On May 3, 1864, the Union host encamped around Chattanooga broke from their winter quarters and began the campaign to tear the heart out of Confederate Georgia.[1] The sight of thousands upon thousands of blue – clad troops marching south inspired Charles Capron of the 89th Illinois to write: “by one o clock you could see long lines of infantry winding their way over hill and valley like the large Boa Constrictor rushing with irristible force on to their intended victim.”[2]

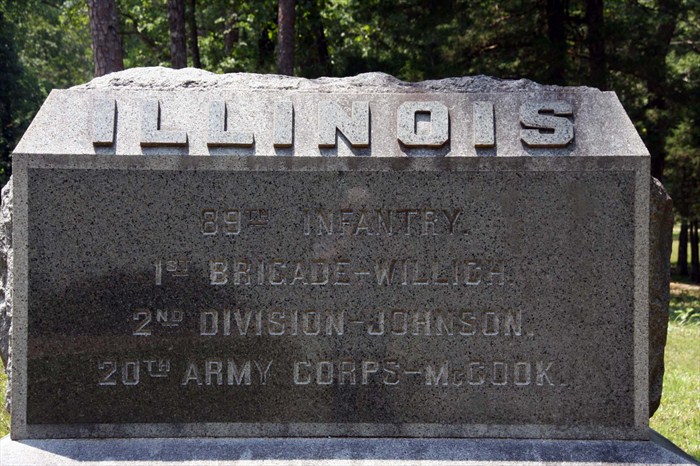

Although he had been in the army for less than ten months when he started down the long bloody road to Atlanta, Capron was already a veteran campaigner. He had his baptism of fire at Chickamauga barely more than a month after joining the army, and surviving the crushing Union defeat, joined in the retreat back to Chattanooga. Once there he endured hunger and privation as the Rebels invested the city, and after a long bitter siege he had his first taste of victory as the Army of the Cumberland charged up Missionary Ridge and smashed the Confederate line, sending the Rebels fleeing and ending the threat to Chattanooga. The men of the 89th Illinois had little time to enjoy the fruits of their victory as they were immediately sent with a force to relieve the Union garrison at Knoxville Tennessee, under siege from Confederates commanded by General James Longstreet. The relief column arrived after the Confederates retreated, and the 89th did not see any significant combat for the remainder of 1863. The only fighting they had left was against the elements as they spent a very bleak winter on the march through East Tennessee. [3]

As winter slowly gave way to spring, Capron realized the time for the army to move against the Rebels was close at hand. He acknowledged this in a letter he wrote to respond to his mother’s worries that he did not have enough warm clothing, saying:

You was thinking that I have not clothes enough you must remember that it is getting warm weather here now and if we march much I will have to throw some of them away I would like to send home a good overcoat that I do not need but there is no chance.[4]

While he did try to allay his mother’s fears in his letters, Capron had reservations about the upcoming campaign – in a very short time he had learned the hardships of a soldier’s life, and thoughts of trying to find an easier place in the army did cross his mind. He wrote in late March:

I think some of going into a cavalry regiment that is going into Texas I think that I can stand it better in mounted service if I can get out of this regiment but as long as they lay here I am satisfied…[5]

Joining the cavalry may have been an idle fancy, as there is no indication in his service record that Capron ever actively sought a transfer.[6] A few weeks later he heard a rumor that his division was to be assigned to garrison duty which would keep them safely away from the front lines, but he looked at this rumor through the jaundiced eyes of a veteran saying, “…there is so many reports that you cannot believe anything you hear and only half what you see at any rate…”[7]

While Capron prepared himself for the combat to come, great changes were being made in

the Union high command. On February 29, 1864, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to Lieutenant General and given control of all the Federal armies in the field. Grant’s new responsibilities required his presence in the Eastern theatre, so General William T. Sherman was given command of the Military Division of the Mississippi to take charge of the Western theatre.[8]

After receiving his promotion, Grant wasted little time in formulating a plan to destroy the Confederacy and end the war. Grant and the Army of the Potomac had the objective of destroying Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and taking Richmond; at the same time, Sherman would move against Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee and capture Atlanta. With both Union forces, east and west, moving at the same time, they would keep the pressure building against the Confederates until they ultimately collapsed from the strain.[9]

By the time he was ready to move against the Rebels in early May, Sherman had at his

disposal a very powerful force, consisting of the Army of the Tennessee, commanded by General James B. McPherson, the Army of the Cumberland, commanded by General George Thomas, and the Army of the Ohio, commanded by General John M. Schofield. All told, Sherman had approximately 100,000 men under arms to use against Johnston’s Rebel army, numbering about 60,000 men.[10]

On May 3, 1864, the 89th Illinois received the news that Capron had been anticipating for so long; their corps had orders to march.[11] The regiment broke camp at McDonald Station, Tennessee, about 20 miles Northeast of Chattanooga and marched south towards the nearby Georgia border. After passing the state line Capron said that he had “crossed on to the sacred soil.”[12]

The Federals were marching for Dalton, Georgia, where Johnston had the Army of Tennessee entrenched just west of town on the craggy heights of Rocky Face Ridge. The Rebel position was a strong one, and Sherman was not anxious to waste lives in a frontal assault. He decided instead to flank Johnston out of his earthworks, and accordingly on May 7th, General McPherson began marching his troops beyond the Confederate left flank to Snake Creek Gap, a route through Rocky Face Ridge that offered access to Resaca, Georgia. If McPherson could take Resaca, Johnston’s railroad supply line to Dalton would be cut, and he would be forced to abandon the city.[13]

At the same time McPherson was making his flank march, General Schofield’s men were marching towards the Confederate left flank, and General Thomas was demonstrating against the Rebel center to keep Johnston at Dalton, unable to interfere with McPherson’s march.[14] Thomas’ men seized the Confederates forward position at Tunnel Hill on May 7, with Capron and the 89th serving as skirmishers while the Federals moved towards the main Confederate line on Rocky Face Ridge. Over the next four days the regiment skirmished with the enemy, providing the distraction their orders called for.[15]

On May 11, Capron found time to pen a letter to his family describing the combat he had seen over the past few days:

Georgia Tunnell Hill May 11, 1864: to the dear ones at home I now seat myself for the purpose of answering your kind letter which I received to day dated May 1th

