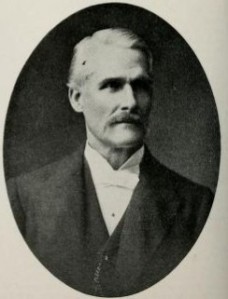

While doing some research recently I found a very interesting memoir written by Louis J. Frederic, who served in Company L of the 27th Mississippi Infantry. It was published in the Times-Picayune of New Orleans on December 7, 1896. Entitled “A Soldier’s Diary of the Civil War,” it is, in fact, not a diary, but a memoir written by Frederic after the war, likely using letters or a diary as his source material. The manuscript was published shortly after the death of Frederic, and the following introduction told how it came to be printed in the newspaper:

Not so very long ago the veterans of the Army of Tennessee were called upon to mourn the loss of a loyal comrade in L.J. Frederic. In order to express in some measure the regret at the passing away of their friend, the grand old association appointed a committee to prepare resolutions to enter upon the records and to form a priceless keepsake for the family of the departed hero. Dr. C.H. Tebault, now surgeon general of

the Confederacy, who knew Mr. Frederic well, was one of the committee, and happened to make an examination of the papers which the deceased left behind. Among them he discovered a curious and valuable document. It was a brief but complete history of the war insofar as Mr. Frederic had to do with it. The young soldier had kept a diary of the various epochs in his battle career, and the whole made up a rare chronicle in the annals of warfare. There was no comment, no criticism, simply a bare, unvarnished tale, and it is well worth a place among the relics in Memorial Hall. Mr. Frederic’s Diary is as follows:

In the month of September, 1861, a meeting was held near Moss Point for the purpose of organizing a company of volunteers for service in the Confederate states army. The following officers were elected: H. Bruno Griffin, captain; Thomas K. Hawkins, first lieutenant; Samuel Johnson, second lieutenant; Aristides Krebs, brevet second lieutenant. The company was named Twiggs Rifles in honor of Major General Twiggs, then commander of the department.

On Oct. 2, 1861, the company was mustered in the service of the Confederate states for one year. Remained in camp at Pascagoula until the 24th of February, 1862. Marched to Fowl River, Ala., thence to Cedar Point, Ala. Remained there two months. On the 4th of May moved to Mobile.

The company was now mustered in service for three years, and was reorganized, electing as officers H.B. Griffin captain; Samuel Johnson, first lieutenant; Jesse Thompson, second lieutenant; and Wm. Welch junior second lieutenant. Lieutenant Hawkins and Krebs withdrew from the company and enlisted in Morgan’s cavalry.

The company was now attached to the Twenty-Seventh Mississippi Regiment, Mississippi Volunteers, and designated as Company “L.” The Twenty-Seventh Mississippi Regiment was part of Jones’ brigade, then camped on the bay shore, about two miles from Mobile. July 24, 1862, was ordered to Chattanooga, Tenn. Aug. 4 was ordered to Graham Station on the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad, for picket duty on Long Island, in the Tennessee River, to prevent a corps of the federal army, then occupying Bridgeport, Tenn., from crossing at this point.

Aug. 20 returned to Chattanooga, crossed the river, camped at the foot of Walden’s Ridge

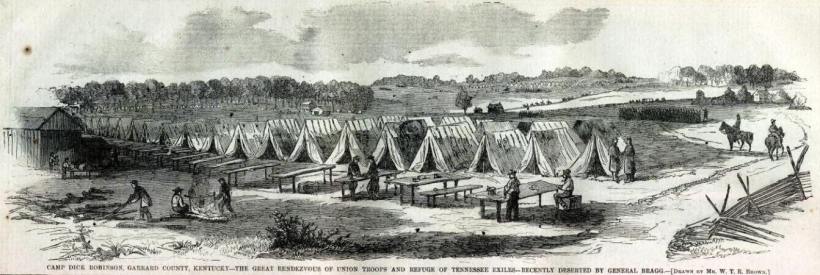

and prepared for the march through Tennessee and Kentucky. Jones’ brigade was attached to Pat Anderson’s division. Sept. 1, 1862, moved from camp and began the long and fatiguing march over Walden’s Ridge and over the Cumberland mountains, without rest, until reaching Bardstown, where the army rested ten or twelve days. Marched as far as Harrodsburg, and then returned to Perryville to face the enemy under General McCook. Oct. 8, battle of Perryville, Private Louis Wells was killed, being the first man of the company killed in battle. Several men were wounded, Wm. Wiley Goff dying of heat and fatigue. Remained on battle field all night. Marched to Harrodsburg, where the wounded were left in hospital. Marched to Bryantsville and camped there several days at Camp “Dick Robinson.” Marched through eastern Kentucky and crossed the mountains at Cumberland gap.

