippian who devoted himself to preserving the records of the Magnolia State’s Civil War dead. The man in question was John Logan Power, an Irish immigrant who settled in Mississippi in 1856. When the war came, Power cast his lot with his adopted state, and served it very well throughout the entire war.

In February 1864, the Confederate Congress passed a piece of legislation with the

ponderous title of “An act to aid any State in communicating with and perfecting the records concerning its troops.” The purpose of this act was to create a new position for one officer in each state dedicated to collecting information on casualties to expedite the completion of “final statements of deceased soldiers,” so that their families could obtain any monies due them from the Confederate government. (Official Records, Serial 129, pages 189-190; available online at: http://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/129/0189.)

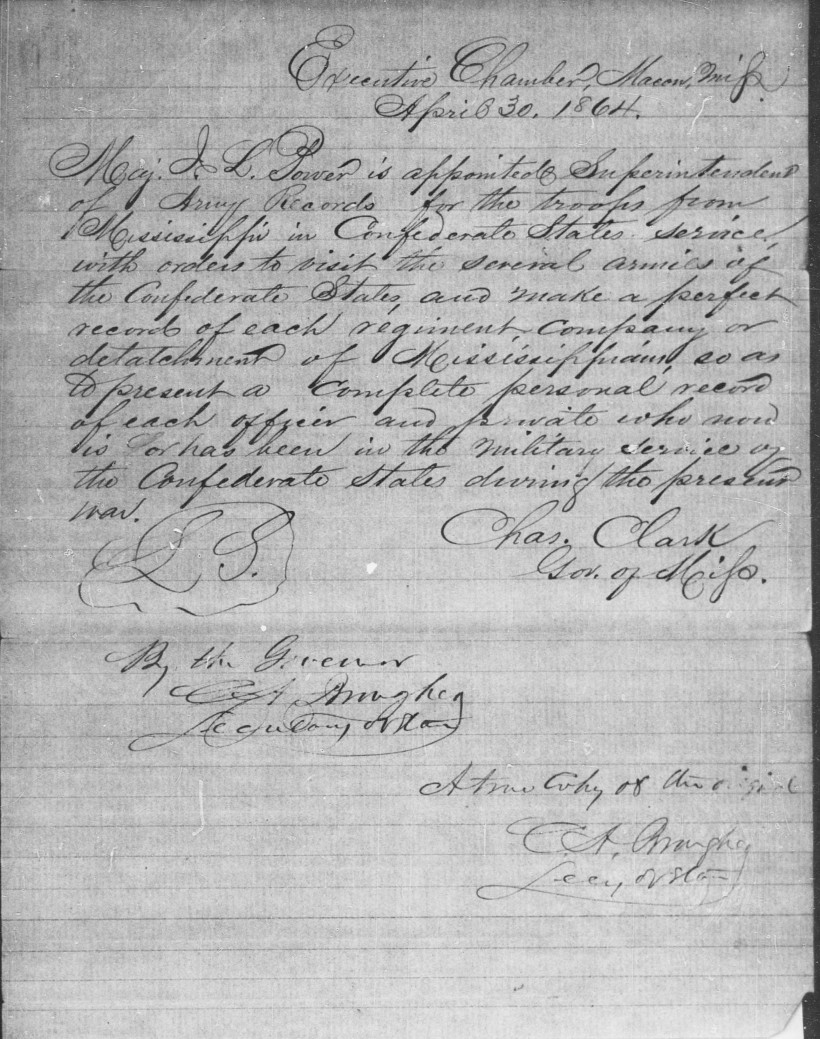

Responding to this legislation, in April 1864, Mississippi governor Charles Clark appointed Major John Logan Power, adjutant of the 1st Mississippi Light Artillery, to the position, which would be known as “Superintendent of Army Records.” Power immediately sent in his resignation as adjutant of the 1st Mississippi Light Artillery to take up his new post. (Compiled Service Record of John L. Power, 1st Mississippi Light Artillery, accessed on Fold3.com).