I am some distance from where I last wrote you for we left Camp Donelson May 3 went about 8 miles and camp there for the night started the next morning came to Catoosa springs and there came to a halt no one dareing to venture through the gap for fear of a massed battery but old Willich our brigade commander came up and said that he would go through with his brigade and through we went driving in the rebels videttes May 5 & 6 laied in camp I will now give it to you day by day as we got it. May 7 advanced about 12 miles to tunnell hill slight skirmishing through the day and some big guns fired. May 8 formed in line of battle the same as yesterday got orders to go on the skirmish line lost 14 men killed and wounded May 10 layed on the reserve heavy skirmishing all day and considerable cannonading May 11 we heard that we could send out letters to morrow so I will finish it this evening I have not time to give all the particulars suffice it to say that we have waded through blood for the last 14 days and are now within 60 miles of Atalanta with the enimy within a mile of us they have disputed our passage every night we have made an avarage 10 miles a day except to days that they made a stubborn resistance I passed over the battle field after the noise was hushed and the dead and wounded that they left in our hands showed how they suffered I remain as yet unhurt Mr Copeland[16] is well he received a letter from amanda yesterday there will be in all probability another big battle before many days and it may not be my lot to come out safe you must write whether you get a letter from me or not for the mail does not go our very regular. I will now close as we are a going on this morning this from your affectionate son

C. C. to M. S. C.[17]

On May 12th, the 89th marched to a new position and began building earthworks, so their skirmishing duty was over for a time. Although Capron made it sound very bloody, the regiment’s casualties were slight – only two killed or mortally wounded.[18]

The Federals had done their job well, but ultimately the effort to distract Johnston had been in vain – McPherson, after making contact with the thin line of Confederate defenders protecting Resaca, believed the Rebels were massed in force against him and withdrew to Snake Creek Gap, leaving the southern supply line intact.[19] Johnston, finally alerted to the threat to his rear, ordered his army to evacuate Dalton and retire to Resaca, a movement that began after dark on May 12.[20]

On May 13, the Federals began their pursuit of the Rebels, the blue columns coming within sight of the Confederate entrenchments at Resaca on the 14th. Sherman ordered his men to attack that day, and at the same time he sent a column to flank the Rebels from their position. Fighting flared again on the 15th, but realizing his position had been turned, Johnston withdrew his army that night.[21]

For the 89th Illinois, the fighting at Resaca never amounted to more than a light skirmish, and losses were negligible – only one man killed or mortally wounded.[22] There was however one other significant casualty of the fighting at Resaca – the 89th’s Brigade commander, General August Willich, was wounded by a sharpshooter on May 15, and command of the brigade fell to Colonel William H. Gibson of the 49th Ohio Infantry.[23]

Capron and the 89th Illinois were on the march again May 16 and 17 as they continued their pursuit of the Rebels.[24] On the 18th Johnston halted his army north of Cassville with the intention of giving battle, but his plan misfired and he withdrew again to the south of the town. The next day he retreated again to the safety of Allatoona Pass and prepared to meet the Federals from this very strong position.[25]

After the Confederate retreat to Allatoona, Sherman allowed his men three days of rest, and Capron took advantage of the opportunity to write home:

May 22th, 1864, Camp Near Kingston

To the remembered ones at home. I now seat myself to answer your kind letter which came to last night dated May 12th I wrote you on the 19 but as we are going to leave in the morning I thought I would write you a few lines I am well at present so is Mr Copeland we have been in camp 2 days but got orders to move in the morning do not know where we will go to some think that we will go on to the Potomac I am as yet one of the favored ones but how long I do not know I received a letter from Annette and Laura dated May 2 it said that they was all well I have not much to write now as I wrote lately I do not know when we will be paied of [f] likely not till this campaign is over they owe us nearly 6 months pay already you must tell Nell Lorain and Arthur to write as you do not know how eager the boys are for the mail if the folks at home could see the boys watch for the mail i am sure they would write oftener but I can think of nothing more to write at present I wrote a letter for Mr Copeland the same day I wrote to you I must quit for this time so good bye for this time from your affectionate son C. Capron to M. S. C.[26]

Sherman put his armies in motion once again on May 23, but the objective was not Allatoona Pass. The General had spent time in the area before the war, and he was well aware of how well the rugged terrain lent itself to a defender. Instead he decided to continue the tactics that had worked so well and flank Johnston out of his Allatoona entrenchments by moving troops to Marietta, Georgia by way of the small town of Dallas.[27]

The Yankee move towards Dallas did not go unnoticed by General Johnston however, and pulling his army out of Allatoona, he moved quickly to intercept. The Rebels won the race, and when the Federals arrived they found the Confederates drawn up in line of battle along a wooded ridge that ran from Dallas north to a chapel known as New Hope Church.[28]

On May 25th the lead element of the Army of the Cumberland, the 20th Corps commanded by Major General Joseph Hooker, struck the Confederate line near New Hope Church. After a very bloody fight, the Federals pulled back with nothing to show for their heavy losses.[29] While the fighting raged around New Hope Church, the 89th Illinois struggled along with the rest of their corps to reach the front lines, marching on what Colonel Hotchkiss called “blind roads and over a broken country.”[30]

The 89th Illinois took up a position with their division on the Union left on May 26, and spent the day skirmishing and building earthworks.[31] That night Sherman sent General Howard orders to attack the Confederate right flank north of New Hope Church – a fateful set of orders that led to the deaths of many good men in Capron’s regiment.[32]

Howard chose for the attack the 89th’s Division, commanded by Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood. To avoid the excessive casualties that a frontal assault was sure to bring, Howard ordered Wood to march his division around the Confederate right and attack the exposed flank where the Rebels were not protected by entrenchments.[33]

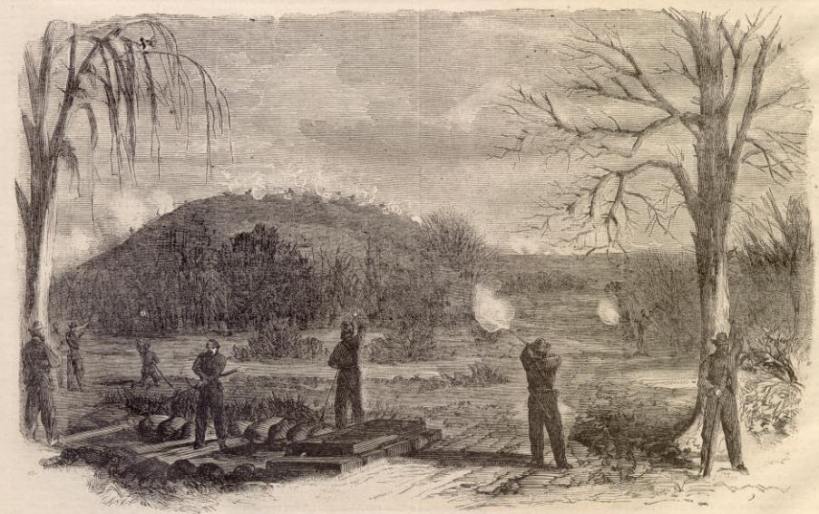

About 1:00 p.m. Capron shouldered his musket as the 89th marched off in search of the enemy flank. The journey took them over broken, heavily forested terrain for two and a half miles, ending up at a place known as Pickett’s Mill.[34] As the Federals moved into attack position, instead of the open flank they were expecting, they saw Confederate soldiers hard at work building earthworks.[35] Even so, General Howard believed the attack could succeed as the Rebel works were incomplete, and at 4:30 p.m. he ordered the attack to begin, but instead of a powerful thrust by his entire division, only the leading brigade, commanded by Brigadier General William B. Hazen, was sent forward. Capron and the rest of Willich’s Brigade, next in line after Hazen, could only watch as their comrades marched off towards the enemy works.[36]

