Control of the mighty Mississippi River was of vital national interest to both the Union and the Confederacy during the Civil War. By the spring of 1862 the fight for control of the Mississippi focused on Vicksburg, the last major Confederate outpost on the river. The conflict soon spilled over into the Yazoo River and its tributaries, and by the time the Hill City fell in 1863, the brown waters of the Mississippi Delta was littered with both military and civilian vessels. When the war ended the armies went away, but the vessels lost during the fighting remained in their watery graves, where they could be extremely hazardous to civilian river traffic. On January 1, 1870, The Tri-Weekly Clarion of Jackson, Mississippi, published this guide to the wartime wrecks on the Yazoo, Tallahatchie and Yalobusha rivers under the title, “Interesting Reminiscences of the War:”

Many scenes of exciting interest transpired during the recent civil war that never have and never will be told. The line of the Yazoo, Tallahatchie and Yalobusha Rivers was a field of incident that has so far almost escaped the notice of reporters. Numerous vessels, owned chiefly by Southern boatmen, sought refuge in the streams named. As the Federals forced Southerners backward in their determined effort to capture and control the Mississippi and its tributaries on the eastern side, steamers huddled closer together like so many frightened sheep. Finally, when it was found impossible to save them from capture, the torch was applied, and great havoc resulted. Thirty-three steamers were given to the flames, among them many of the largest, fleetest and costliest that ever floated on the waters of the west. The line of the river was lurid with the glare of many burning steamers. Its course could be traced for days after by the dense clouds of black smoke that hung like a funeral pall over the wrecks that now lie scattered at intervals along the river.

At several points vessels were moored side by side before destruction, that their sunken hulks might obstruct the channel and prevent the advance of the enemy’s fleet. At low stages of the river these wrecks now impede navigation, though they do not entirely prevent the passage of steamers. A recent visit to the locality enables us to give the following account of the situation:

In the upper Tallahatchie River, and 120 miles from its mouth at Jarmyn’s lies the wreck of the Cotton Plant, formerly Flora Temple. She was burned where she lies in July, 1863, and is no obstruction to navigation. At Sam Evan’s place, sixty miles lower down, the wreck of the Hartford City lies close to the bank, and out of passing steamers’ way.

At Fort Pemberton, six miles above the entrance of the Tallahatchie into the Yazoo, the wreck of the famous steamship Star of the West lies where she scuttled and sunk, directly in the middle of the river, and a dangerous obstruction to passing steamers. The engine walking beam, greatly injured by rust, and one weather-beaten wheel-house of this monster steam-ship stand high above the level of the river, to warn approaching vessels from above or below that they must give the wreck as wide a berth as possible. The channel at this point admits only a few spare feet on either side, while the current is swift as a mill-race, and pilots must exercise their best care and skill to make the run successfully. The Star of the West, it will be remembered, was driven to sea, off Charleston harbor, by Confederate batteries, when making an effort to provision Fort Sumter, and caused the firing of the first gun of the war. She was afterwards captured off Galveston, Texas, by Van Dorn and a party of Confederates under him, carried into New Orleans, and finally up the Yazoo. She was an unlucky vessel, and never did the Confederates any good, except to entail expense in caring for her. The blackened hulk and rusty, weather-beaten machinery may lie for ages in their present position, a fitting emblem of her useless career.

Up the Yallabusha, one mile from its mouth, lies the wreck of the Ferd. Kennet, once a fine St. Louis and New Orleans steamer, scuttled and burned in 1863. Navigation is unimpeded by this wreck. The Ed J. Gay, another elegant St. Louis steamer, lies directly at the mouth of the Tallahatchie and Yallabusha, close to the eastern bank of the Yazoo. Ample space is afforded passing steamers. A mile and a half below lies the wreck of the Acadia, in times ante bellum a favorite and well known New Orleans and Coast packet. Her wreck lies directly in the middle of the river. Steamers must feel their way carefully when passing by.

