Civil War Weapons & Equipment of the Vicksburg Campaign

In this posting I will cover the weapons and equipment that were used by both sides during the Vicksburg Campaign. This is by no means a listing of every firearm and every piece of equipment that would have been carried by the typical Yank or Reb. I have simply tried to describe the types of muskets and various pieces of equipment that would have been in widespread use during the campaign.

Background on Civil War Firearms

Prior to the Civil War, most military firearms used in the United States were smoothbore muskets. They fired a round ball, were most commonly of .69 caliber, had an effective range of 50 yards, and a maximum range of 100 yards. A well-trained soldier could fire 3 – 4 rounds per minute with this type of weapon.

Rifled firearms were not widely used by the military before the Civil War. They fired a patched, round ball, and were accurate out to several hundred yards. The tradeoff was rate of fire: the best that could be expected was one round per minute.

Widespread use of the rifle by the military came after the invention of the Minie ball by

French Captain Claude Minie. He created an elongated lead bullet with a hollow base that was smaller than the bore of the rifle. When fired, the propellant gasses expanded the hollow base of the bullet, expanding it into the rifling of the barrel. With the Minie Ball, firearms could be built with the accuracy of a rifle but with a rate of fire of 3 – 4 rounds per minute. The smoothbore musket was suddenly obsolete.

The United States army adopted the rifle as its primary shoulder weapon in 1855. The changeover to the new technology was slow, however, and when the Civil War began in 1861, both the North and the South had arsenals full of old smoothbore weapons. All of the muskets each side had on hand were not enough, however, to arm the thousands of young men flocking to recruiting stations to join the military. Both North and South were forced to rely on imported weapons from Europe to help equip their men.

Loading and firing a musket, whether it was smoothbore or rifled, was a complex task requiring nine separate steps. A well-trained soldier was expected to take three aimed shots per minute. The cartridges for muzzleloading firearms were made out of paper, and each contained one lead bullet and the blackpowder for the round. In rifled weapons the most commonly used round was the minie ball, and the most common calibers were .58 and .69. Union-made minie balls typically had three rings, while Confederate made minie balls had two rings or no rings. In smoothbore weapons most commonly used were a .69 roundball or a .69 caliber buck and ball round.

Firearms used by the Union army during the Vicksburg Campaign

By the time of the Vicksburg Campaign the North was able to supply three-quarters of its regiments with state-of-the-art first-class muzzleloading muskets. About one-quarter of the army were armed with second-class muskets of both European and American design. Many of the American-made weapons were older smoothbores that had had their barrels rifled to increase their accuracy and range. While they were serviceable weapons, they were not considered as accurate or reliable as first-class weapons. Only one unlucky regiment in the Union army at Vicksburg was armed with third-class arms: the 101st Illinois Infantry had smoothbore muskets.

After the siege of Vicksburg ended, General Ulysses S. Grant allowed his regiments that were armed with second-class or third-class weapons to pick through the captured Confederate stockpile of muskets and take their pick of the many first-class rifles that were available.

U.S. Model 1861 Springfield Rifle-Musket

The Springfield Model 1861 Rifle-Musket was the most widely used Union firearm of the war, and was very well regarded for its accuracy and reliability. The United States Armory at Springfield, Massachusetts, produced over 250,000 of these weapons during the first two years of the war. The government also allowed private manufacturers to build the weapon, as the Springfield Armory could not keep up with the demand. Over 20 different contractors made the Springfield, turning out a total of 450,000 rifles. The Springfield Model 1861 was 56 inches long, weighed nine pounds, and used a .58 caliber minie ball.

British Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle-Musket

The Pattern 1853 Enfield was the standard shoulder weapon of the British army from 1853 – 1867. It was a very well made firearm that was the equal of the Springfield Model 1861 in terms of performance. It was the Union army’s second-most widely used musket, with over 500,000 imported during the war. The rifles brought to the United States were made by a number of civilian contractors in Great Britain. The Enfield was 55.3 inches long, weighed nine pounds, and used a .577 caliber minie ball.

Sharps Carbine

The Sharps Carbine was one of the most popular weapons used by Union cavalry during the Civil War. It was a breechloading weapon that was highly thought of for its reliability, accuracy, and high rate of fire. Unlike a musket that had to be loaded from the muzzle with a ramrod, the Sharps loaded from the breech. By lowering a lever, the breechblock of the gun dropped down, allowing the user to insert a cartridge directly into the breech of the gun. When the lever was raised, the gun was ready to fire. A well trained trooper with a Sharps could fire 10 aimed shots per minute, in comparison to a musket’s three shots per minute. The tradeoff was range: the carbine’s barrel was not as long as the musket’s, so it had a much shorter effective range. The Sharps was 39 inches long, weighed seven pounds, and used a .52 caliber bullet.

Colt Model 1851 Navy Revolver

A six-shot, single action revolver (single action means the hammer has to be pulled back before the trigger is pulled), the Colt Navy was one of the most widely used handguns of the war. Issued primarily to cavalry, they provided multiple shots at close range, which were very useful as troopers often fought at close range. These weapons were also used as personal side-arms by many Union officers. The Colt Navy was 13 inches long, weighed 2 pounds, 10 ounces, and used a .36 caliber conical or round ball.