Hazen’s men marched through a thick tangle of forest, pushing back the enemy skirmishers to their main line, a broken, timber covered ridge overlooking a ravine through which the Yankees must pass to reach the Rebel line.[37] As they advanced through the woods the Federals were hit by what the Lieutenant Colonel of the 49th Ohio Infantry called “a desolating fire of musketry and artillery at close range.”[38] The stubborn men in blue pushed to within 20 to 30 yards of the Confederate line before they were forced to take cover from the wall of lead and iron being thrown at them. After enduring this galling fire for 40 minutes, with the brigade running low on ammunition and facing a Rebel threat to both flanks, Hazen ordered his command to retreat.[39]

About the time Hazen’s retreat began, the 89th fell in and prepared to advance – their brigade had finally been given the order to attack. The regiment swarmed over the ground well marked by the dead and dying of Hazen’s Brigade, and soon their own casualties joined them as their ranks were rocked by the same terrible fire that devastated their comrades. Lieutenant Colonel William D. Williams said the 89th advanced to within 25 yards of the Rebel works where “the fire was so murderous that the column paused, wavered, and sought such shelter as they could find.”[40]

The 89th endured the firestorm for an hour when Colonel Gibson ordered the brigade to retreat, but owing to the intensity of the iron and lead being thrown at them, the survivors had to wait until darkness to safely withdraw.[41] The stragglers of the brigade that lingered too long had to run for their lives when the Rebels mounted a nighttime charge to clear the ravine in their front of Yankees.[42]

Among the fortunate few in the 89th Illinois who escaped injury at Pickett’s Mill was Private Charles Capron, but many in his regiment were not so lucky. The unit had 24 killed, 102 wounded, and 28 missing – their worst loss of the entire war.[43]

With the dawn of day the horrific cost of the Federal attack was revealed to the soldiers of both sides. One Rebel in the 45th Mississippi Infantry who surveyed the scene wrote in his diary, “I never saw so many dead Yanks here as I saw in front of Granbury’s Brig. today. It looked as if a line of battle had fallen there, it was terrible to look at.”[44]

In the wake of their ordeal on the 27th, Capron and the rest of the regiment began digging entrenchments, and the men spent the next nine days manning the fortifications. Other than pushing their works closer to the enemy on the 30th, very little of note took place, giving the regiment a chance to recover from the shock of their losses.[45]

Charles knew that his family must have heard about the slaughter at Pickett’s Mill, and concerned they might fear the worst, he penned his family a letter from the trenches to inform them he had survived:

Altona Mountains, May 30th 1864

Dear mother I now seat myself to write you a few lines to let you know how I am for I know how anxious you are to hear from me especially if you got the news that the 89 was all cut to pieces but thanks to the all mercyfull I am still alive and well I will now tell you what kind of a scrape the third division got into.

May 27 we had been marching around in thick timber till nearly noon when we stoped to rest awhile. but about 11 o clock we started again marching to the left suddenly a brisk fire was heard from our skirmishers and well we knew that the first brigade would soon be in action[46] but had no idea off it being so hot a place but we soon found it out for it was not many minutes as we advanced before the bullets that came pattering around us told us that the enemy was near we came to the top of a little hill we found ourselfs in it for earnest we then charged across a little ravine and up another hill to within three rods of their breastworks when we could go no farther we was then reinforced by the 15 Ohio who came up and tried to storm their works but was compelled to fall back we had lost already 3 killed and 9 wounded in our company by dark. at dark the regiments all withdrew but ours we then put out sentinels when their whole line arose about 3 rods from us doubtless thinking that we was a going to charge them they remained in that position about five minutes when their bugle sounded no one knowing what it meant as we are unused to their call but they soon advanced within bayonet reach when our men halted them they halted when a rebel officer steped out of the ranks and fired a revolver twice they then set up a yell and fired a volley into us a good many of our men had no ammunition and then came on the masacre and all our men could do was to get out of their way. I immediately fired my gun knocking a rebel endways and comenced the race they firing a volley after me but I got out all right they catched one of our seargants one fellow held him while the other one struck him he let on like he was one of their own men by exclaiming what in h—l you hitting your own men for they let him go then and he got away in the dark our total loss in killed wounded and missing is 145 the brigade loseing 700 men and the division about 1600.[47]

I will now close by saying that this finds myself and Mr. Copeland well we both send our best respects to all at home so farewell for this time from your affectionate son CC to MSC

tell some of the young ladies to write to me so to pass off time[48]

Memories of this battle stuck with Capron, and even the passage of time and participation in many battles afterwards could not erase thoughts of Pickett’s Mill. Many months later he shared with his mother one of his experiences from the battle:

…we was obliged to lie down for if we had attempted to gone back the balance of us would been shot down. However we laid there and on rushed our support to help us consisting of the 15 and 49 Ohio they came up to where we was laying I was lying behind a log when they came up the officers urged them to go on the line steped up on to the log to git over when six of them was shot down falling onto me and litteraly covering me with blood…[49]

With the lack of a decisive result from the fighting around New Hope Church, Sherman decided to move around the Confederate right flank, sending his cavalry to take possession of the towns of Allatoona and Acworth.[50] The Union Infantry began moving at the same time, starting on the far right of the Federal line, and it was not until June 6 that the 89th Illinois with the rest of the 4th Corps shouldered their rifles and marched east to within two miles of Acworth.[51]

The Federal move did not go unnoticed by the Rebels, and Johnston responded by pulling out of the New Hope Church defenses on the night of June 4 and marching east and putting his army into a blocking position to the northeast of Marietta Georgia, with his left anchored on Lost Mountain, his center on Pine Mountain, and his right on Brush Mountain.[52]

The 89thIllinois had been in their earthworks since the assault at Pickett’s Mill, and the move on June 6 came as a welcome relief from the monotony of the trenches. In a letter written the day they marched out, Capron told his mother,