The remains of the Mary E. Keene, once the pride of the Vicksburg packets, are at French Bend, fourteen miles below Greenwood. The wreck is

close against the bend, and is no obstruction to navigation. At Browning’s Bar, twenty-five miles below Greenwood, four wrecks lie side by side, bows down stream, in the exact position where they were sunk to prevent the ascent of the Federal fleets. The Scotland is near the western bank, next the Golden Age, then the R. J. Lackland, and on the eastern bank the John Walsh is planted. These wrecks are all plain to view, except, the Golden Age, from under which the sand has washed, or suing the wreck to settle so far beneath that steamers pass directly over her without danger.

The great Natchez, one of the finest steamers ever constructed, and converted into a ram, was burned and destroyed with 1200 bales of cotton on board at Burtonia, eighty miles above Yazoo City. Sixty miles farther down, and within nineteen of Yazoo City, is the wreck of the Peytona: ten miles below is the Prince of Wales. The J. F. Pargoud, regarded by many boatmen as without a superior in point or symmetry and beauty, lies three miles farther down.

The Magenta and Magnolia, both of huge size and capacity, lie six miles above Yazoo City. Just below lies a Federal tin-clad gunboat, the Number 5, captured and destroyed here by the Confederates. The Baron DeKalb, a Federal iron-clad, was blown up and destroyed by a torpedo half a mile below Yazoo City. The Confederate gunboat Mobile was burned near the same spot. Both wrecks lie out of the channel. The Republic and Alonzo Child lie near here, their machinery having first been removed to Selma, Ala., where it was afterwards placed in Confederate gunboats.

At Liverpool Landing, some twenty miles below Yazoo City, several vessels were scuttled and burned. Among them was the famous Capitol,

owned at Memphis, and which, during the summer of 1860, made thirteen successive weekly trips between Memphis and New Orleans. The gunboat V. H. Joy also lives here: first as the Roger Williams, noted for speed in New England waters, then as the El Paraguay, a South American gunboat, again as a towboat, towing ships between New Orleans and the Gulf, then transformed into a Confederate war vessel and as Hollins’ flag ship, making rapid dashes in front of the enemy about Cairo and Bird’s Point. Her career was surely an eventful one. Her hull lies in a dangerous position, causing passing steamers to work with caution in making the run up or down.

The gunboats Lady Polk, Maurepas and Van Dorn are also sunk here. The latter, once well known as the towboat Junius Beebe, and one of the best vessels of her class ever constructed, was built at New Orleans in 1854. With low-pressure machinery of great power, she was one of the fleetest and handsomest vessels that ever dashed past the shipping in front of the Crescent City. The Lady Polk was known in earlier days as the Nashville steamer Ed Howard, and latter as one of Hollins’ gunboat fleet.

At Snyder’s Bluffs, below, is the hulk of the iron-clad Cairo, blown up by a Confederate torpedo. These with the Hope and Ben McCulloch, afterwards raised; comprise all the vessels destroyed during the war on the Yazoo. Many have since been dismantled, and their machinery removed by the U.S. Government. Several still have their machinery on board; and are either disputed or private property.

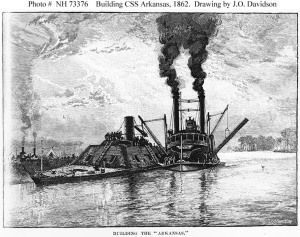

In addition to the above, the H. D. Mears, Emma Bell and Argo were destroyed up the Sunflower, and the Dew Drop up Quiver, one of its affluents. Near the bridge crossing of the Vicksburg Railroad to Jackson, on Black River, the steamers Charm and Paul Jones were burned. The gunboat Arkansas, built at Memphis, and completed in Yazoo, was blown up just above Baton Rouge at the time it was attacked by Breckinridge in 1862. A huge war vessel was burned on the stocks half finished, at Yazoo City. These complete the list.