Colt Model 1860 Army Revolver

A six-shot, single action revolver, the Colt Army was one of the most popular handguns used during the Civil War. They were widely issued to the cavalry, where the multiple shots and heavy firepower they provided for close-range engagements made them a formidable weapon to be reckoned with. Like the Colt Navy, officers often used these revolvers as their personal side-arms. The Colt Army was 14 inches long, weighed 2 pounds, 11 ounces, and used a .44 caliber conical or round ball.

Remington Model 1861 Army Revolver

A six-shot, single action revolver, the Remington Army was the most widely used handgun of the war. The United States government purchased 125,314 Remington Army Revolvers. The Remington had an advantage over the Colt Army, in that it was much less expensive. The Remington was 13.75 inches long, weighed 2 pounds, 14 ounces, and used a .44 caliber conical or round ball.

Firearms used by the Confederacy during the Vicksburg Campaign

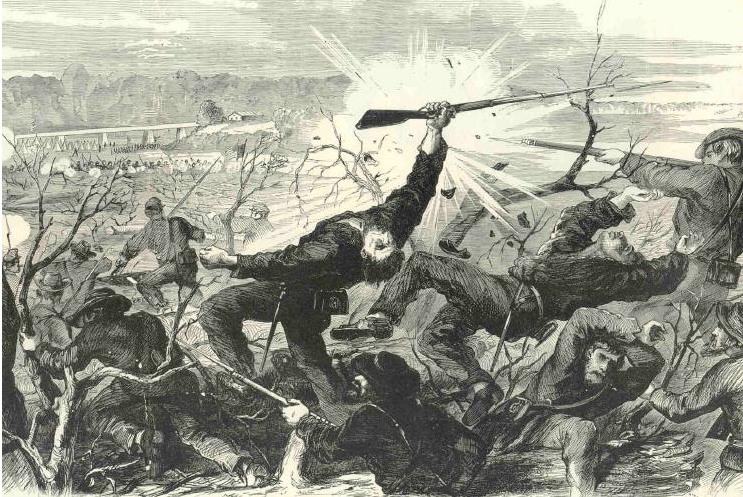

The Rebel soldiers who fought in the Vicksburg Campaign were armed with a variety of firearms of Confederate, European, and United States manufacture. Whereas the Union infantry at Vicksburg almost exclusively carried rifle-muskets, their Southern counterparts had a large number of smoothbore muskets in addition to their rifles. Many of the smoothbores were stacked in the trenches during the siege to give the infantry increased firepower during Union assaults.

When the Vicksburg garrison surrendered on July 4, 1863, a huge amount of ordnance fell into Union hands: 50,000 firearms, and 600,000 rounds of ammunition were among the windfall. A reporter for the Chicago Tribune viewed the captured stockpile and wrote: “The number of muskets and rifles taken will far exceed the number of prisoners. Each man in the trenches kept two, three or four double loaded for use in case of assault. The men used ordinarily English rifles. The extra guns were mostly Springfield and Harper’s Ferry muskets.”

British Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle-Musket

The British Pattern 1853 Enfield Rifle-Musket was the most widely used firearm of the Confederates during the Vicksburg Campaign. Enfield rifles were smuggled into the South though the Union navy’s blockade, and they were very well liked by the troops lucky enough to be issued them. The 3rd Louisiana Infantry was issued the Enfield during the Siege of Vicksburg, and William Tunnard, a sergeant in the regiment, wrote that they “Began a brisk fire in their eagerness to test their quality.” The Union soldiers receiving this fire noticed the improved accuracy of the Rebels and “Wished to know where the devil the men procured these guns, and were by no means choice in the language which they used against England and English manufacturers.” The Enfield was 55.3 inches long, weighed nine pounds, and used a .577 caliber minie ball.

U.S. Model 1841 Mississippi Rifle

This rifle was named for the 1stMississippi Regiment that was led by Colonel Jefferson Davis and used the weapons to good effect during the Mexican War. They were originally designed in .54 caliber, but many were modified during the Civil War to .58 caliber. As originally designed they were not intended to use a bayonet, but many had a bayonet lug added during the Civil War so that a sword bayonet could be utilized. The Mississippi Rifle was 48 inches long, weighed nine pounds, and used either a .54 or .58 minie ball.

U. S. Model 1842 Musket

The Confederates had many different models of smoothbore musket that they used at Vicksburg, and one of the most common was the U. S. Model 1842 Musket. The last smoothbore musket adopted for use by the United States, many were in Southern arsenals at the beginning of the war. The musket could fire a single .69 caliber ball, or it could fire what was known as a “buck and ball” load. This consisted of a .69 caliber ball with three buckshot stacked on top of it. Each time the gun was fired, four projectiles were sent downrange, increasing the chances of hitting the enemy. It was a very useful round for close range fighting, and many were used at Vicksburg during the Union assaults on the Rebel earthworks. The Model 1842 was 57 inches long, weighed nine pounds, and used a .69 caliber ball or buck and ball load.