The job assigned to John L. Power was massive; in a post-war speech for the veterans of Humphrey’s Mississippi Brigade, he explained that it was the “duty of that office to collect and place in a form for permanent preservation and reference, the names of all Mississippians in the Confederate service, with the personal and military status of each; also to procure from the Commander of each Company a certified statement of the amount due each deceased soldier, and to place the same in a shape for settlement…and although I labored faithfully until the general surrender of our armies, yet I found so many obstacles to the successful prosecution of my duties that I was able to accomplish but comparatively little. To enter upon the compilation of these records, after more than three years of active military operations, involving the loss of company books and muster rolls, seemed indeed a hopeless, endless task; and in order to attain anything like accuracy, it was necessary to visit the camps, explain what was wanted, furnish blanks, and assist in filling them out.” (The Clarion-Ledger, May 26, 1880.)

The task set before John L. Power was daunting, but he went to the work with a will. In December 1864 he traveled to Richmond to begin documenting the casualties of those Mississippi units serving in the Army of Northern Virginia. The war ended before he could complete this task, but he was able to compile casualty figures for Humphrey’s Mississippi Brigade:

Colonel Power said of his time with Humphrey’s Brigade, “My first visit was to the gallant brigade, so long, and so ably commanded by him who presides over this meeting to-day. Four years of active war had made sad havoc in the ranks of the four regiments composing it. Of more than five thousand names on the muster rolls since the organization of each command, not exceeding four hundred now answered to the bugle-call for dress-parade. Where were the absent? A glance at the tabular statement herewith submitted, shows that nearly two thousand were in their graves – that they had fought their last battle – that no “sound should awake them to glory again.” (Clarion-Ledger, May 26, 1880)

Although the war ended in 1865, Power’s work on behalf of Mississippi’s soldiers

continued into the next year. In 1866 the state legislature passed an act instructing the Superintendent of Army Records to determine the number of Mississippi veterans requiring artificial limbs. Upon completion of this task, Power reported to the legislature that thirty-six counties answered his request for information, listing 188 soldiers in need of artificial limbs. The colonel went on to speculate that the total number of veterans needing artificial limbs in Mississippi was in excess of 300. (Natchez Daily Courier, October 23, 1866)

Although he went on to bigger and better things (including being elected Mississippi’s Secretary of State twice,) J.L. Power never gave up on documenting the service of the Magnolia State’s Civil War soldiers. Using the documentation he had put together during his time as Superintendent of Army Records, Power drew up an estimate of Mississippi’s total military losses during the Civil War. The totals were as follows:

WHOLE NUMBER IN SERVICE: 78,000

DIED OF DISEASE: 17,500

KILLED AND DIED AFTERWARDS: 15,000

DISCHARGED, RESIGNED, RETIRED: 19,000

DESERTED OR DROPPED: 6,000

MISSING: 250

TRANSFERRED TO COMMANDS IN OTHER STATES: 1,500

TOTAL LOSS FROM ALL CAUSES: 59,250

BALANCE ACCOUNTED FOR: 18,700

(Casualty figures are from The Clarion-Ledger, May 26, 1880)

Colonel Power also felt it necessary to give his thoughts on the Mississippians who deserted from their commands:

“It is proper to remark that a large per cent of those reported as deserters were not such in the most odious sense of that term. Indeed I do not think that more than one thousand of the entire number of volunteers from Mississippi deserted to the Federal lines. Our reserves for the last two years of the war, the despondency, speculation and extortion in the rear, the inability of the government to pay the troops promptly, or to furnish them with anything like adequate supplies of food and clothing, the absolute destitution of many families of soldiers, and towards the last, the seeming hopelessness of the struggle, all conspired to depress the soldier’s heart, and causes thousands to retire from the contest when there was greatest need for their services.” (The Clarion-Ledger, May 26, 1880)

John Logan Power passed away on September 24, 1901, while serving in his second term as Mississippi’s Secretary of State. His efforts on behalf of Mississippi’s veterans were noted in his obituary:

“The contributions of Col. Power to Mississippi history have been many and valuable, and

through his efforts much valuable data pertaining to the affairs of the commonwealth would have been lost forever had it not been for his efforts. He has written a large number of articles now on file in the archives of the Mississippi Historical Society, and at the time of death was at work on a large volume history of the commonwealth he loved so well.” (The Weekly Clarion-Ledger, September 26, 1901)

Colonel John L. Power now rests at Greenwood Cemetery in Jackson, Mississippi. It seems very fitting to me that he is buried in a cemetery surrounded by the graves of untold scores of Mississippi’s Civil War veterans.