“We had a pretty hard time of it as there was ten days that we was not alowed to take of[f] our catridge boxes night or day and but one night that we did not have to git out and stand to arms but the Lord is good and thus spared me…[53]

For the next three days Sherman paused his armies to build up supplies, and the 89th took advantage of the respite to rest before the pursuit continued. The advance resumed on June 10, and the 4th Corps made contact with the enemy near Pine Mountain. [54] The 89th Illinois next engaged the Rebels on June 14, when their brigade moved forward as part of a general advance. The Confederates were driven back and the Federals pushed forward three-fourths of a mile until they came within sight of the main line of Rebel entrenchments.[55]

Due to the mounting Union pressure being put on his line, Johnston withdrew his forces from Pine Mountain the night of June 14-15 and pulled back his center to the next fortified line on Kennesaw Mountain.[56] Soon after, with his flanks in danger, Johnston pulled his troops from Lost and Brush Mountains on the night of June 17-18.[57]

As the 4th Corps pursued the Rebels south towards Kennesaw, the 89th Illinois followed a familiar routine whenever they met any resistance: throw out skirmishers, advance and drive the enemy back. This process was repeated time and time again during the Atlanta campaign.[58] Capron was under fire often during the almost daily skirmishing, and being ready for combat at a moment’s notice became second nature to him. In one letter to his brother he casually wrote, “I got your letter all safe and sound the rebels made a charge on us while I was reading your letter had to jump up in a hurry but it did not amount to anything…”[59]

The 89th Illinois particularly distinguished themselves in a skirmish on June 17, charging across 200 yards of open ground to seize some enemy rifle pits and capturing a number of prisoners in the process.[60] Lieutenant Colonel William D. Williams wrote with justifiable pride, “This skirmish was a very gallant and spirited affair, and particularly honorable to the dash and spirit of the Eighty-Ninth Illinois.”[61]

After many sharp clashes, Sherman had his men in front of the formidable Confederate position on Kennesaw Mountain. Up to this point, Sherman had successfully flanked Johnston out of strong defenses, but this time supply concerns, heavy rains, and fear of a Confederate attack made a flanking movement impossible, so he decided to attack the entrenched Rebels head on.[62]

Parts of two Union armies struck the Kennesaw line on June 27, a corps from the Army of Tennessee hitting the right center of the Confederate line, and two divisions from the Army of the Cumberland attacking the Rebel center.[63] For once, the 89th Illinois had some luck – their division was held in reserve and did not have to make the assault.[64] This was indeed fortunate as the Rebel defenders threw out a withering fire, inflicting heavy casualties on their blue-clad opponents. The Union attack failed completely, and at the end of the day all Sherman had to show for his efforts was 3000 killed or wounded men.[65]

Since they were held in reserve during the battle, Capron took the opportunity to write a letter home:

Camp Near Marietta June 27th 1864

Dear Mother I now seat myself to answer your kind letter. I was glad to hear that you was all well as usual these few lines find me in midling good health but nearly worn out as there has not been a day since the 5th of May but what I have heard either the booming of cannon or the rattle of musketry. Have been in 3 or 4 different engagements since this campaign and thankfull I am to almighty God for preserving my live thus far. I can not enter into all the particulars for it would fill to or three sheets of paper. We charged on the enemy the 21 of June and gained our present position and throwed up works under a heavy fire I was on the skirmish line at the time and fired one hundred and thirty rounds my gun got so hot that I could scarcely hold my hand on it. I have been on the skirmish line every other day since I will now finish my letter which I was obliged to postpone a while on account of a fierce artillery duel we came out best a we silenced the rebel battery. We get enough to eat at present and quite a variety we have coffee hardtack and meat for breakfast, hardtack coffee and meat for dinner and meat hardtack and coffee for supper. Mr Copeland is well as usual yesterday our men and the rebels agreed not to fire on one another so we had a pretty quiet day but we was ordered to commence hostilities again this morning had one man killed to day the rebels have got a strong position here and well fortified and old sherman is trying to get around them and oblige them to surrender but it is hard to for old Jonston is a wily foe to deal with. I have not had a letter from Annette for nearly a month she does not write very often no how you said that John Rockwood was in the 112 I want to know what state it is from. You should see the timber that we have been skirmishing in for the last few days there is scarcely a tree but what has from 50 to a hundred bullets in it trees a foot and a half thick has been cut down by our cannon the rebels know how to use their artillery for they put a solid shot into one of our portholes it struck the end of our cannon glanced and struck one of the wheels smashing it up in general.

Most of the boys think the war will close this summer I can think of nothing more to write at present so I will have to quit for this time by asking you to write as soon as you get this tell arthur to write to. If I should get killed remember the government owes me 75 dollars bounty besides six months pay so fareyouwell for this time this from your affectionate Son C. C. to M. S. C.[66]

After the brutal repulse of his men at Kennesaw Mountain, Sherman was not eager for more direct assaults on fortified positions. With the weather improving, he decided to continue with what worked and flank Johnston out of his defenses whenever possible.[67]

Thereafter events moved quickly for Capron as the 89th Illinois took part in a series of flanking maneuvers that brought them to the outskirts of Atlanta. On the night of July 2, Johnston was forced to abandon Kennesaw Mountain because of the threat to his flanks and retreat to a new position with his back to the Chattahoochee River. Sherman again moved around his flanks, and on July 9 the Rebels retreated across the Chattahoochee and took up a new line of defense behind Peachtree Creek.[68]

In a letter written on July 20, Capron explained to his mother how they flanked the Rebels from their Chattahoochee defenses:

…we came to them again just this side of the river but getting one of our batteries in position we give them such a shelling that many of them swam the river they then took up their position on the opposite bank and then how are you yankee. there we was obliged to stop they on one side and we on the other of the Chattahootchie the way our men generally cross is to shell them and swing a pontoon but the rebels has learned this trick so old Sherman quietly sent a corps up the river and then lit into them where we was and they thought we was trying to cross and while we was keeping them in our front the corps up the river quietly crossed now the whole army is all across and within 4 miles of the doomed city.[69]

In the end, his failure to check the advance of the Union armies on Atlanta spelled the end

of Joseph Johnston’s command of the Army of Tennessee. President Jefferson Davis relieved Johnston on July 17, fearing he intended to retreat and abandon Atlanta without a fight. Davis wanted someone to attack the Yankees, and so he promoted John Bell Hood, a man known for his aggressive style of fighting, to full General and command of the Army of Tennessee.[70]

The same day Davis sacked Johnston, Sherman had his armies on the move: Schofield marching on Atlanta from the north, McPherson from the east, and Thomas from the northwest heading directly for the Peachtree Creek defenses.[71]