Maynard Carbine

One of the most popular Confederate cavalry weapons of the war was the Maynard Carbine, a breechloading single-shot rifle. Unlike most Southern carbines that used paper or linen cartridges, the Maynard used a metallic cartridge with a small hole in the base that was ignited by a standard musket percussion cap. A rugged weapon, the Maynard was known for its reliability and ease of use in combat. Before trade was cut off with the North, the states of Georgia, Florida, and Mississippi purchased 2,369 of these weapons from their manufacturer, the Maynard Arms Company. A columnist for the Oxford Intelligencer in Mississippi wrote that there was “Nothing to do with [the] Maynard rifle but load her up, turn her North, and pull trigger; if twenty of them don’t clean out all Yankeedom, then I’m a liar, that’s all.” The Maynard was 36 inches long, weighed six pounds, and used a .50 caliber metallic cartridge.

Griswold & Gunnison Revolver

Confederate cavalrymen loved the Colt Model 1851 and 1860 revolvers and used them whenever possible. But there were never enough of them to go around, and the Southerners resorted to producing copies of the Colt pistols. One of the most widely used was the Griswold & Gunnison revolver that was made in Griswoldsville, Georgia. From 1862 – 1864, 3,606 of these pistols were produced. They were a close copy of the Colt Model 1851 Navy, the major difference being that the Confederates had to substitute brass for the frame instead of steel. The Griswold & Gunnison was 13 inches long, weighed 2 pounds, 6 ounces, and used a .36 caliber round ball.

Equipment used by Union and Confederate soldiers during the Vicksburg Campaign

Union and Confederate soldiers in the midst of an active campaign had to carry all of their equipment and personal belongings on their backs. They quickly learned to pare down the weight and carry only those items that were absolutely essential. Even with a light marching load, the typical soldier was still carrying 40 – 50 pounds of equipment. This was as much as most soldiers could carry on a daily basis without placing too great a burden on themselves. The typical items carried by Union and Confederate soldiers were:

Knapsack

Used like a modern backpack, the knapsack held rations, extra clothing, blankets, and any other odds and ends that the soldier wanted to carry with him. They were not widely used by Confederates during the Vicksburg Campaign, who preferred to carry their extra gear in a blanket roll. The most common Union knapsack was the Model 1855 double bag cloth variety, painted black to make it somewhat resistant to water. Many Union soldiers also preferred the blanket roll, and threw away their knapsacks at the first opportunity.

Blanket

Army issued blankets were typically made of wool and were either carried in the knapsack or rolled up, the ends tied together, and worn over the shoulder as a blanket roll. For Confederates, army blankets were often in short supply, so it was common for them to use civilian blankets or captured Union blankets. Federal soldiers were commonly issued gray wool blankets with “U.S.” stitched in the center and dark stripes on either end.

Haversack

The haversack was a cloth bag with a strap so that it could be worn over the right shoulder with the bag resting on the left hip. The Confederate model was usually of unpainted white cotton, while the Union version was generally painted black to give it some resistance to water. The haversack held the soldier’s rations and eating utensils.

Canteen

Confederates were often issued round, drum-shaped canteens made of tin or wood. They also used captured Union canteens whenever they could acquire them. Union soldiers were issued tin canteens with an oblate shape. There were two versions, one with smooth sides, and the other with a bull’s eye pattern of rings impressed on both sides. Some were issued with a woolen cover that was brown or various shades of blue.

Cartridge Box

Confederate cartridge boxes were made from leather or painted cloth, and some held 40 rounds of ammunition. Others imported from Great Britain held 50 rounds. They could be worn either from a sling over the shoulder, with the box on the right hip, or attached to a belt and worn around the waist. Union cartridge boxes were made out of leather, held 40 rounds, and typically had a “U. S.” boxplate on the front cover to keep the flap closed. They were usually worn from a sling that had an eagle breastplate attached.

Equipment Belt

During the Civil War soldiers did not use belts to hold up their pants – they had suspenders for that. Belts were used to hold an infantryman’s cap box, bayonet, and sometimes the cartridge box as well. Officers and non-commissioned officers might also have a sword suspended from their belt. Confederate belts were made from leather or painted cloth. The most common buckle was a simple frame style, but beltplates with “C.S.,” or “C.S.A.” were also used. Union belts were leather with an oval “U.S.” buckle. Officers and non-commissioned officers wore rectangular sword belt plates with an American eagle inside a wreath on the front.

Cap Box

The cap box was worn on the belt and used to hold the copper percussion caps needed to fire the musket. Confederate models were leather or painted cloth. Union models were made of leather.

Bayonet

Worn on the equipment belt, the scabbard for the bayonet was typically made of leather with a brass finial on the end. Some Confederates did not carry bayonets, but those that did used a wide variety of triangular socket bayonets and sword bayonets. Union infantry typically used a triangular socket bayonet, but some units did have rifles that needed a sword bayonet.