Marched to Knoxville, Tenn., arriving there on the 23d of October, 1862. Oct. 24 a heavy snow storm, from which the company suffered a great deal, occurred, many of the men having no shoes and only the clothes with which they had started on the campaign; very few had blankets. From Knoxville moved by railroad to Chattanooga and thence to Shelbyville, Tenn. Marched to Eagleville.

General E.C. Walthall now took command of the brigade, which afterwards became famous

as Walthall’s brigade. On Dec. 25 marched to Murfreesboro and participated in battle Dec. 30 and 31, 1862, and Jan. 2, 1863. Sergeant Antonio Baptiste was killed in the ditch on the evening of Dec. 30, a solid four-pound shot fracturing his skull. Several others were wounded and sent to hospital. On Jan. 2 the men, wet by the rain which had been falling all day, and nearly frozen by the intense cold, were ordered to leave the line of battle and, marching through rain and mud, reached Shelbyville at night. Here the army went into winter quarters. J.A. McInnis was elected second lieutenant in place of Jesse Thompson, who had died in hospital at Chattanooga, after the return from Kentucky.

On the 2d of May the brigade was ordered to Louisburg, Tenn. On the 25th of May a match drill was held, in which Company “L” won first prize – ninety days exemption from duty. Lieutenant Welch, commanding the company, was presented with a sword, and a general order was read, in which General Walthall complimented the company for its skill. On May 27 returned to Shelbyville; from there marched to Tullahoma and over the Cumberland mountains, crossed the Tennessee River on pontoons and arrived at Chattanooga on July 4, 1863. Ordered to Chickamauga Station, where the brigade was attached to Liddell’s corps.

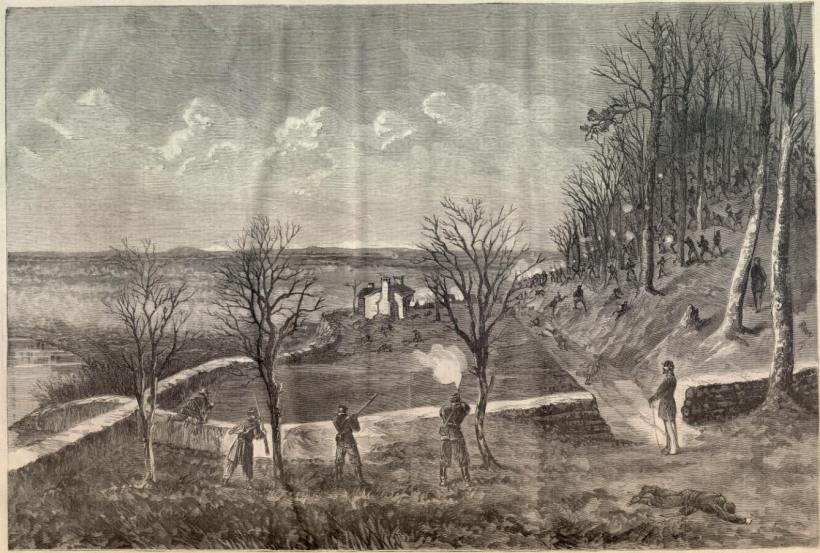

Marched to Lafayette, Ga., and to McLemore Cove to stop the advance of the union army in that direction. The enemy having withdrawn, Liddell’s corps marched back to Chickamauga Station, engaged in battle on the 19th, 20th and 21st of September, advanced to Missionary Ridge, where the brigade remained in line of battle during the month of October and part of November. About the middle of November camped on top of Lookout Mountain. On the 24th participated in the battle of Lookout Mountain. Lieutenant Samuel Johnson and Sergeant Hughie Goff were killed.

Captain Griffin, Lieutenant McInnis and sixteen men were taken prisoners. On Nov. 25 participated in the battle of Missionary Ridge. On Nov. 26 the army retreated to Dalton, Ga., and went into winter quarters. This being a very severe winter, the men suffered a great deal from cold and frequent snow storms.