The Army of the Cumberland began crossing Peachtree Creek on July 20, and Hood wasted no time proving he would fight. At 4:00 p.m. two corps of the Rebel army slammed into the Federals, but they were already safely across the river. The fighting was desperate, but in the end the Confederates were repulsed with heavy losses, over 3000 men killed, wounded, or missing.[72]

The 89th Illinois had been very fortunate in this attack – their brigade was spread very thin to cover an extended line, so thin the brigade had every unit at the front with no reserves held back. But the Confederate attack fell to the brigade’s right, so the 89th Illinois was never engaged in the battle.[73]

After his defeat at Peachtree Creek, Hood pulled back into the Atlanta defenses. Sherman ordered his armies to pursue, but Hood was not prepared to let the Federals invest the city without another fight. McPherson’s troops were advancing on the city from the east, and Hood sent a corps under Lieutenant General William J. Hardee out of the entrenchments that attacked the Yankee flank on July 22. The Confederate attack was repulsed with heavy losses, but it did have one positive result for the Rebels: General McPherson was killed in what came to be known as the Battle of Atlanta.[74]

The next day the Army of the Cumberland made contact with the Rebel entrenchments in the suburbs north of Atlanta. As they had done so many times before, the 89th Illinois began throwing up earthworks to protect themselves. The men came to know these fortifications very well as they were home to the regiment for more than a month.[75]

Trench warfare at Atlanta was a grueling experience for Capron and his comrades as they were exposed to burning heat, rain and mud, and the ever-present threat of Rebel iron and lead. In a letter written from the trenches, Capron spelled out the dangers of life on the front line:

Camp Behind Breastworks

Two miles from Atalanta

July 29th/1864

To the absent ones at home

I now seat myself amidst flying shot and shell for the purpose of answering your kind letter which I just received was glad to hear from you and more so to hear that you was all well this finds me enjoying good good health we are working toward Atalanta slowly this morning we advanced within 3 hundred yards of their fort when zip zip comes the bullets which makes us git down rather low till they got done fireing when we up and give them a volley that made them hunt their holes in a hurry we was then relieved from the skirmish line and came back to camp when they commenced shelling us one burst in the quarters the pieces flying in every direction one piece hit one of company G men tearing the skin from his foot and bruising him considerable in fact there is not a day goes round but what we have some one hurt the weather is very warm here indeed we have occasional showers last night we took 7 prisinors we took to headquarters and the guns I took and fired at the rebels and then broke them over a stump I do not know how long it will take to get Atalanta I hope not long at any rate for I am out of paper envelopes and every thing else they talk of getting our muster rolls made out here and then sent to Nashville and have them chashed if so I shall let the whole of mine go home it will be something over $80.00 dollars and then I want you to send me some of it as I need it and such small articles as I can not get here you need not fear of Lee getting between grant and washington he has sent a small raiding party there to make grant release his hold from Richmond but I do not think he will make out for grant is to sharp for him our men throw shells into Atalanta every day I can think of nothing to write at present Mr Copeland is well as usual and writes every chance he has you must excuse all mistakes and bad writing for I have to dodge the bullets nearly all the time

so no more for this time

from your affectionate

Son C Capron

To the family in general

I will send you some verses that I got out of a rebel letter and a

rebellious stamp[76]

After the Battle of Atlanta, Sherman formulated a new plan to end the stalemate and take the city. He ordered the Army of Tennessee, now commanded by Oliver O. Howard, to march from their camps east of the city to the vicinity of Ezra Church, west of the metropolis. From there they would be in a position to cut the Macon & Western Railroad, Hood’s lifeline supplying his army in Atlanta. Hood, aware of the Federal move, began moving forces into position to attack Howard’s column. On July 28 four Rebel divisions attacked the Yankees at Ezra Church, but the attack was repulsed with heavy losses – the Rebels had over 3,000 men killed, wounded, or missing.[77]

While the fighting at Ezra Church was raging, back in their trenches the men of the 89th Illinois were settling in for a long, drawn-out fight. On August 2 Capron wrote his mother, “…the belief that Atalanta is taken is entirely humbug the city is not yet taken but will stand a siege.”[78] While he didn’t think the siege would end soon, he did note that it was having a negative effect on Confederate morale saying,

…we are wearing them out faster by lying still than any other way for hundreds of deserters come into our lines every day the other night we was on picquet and captured 7 prisinors they say that we wound men in Atalanta with our minie balls distance 2 miles what do you think of that…[79]

From July 23 to August 25, the 89th Illinois slowly advanced their earthworks, eventually pushing their line to within 400 yards of the enemy. While they were constantly under fire, the men were well protected by their fortifications and casualties were low during this period, only 3 killed, 21 wounded, and 1 missing.[80] On August 20th Capron wrote a letter home giving a vivid description of life on the picket line:

in the old place

Camp of the 89

Aug 20th 1864

Dear parents brothers and Sister

Having just received your very kind letter dated Aug 12 I thought that I could not spend my time any better than writing to those I love I should have wrote sooner but old Wheeler got into our rear and tore up the railroad and played smash in generally so there had been no mail in or out[81] however this finds me in good health and hope these few lines will find you all enjoying the same blessing we still remain in the same position go on picquet every third day I went on yesterday and came off this morning in the afternoon yesterday I noticed boxes of amunition coming out on to the skirmish [line] then I knew there would be fun before long and sure enough at five o clock we was all ordered onto the line and then the order was given to open on the jonnies instantly a stream of fire issued from the rifle – pits accompanied by the reports of our rifles which sounded like the heaviest clap of thunder the object was to draw the enemy attentions away while another division charged on the left we had one man killed and one wounded I tell you I had some close calls we had a shower to day which cooled the air considerable I suppose you heard before this time that Mr Copeland was wounded slightly in the knee think he will get home if he does I want him to write to me we get plenty to eat and we are within sight of town I received the comb and cannot thank you any to much for it we have inspection every day and have to keep our guns as bright as silver but this may not interest do not know whether to be glad or sorry for the stranger that you have up there but give it a kiss for me and as for the name I am afraid I would be a poor judge.[82] I was glad to have Arthur write tell him to be a good boy and if I live to get out of this I will come home and see him we expect to be paid be fore long but I have wrote all the news and will quit for this as I have to write Lorain a few lines so good bye for this time I remain your son till death C.C. to M.S.C.[83]

After 34 days of misery in the trenches, the 89th Illinois marched out of their holes in the earth on the night of August 25 – at long last Sherman was moving in force against the Rebels.[84] The General decided to take his entire force save one corps, and move them west around the city and sever the Macon & Western Railroad, forcing the Rebels to come out of their trenches and fight or abandon Atlanta.[85]

On August 31 as the blue columns neared the town of Jonesboro on the Macon & Western Railroad, they were attacked by 24,000 Confederates under Generals William J. Hardee and Stephen D. Lee. The Yankees repulsed the Rebel assault, and the next day staged a counterattack that broke the Confederate line and forced the Rebels to fall back, leaving the railroad to the tender mercies of the Federals. With his only line of supply cut, Hood was forced to withdraw from Atlanta the night of September 1, 1864.[86] The 89th Illinois did not take part in the fighting around Jonesboro as their division was held in reserve and did not reach the battlefield until after dark on September 1.[87]

Sherman pursued Hood to Lovejoy’s Station south of Atlanta, but after due reflection decided not to attack. On September 5 he ordered his armies back to Atlanta to rest and give him time to plan his next move.[88]

The 89th Illinois marched into Atlanta on September 8 with their national and regimental colors snapping in the breeze. It was a proud moment for the regiment, but for Capron there was also a tinge of sadness as he remembered the men who gave their lives on the long march to the city:

…we marched triumphantly through Atlanta with drums beating and colors flying but many was the brave youth that started with us never lived to see the town but they are resting peaceably in a soldiers grave having gave their life freely for their country.[89]

The men of the 89th Illinois went into camp three miles east of Atlanta and finally the regiment was allowed a much needed rest.[90] From May to September the unit had been marching and fighting almost continuously, and the hardships of the campaign had taken a toll on the men. Capron later said of their condition:

…if ever rest was agreeable it was to us poor fellows for we had been exposed to all kinds of weather besides the hard marching under the most intense heat and being up nearly every night more or less (for we was obliged to keep a vigalent watch to prevent a supprise) had tended to wear us out and when we went into camp at Atlanta we had nothing but the best of men the weak and sickly playing out long before.[91]

By the time the Atlanta Campaign ended, Charles Capron had been in the army for just over a year, and he was still a few weeks short of his nineteenth birthday. Although still a teenager, the war had changed a green farm boy into a hardened soldier. Some of the changes were physical, as he explained to his mother:

…you would not know me if you was to see me the change is so great tall and slim and weather beaten enough to be an indian but if you think you can own me I shall be most happy to call round.[92]

The changes to Charles Capron were not only physical – the exposure to the violence and death of the battlefield also changed his outlook on life and made him somewhat cynical. On learning that his father was contemplating buying a farm, he offered the following advice:

You spoke about father going on to a raw farm if he thinks he can make it pay all I have to say is to go ahead and may the Lord prosper him. but whatever he does the best thing for him is to have it in black & white for I have found out since I came to do for myself that it will not do to trust any one for your best friend sometimes proves to be your worst enimy.[93]

Along with his cynicism, Capron had developed a sense of moral ambiguity that at times allowed the worst part of his nature to rise to the surface. A perfect example of this was told in a story Capron related to his mother while he was camped at Huntsville, Alabama:

When we got to Murfreesboro the boys being short of money made up there minds to go through some of the store keepers a niggar tried to hinder us but we wrung his head off quicker than scat but we had arroused the guard and they came to arrest us we told them if they fired a shot we would tear them limb for limb we then sallied on them took away their guns took what we wanted and came away quietly but the 89 was reported [to] Major General Thomas do not think there is much danger of any harm however.[94]

Capron felt no shame for what he and his fellow soldiers had done, and apparently it didn’t bother him to tell his mother about the sorry episode; clearly the war had brought out some harmful character traits in the young man.

The capture of Atlanta ended one campaign, but there was more fighting in store for Charles Capron. The fight at Nashville Tennessee on December 15-16 would be added to his list battles before the bloody year 1864 ended.[95]

With the start of 1865, Capron braced himself for a new season of campaigning, and he made it clear that he was not looking forward to it:

…we will take the train at Huntsville from there to Knoxville and from there to Bulls Gap then we will be where we will hear the roar of the cannon the flash of muskets and the clash of bayonets as we meet in deadly conflict but would to God that I might never see the sight again but I go to my duty and if it comes my lot to fall in the comeing strugle I die content knowing that they is them at home that loves me and will drop a silent tear to my memory. But we will hope for the best.[96]

Fortunately for Capron, the 89th did not see any serious combat in the remaining months of the war. With time on his hands the soldier had time to think about the sacrifices he and thousands like him had made, and he wondered if the civilians at home appreciated how much the boys in blue had suffered. To make sure that they did, Capron took his pen and began to write:

CAMP GREEN

It is late into the night but an unquiet spirit seems to hold sway over mine thoughts, And as I cannot sleep I will write: Elevan O clock and everything is so hushed and still: When compared to the noise and confusion of two hours since Everything seems so deathlike! but a short time ago the air was filled with shouts and laughter the merry notes of the bugler as retreat was sounded or at tattoo when Nellie Bly & Nancy Dawson were receiveing such a murdering at the hands of drum & fife

Now all that I hear to break the monotonous stillness as I sit in my palace of unhewn logs & roof of canvas is the distant notes of a claronette sounding like some boatmans horn in a dream or the quick sharp cry of Halt from some lonely sentinel as he chalenges some intruder upon his precincts. That word halt it causes a start now although I have so long been used to hearing it there is something in the tone acquired from long practise which speaks most forceably to the mind of danger you are strolling around thinking no one near all is still when suddenly halt brings you to a stop with a thrill though you see no one and cannot tell where it came from, yet you half expect to see a tongue of fire from some unseen hand and hear a loud report accompanied by a peculiar whistle which will tell you that the leaden messenger of the pale horse and rider had gone on its mission of destruction. So is a soldiers life bound to obey the commands of a superior officer though in so doing he should hazard the life of a fellow soldier A soldier is a mere machine never supposed to act from his own will yet always yielding obedience to the commands of others no matter how arduous the task he must perform long and tedious marches through every kind of road and weather encamp at night on the ground without shelter cold wet & hungry. or after traveling all day through rain & mud spent a sleepless night on the picquet line watching and warding danger from his fellow soldiers in camp. at early dawn to again shoulder his knapsack & of soldiers friends the truest his musket & perform another long march over roads which were it not war times would be thought impassable for man or beast. O ye who lounge on sofas of crimson dye live upon the fat of the land and never know hardships or sufferings do you, ever cast a thought upon the soldier who volunteers to undergo almost more than human nature can bear that you may enjoy peace & luxury at home among friends and relations. O ye-stay-at-home-rangers how little you know of the life of a soldier ye bread & butter apron strings guards How little is known or realized of what the boys in blue undergo untill one has seen with their own eyes & heard with their own ears. What most precious Set of Blackguards these human beings of Adam will be Who when this war is over cannot boast of having been front and seen the elephant.