On May 7, 1864, formed line of battle near Bald Face Mountain. The enemy having left, the brigade was ordered to fall back to Tipton, Ga. Marched to Resaca, Ga., and participated in battle May 14 and 15, retreating during the night and skirmishing during the day. Participated in battles at Cassville, Lost Mountain, Kennesaw Mountain, Good Hope Church May 25 and 28; was wounded here, at Culp Farm, near Marietta, June 22, 1864.

The army continuing the retreat, entered Atlanta on July 9. Atlanta was now closely invested by General Sherman, a constant bombardment being kept up night and day. Engaged in battle at Peach Tree Creek on July 22 and along the lines July 28 to Aug. 3, at Jonesboro Aug. 31 and Sept. 1. Private Milton Evans was killed on Aug. 31.

Having now evacuated Atlanta, marched toward northern Georgia, engaged in the battle of Snake Creek gap Oct. 12, 1864; Private James Simmons was killed there; Florence, Ala., Nov. 6; Franklin, Tenn., Nov. 30; Nashville, Tenn., Dec. 12-15; Private William Saulsbury killed Dec. 12. Retreating from Tennessee, arrived at Bruensville, Miss., Dec. 31, 1864, where the company was mustered for pay. Marched to Tupelo, Miss., and camped there several days. On Jan. 18, 1865, moved by rail to Meridian, Miss.

On Jan. 28 the brigade was furloughed for fifteen days, the men of Company L going to their homes in Jackson County, Miss. Returned to Meridian Feb. 12. Feb. 19 ordered to Montgomery, Ala. On Feb. 28 company mustered, showing present for duty one first lieutenant, two sergeants, and four privates. Ordered to North Carolina, going by rail as far as Augusta, Ga., and marching from there to Smithfield, N.C., the effective strength of the regiment being now so reduced that it was found necessary to reorganize and reduce the regiment to two companies. Six companies, including Company L, were made Company “G,” Twenty-Fourth Mississippi, the Twenty-Seventh regiment ceasing to exist April 10, 1865. The officers appointed to Company “G” were: Ed D. Stafford, captain; William Welch, first lieutenant; Thomas Bailey, second lieutenant.

From Smithfield marched to Fayette, N.C., and fell back to Greensboro, where the brigade was put on duty as provost guard. On the 26th of April, 1865, the army surrendered. The officers and men each received out of the Confederate treasury $1___, nearly all in Mexican coin. May 1, 1865, the men received their parole papers. May 3 started on the return homeward, marching through North Carolina and South Carolina to Washington, Ga., and going by rail to West Point, Ga., marching to Montgomery, Ala., and taking boat down to Mobile and marching to Pascagoula. Lieutenant Welch, Sergeants L.J. Frederic and Andrew Vaughan, Privates Simon Cunningham, L.J. Dupont, Charles Hawkins, and William Passaw, seven out of 118 who had belonged to the company since its organization, returned home from the army, the others having been killed in battle, taken prisoners, died in camps and hospitals, discharged from the service, and some in hospitals, sick or wounded, at this time.

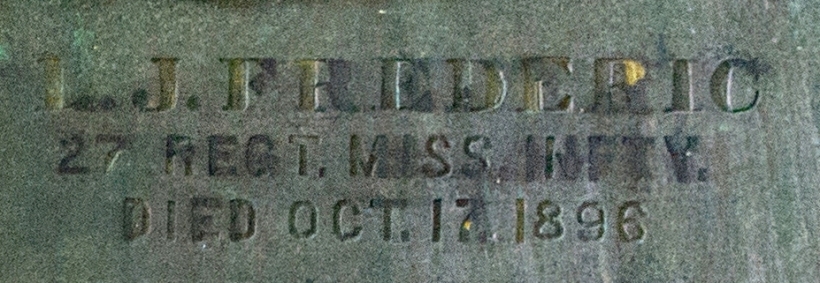

Louis J. Frederic’s full name was Louis Jefferson Frederic de St. Ferol, and he was born about 1832 in Pascagoula, Mississippi. According to a family history that I found online, his father had served in the French army during the Napoleonic wars, and immigrated to the United States in 1820. Louis moved to New Orleans after the war, and went into the cotton business. He died on October 17, 1896, and is buried in Metairie Cemetery.