C. C.

I sat down and wrote what I thought Charles Capron

You can get this published if you want to[97]

With the surrender of the major Confederate armies in May 1865, Capron eagerly awaited the day the 89th would start for home. He told his mother,

we are laying in camp living fat and greasy waiting for orders to pull up stakes and go home. Home what a thrilling sensation of pleasure steals over me as I think of that simple word simple yet powerful. you must not look for me crossing the threshold for we can not tell much about the military moves sometimes they are quick as flash again as slow as time. Then again what do you take me for a recruit or conscript to think that I cant walk three miles after soldiering 2 years and marching 25 & 30 miles a day for a week on the stretch no sir the first thing you see or hear of me will be in the house and you wont know me either.[98]

Unfortunately for Charles Capron, even though the war was over, he was not going home. He had enlisted for a three-year term, and he still had over a year left to serve, and the government was not about to let him go. When the 89th Illinois Infantry mustered out of service in Nashville on June 10, 1865, the 202 men in the regiment with time left to serve were transferred to the 59th Illinois Infantry.[99] Three days later Capron sadly wrote his mother,

To day I take my pen in hand to inform you of my where abouts. I have been transfered from the 89 to the 59 the old boys has returned home and it is very lonesome here dont know any one in the 59.[100]

Capron’s next letter to his mother contained both good and bad news: the good news was that he was in Illinois; the bad, that the 59th was just making a layover at Cairo before continuing on to their final destination: Texas. Even though it was only a short stay, the soldier was delighted to be back in Illinois:

…down in Texas expect I will roast without a doubt but one thing I got to see Illinois soil again and got some Illinois bread to eat and seen some Illinois ladies at least they claim to be but they looked as so they had been hard run and what is more I dont believe there is a virtuous woman south of the ohio river.[101]

Charles closed his letter with a thought that turned out to be tragically prophetic:

I expect there will be a good many of the troops die off there will be at least if the yellow fever gets among us I do not think there will be any more fighting to do but disease is some times worse than the bullet.[102]

On Independence Day the 59th Illinois boarded the steamboat Nightingale and began the long trip that took them down the Mississippi and out into the Gulf of Mexico. The ship arrived in Matagorda Bay on July 9, and the next day the regiment was transferred to another boat that landed them at Indianola, Texas.[103] The men then began a grueling march in the Texas heat to their campsite, a journey that even the veteran Charles Capron was barely able to complete:

…and then we started for our present camping ground distance 30 miles how shall I ever describe the suffering we endured during the night there was no water on the road and several of the men droped dead in the road I would have given $50 dollars for a glass of cool water I got in sight of the lake and staggered my tongue was parched and swollen and my throat was all on fire by a desperate effort I kept on my legs till I got to the Lake then throwing off my things I just laid down by the lake and drank and kept drinking thought I never tasted any thing so good in my life.[104]

The Texas prairie was a novel experience for Capron, and he wrote his impressions of the strange new land:

Green Lake Texas

July 25. 1865

Ever Remembered Parents

After so long a time it is with pleasure that I seat my self for the purpose of converseing with you a short time. I received the paper you sent me was very glad to get some thing to read have not received any letter for some time am looking for one every day we are still on the plains of Texas enjoying ourselves the best we can which is pretty good living they issued an order for the command to supply itself with milk so we went out and drove in as many cows as we wanted tied up the calves and now the cows come up every night we have a good deal of sport milking them they are wilder than deer and we have to lassoo them. then we have a chance to hunt several of the boys have shot deers since we been here. one of the boys shot an alligator the other morning that measured 12 feet I tell you it was an ugly customor had some alligator soup for dinner one day it tasted first rate and then our company owns a fishing seine go a fishing every day and have all we want to eat of the best kind of fish the weather has been very warm for last two or three days but we had a change last night in the shape of a good rain the first I have seen since I landed on the texas coast it is still raining to day. there is no news of any importance to write and if there was we never would get to hear of it in this godforsaken country we expect to move on to Austin as soon as our supply train comes up which will not be long when we get to Austin I will write again and tell you all what I see and hear what kind of a town Austin is and what kind of folks live there the inhabitants that live round here are about half indian and the other half spanish, I can not understand anything they say. If you want a pony all you have to do is to give them $2.50 to catch one and you have a pony. Well what will I write in fact there is nothing more to write and I will have to close hopeing to hear from you soon from your ever loveing son Charles Capron

To Mrs Mary S. Capron

When this you see think of me

Write soon as you get this[105]

Sadly, this is the last letter that Charles Capron wrote, as less than a month later he was lying in a soldier’s grave. His service record gives the grim report: “Cause of Casualty – Fever – Date of Death – August 22, 1865 – Place of Death – San Antonio, Texas.”[106] Capron, the survivor of some of the conflicts bloodiest battles, died from that great killer of Civil War soldiers, disease.

In 1867 Shepherd and Mary Capron pulled up stakes and headed west to Kansas to make a new start. The couple started a farm, but they were never very successful, and by the early 1880’s the family’s financial situation was so desperate that they were forced to seek a Mother’s Pension based on Charles’ wartime service. In one of their pension applications a neighbor testified:

I first knew Shepard Capron in 1871 that was my first acquaintance the farm he lives on is worth as near as I can judge 500 or 600 dollars. They have not made enough to cover his exemption, 200 dollars. They have not made enough to pay their expenses they are both old and feeble past seventy years, I have always found them both very truthful and honorable the old man is very sick now their income is very limited ever since I knew them they tell me their son that died in the Army was their main support and I believe it. I also believe they are entitled to their pension claim that they are justly entitled to it, as they are both old and feeble.[107]

Mary continued making pension applications until her death on February 22, 1897; afterwards Shepherd began filing claims in his own name. There is no indication in the mass of paperwork that they ever received a dime.[108]

Perhaps the best epitaph for Charles Capron comes from a speech given by Colonel Charles T. Hotchkiss, commander of the 89th Illinois. He said of his regiment, “Our History is written on the head-boards of rudely-made graves from Stone River to Atlanta. Such a record we feel proud of.”[109]

There was one grave even further away than Colonel Hotchkiss realized – a small marble marker in the San Antonio National Cemetery with the simple inscription, “Chas. Capron, Ill.”

[1]

War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 401. Cited hereafter as Official Records.

[2] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 12 February 1865. Charles Capron Collection, OldCourtHouseMuseum, (Vicksburg, MS). Hereafter all letters will be cited as Capron Collection.

[3] For a complete history of Capron’s service during the Chickamauga and Chattanooga Campaigns, see part one, Been Front and Seen the Elephant: The Civil War Letters of Charles Capron, Company A, 89th Illinois Infantry.

[4] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 9 March 1864. Capron Collection.

[5] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 31 March 1864. Capron Collection.

[6] Compiled Service Record of Charles Capron; 89thIllinois Infantry; National Archives, Record Group 94.

[7] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 18 April 1864. Capron Collection.

[8] Castel, Albert. Decision in the West (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1992), 57, 67.

[9] Ibid, 68.

[10] Espositio, Vincent J., ed., The West Point Atlas of American Wars Volume 1 1689-1900 (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959), 145. Cited hereafter as West Point Atlas.

[11] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 401. The 89th Illinois belonged to the Army of the Cumberland, 4th Army Corps, Major General Oliver O. Howard commanding, Third Division, Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood commanding, First Brigade, Brigadier General August Willich commanding. Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 92.

[12] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 12 February 1865. Capron Collection.

[13] West Point Atlas, 145.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 390.

[16] Azron W. Copeland was a Private in Company F, 89th Illinois Infantry. He is mentioned in many of Capron’s letters, and was apparently an old family friend, and possibly a relative. Author unknown, [internet website] Illinois in the Civil War, (Accessed 16 April 2002), http://www.rootsweb.com/~ilcivilw/

[17] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 11 May 1864. Capron Collection.

[18] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 401. Also, Fox, William F. Regimental Losses in the American Civil War 1861-1865. (Albany, NY: Randow Printing Company, 1889), 373. Cited hereafter as Regimental Losses.

[19] Decision in the West, 136-139.

[20] Ibid, 149-150.

[21] Boatner, Mark Mayo III. The Civil War Dictionary (David McKay Company, 1959), 692. Cited hereafter as Civil War Dictionary.

[22] Regimental Losses, 373.

[23] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 391.

[24] Ibid.

[25] West Point Atlas, 145.

[26] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 22 May 1864. Capron Collection.

[27] Sherman, William T. Memoirs of General W. T. Sherman, Volume 2 (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1875), 42-43.

[28] Woodhead, Henry, ed., Echoes of Glory: Illustrated Atlas of the Civil War (Alexandria, Virginia: Time Life Books, 1998), 255. Cited hereafter as Echoes of Glory.

[29] Civil War Dictionary, 219.

[30] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 391.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Decision in the West, 229.

[33] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 377.

[34] Ibid, 392.

[35] Decision in the West, 233-235.

[36] Ibid, 234-236.

[37] Ibid, 237.

[38] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 413.

[39] Ibid, 423.

[40] Ibid, 402.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Decision in the West, 240.

[43] Regimental Losses, 373.

[44] John T. Kern Diary, 28 May 1864. OldCourtHouseMuseum, Vicksburg, MS.

[45] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 403.

[46] Although Capron makes it sound as if the attack took place around 11:00 A. M., it was only the march around the Confederate flank that began at that time. The actual attack took place in the late afternoon. Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 194.

[47] Capron was remarkably accurate in his assessment of casualties. According to the records, the brigade had total casualties of 703 killed, wounded, and missing. The casualties for the division were 1457 killed, wounded, and missing. Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 379, 393.

[48] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 30 May 1864. Capron Collection.

[49] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 12 February 1865. Capron Collection.

[50] Sherman, William T. Memoirs of General W. T. Sherman, Volume 2 (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1875), 46. Cited hereafter as Memoirs.

[51] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 196.

[52] Civil War Dictionary, 452.

[53] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 6 June 1864. Capron Collection.

[54] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 196.

[55] Ibid, 393.

[56] Ibid, 196.

[57] Civil War Dictionary, 452.

[58] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 402-403.

[59] Charles Capron to Arthur Capron, 15 June 1864. Capron Collection.

[60] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 393-394.

[61] Ibid, 403.

[62] West Point Atlas, 146.

[63] Echoes of Glory, 257.

[64] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 199.

[65] Echoes of Glory, 257.

[66] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 27 June 1864. Capron Collection.

[67] Civil War Dictionary, 453.

[68] Ibid, 141, 453.

[69] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 20 July 1864. Capron Collection.

[70] Woodworth, Steven E. Jefferson Davis and His Generals (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1990), 285-286.

[71] Echoes of Glory, 259.

[72] Ibid, 260.

[73] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 396.

[74] West Point Atlas, 147.

[75] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 403.

[76] Charles Capron to the Capron family, 29 July 1864. Capron Collection.

[77] Decision in the West, 424-436.

[78] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 2 August 1864. Capron Collection.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 403.

[81] Major General Joseph Wheeler conducted a cavalry raid on Sherman’s rear with the objective of tearing up the railroad tracks supplying the Union armies. His raid did no lasting damage and was merely an inconvenience to the Federals. Civil War Dictionary, 911.

[82] Capron is referring to the birth of his brother, Bennie Capron, born 1 July 1864. Roger H. Bliss, letter to author, 22 November 2002.

[83] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 20 August 1864. Capron Collection.

[84] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 404.

[85] Memoirs, 102-105.

[86] Echoes of Glory, 269.

[87] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 383-384.

[88] Memoirs, 110.

[89] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 12 February 1865. Capron Collection.

[90] Official Records, Series 1, Volume 38, Part 1, 404.

[91] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 23 January 1865. Capron Collection.

[92] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 25 April 1865. Capron Collection.

[93] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 12 February 1865.

[94] Ibid.

[95] Regimental Losses, 373-374.

[96] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 15 March 1865. Capron Collection.

[97] In some of his other letters Capron gives the location of CampGreen as Huntsville, Alabama. Although this letter is not dated, his other writings from CampGreen are dated between January 16, 1865 – March 15, 1865.

[98] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 14 May 1865. Capron Collection.

[99] Regimental Losses, 373.

[100] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 13 June 1865. Capron Collection.

[101] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 18 June 1865. Capron Collection.

[102] Ibid.

[103] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 11 July 1865. Capron Collection.

[104] Ibid.

[105] Charles Capron to Mary S. Capron, 25 July 1865. Capron Collection.

[106] Compiled Service Record of Charles Capron; 89thIllinois Infantry; National Archives, Record Group 94.

[107] Pension application of Mary S. Capron, affidavit of John Stauffer; United States Pension Rolls. 23 September 1889.

[108] Pension applications of Mary S. Capron and Shepherd Capron; United States Pension Rolls. 1883-1897.

[109] George, Charles B. Forty Years On The Rails (Chicago, IL: R. R. Donnelley & Sons, 1887), 115.